Bordeaux 2024 weather and crop report

Gavin Quinney of Château Bauduc shares his annual, detailed review of the growing season in Bordeaux and looks at how 2024 compares with previous vintages. Above, Cabernet Sauvignon harvest at Château Lafite Rothschild on a sunny October day in 2024.

Here’s my annual report on the amount of wine produced in Bordeaux last year, and how the weather shaped the size of the crop, and the wines, in 2024.

As ever, I’ve put together a formidable series of tables, graphs and maps on both the production statistics and the weather. Some graphics are new, while others have been updated with the data for the new vintage.

The key takeaways are that 2024 is another in a series of small harvests since 2020 – indeed, the smallest crop overall since 1991 – and ‘it was a challenging year in the vineyard but we’re pleasantly surprised by the quality of the wine’.

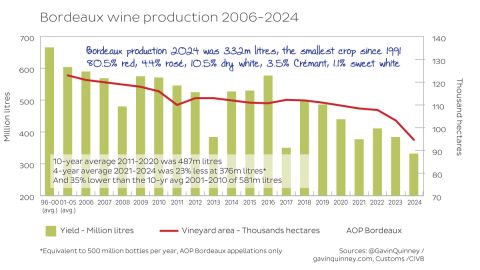

Bordeaux wine production this century

In 2024, Bordeaux produced 80.5% red wine, 4.4% rosé, 10.5% dry white, 3.5% Crémant (most of which was white) and 1.1% sweet white.

After three years in a row of relatively small Bordeaux crops, 2024 came up with even less, with the smallest harvest since 1991.

The 2024 figure of 331.8 million litres, with a yield of 35 hl/ha, followed 2023’s 384 million litres and 37 hl/ha, while 2022 and 2021 saw 411 million litres (38 hl/ha) and 377 million litres (35 hl/ha) respectively.

The four-year average from 2021 to 2024 of 376 million litres is 23% lower than the annual average of 487 million litres of the previous decade (2011–2020).

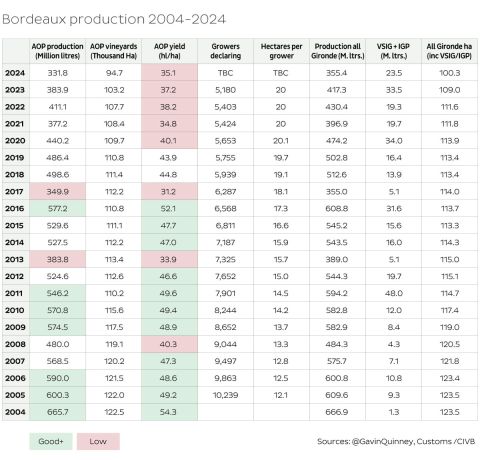

Bordeaux production table, 2004–2024

My table above won’t need to be studied in detail, but it does show how the average yields have dropped considerably in recent years, and that the total area of Bordeaux vineyards is falling too – that’s all the subregions and generic Bordeaux wines that are AOP or Appellation d’Origine Protégée. There’s also a smallish amount (between 4% an 8% each year) of Vin de France and IGP Atlantique (previously Vin de Pays) combined, neither of which say Bordeaux on the label.

In recent years, a combination of frost (2017 and 2021), mildew (2018, 2021, 2023 and 2024), drought and heat (2022), plus hail to a lesser extent (such as in some areas in 2022 and 2024), as well as restrictive yields, regulations, more exacting methods in the vineyard – plus economic hardship to boot – have all contributed to lower production.

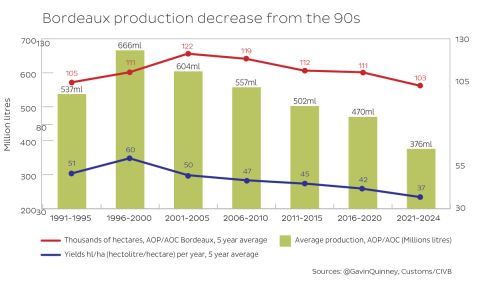

Less wine, land and yields over the years

It is still, of course, a lot of Bordeaux wine. The ‘new’ average of 376 million litres from 2021 to 2024 equates to 500 million bottles per annum and that’s a lot less wine than, say, the 775 million bottles produced on average from 2001 to 2010 (581 million litres per annum). The new levels of production are, however, much closer to the current market demand.

More than half of Bordeaux’s production is sold on the domestic market, which is in decline. In 2024, the USA accounted for 15% of worldwide exports of 200 million bottles and over 20% of the total value (€417 million/€2,045 million). The threat of 25% tariffs is a real concern.

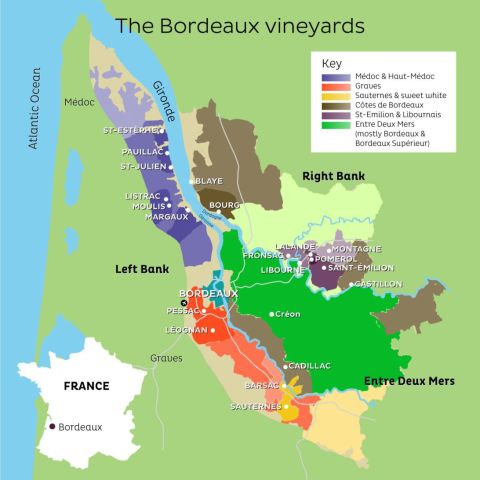

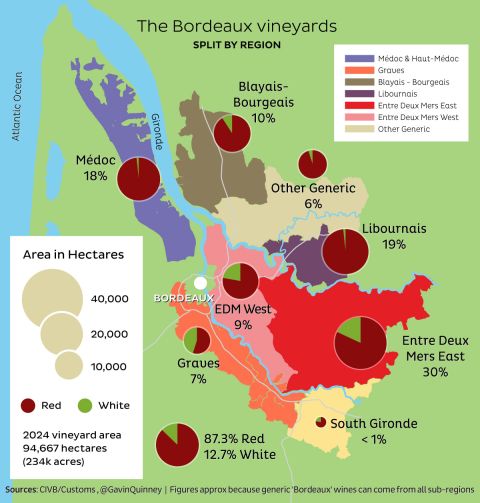

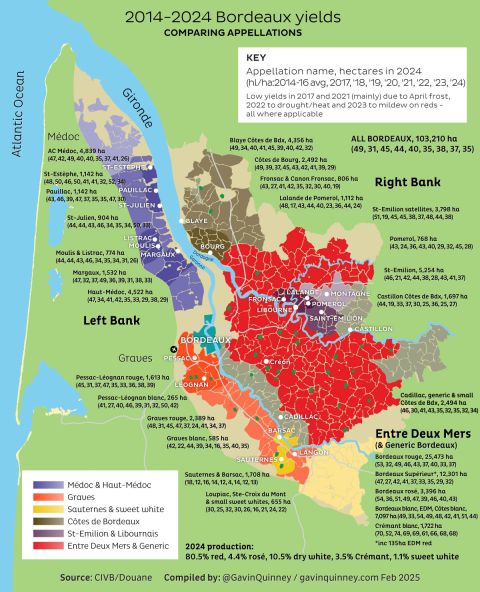

Map of Bordeaux's appellations

A quick reminder of where the Bordeaux vineyards are located before I delve into the production details of the various appellations. It can be useful to see where these places are and what constitutes left and right bank and so on. We live just outside Créon, south-east of the city of Bordeaux, in the Entre-Deux-Mers.

Where all the wine comes from

Here is a breakdown of where all the wine comes from. The Entre-Deux-Mers appellation is better known for its white wine, but an enormous amount of red is produced here using the generic red Bordeaux AOP on the label. The relatively small amount of rosé produced here also comes from red grapes.

Above, St-Émilion in early October 2024. Part of the Libournais subregion – so named after the nearby town of Libourne. (Both Libourne and Créon were founded by the English, incidentally, in 1270 and 1315 respectively.)

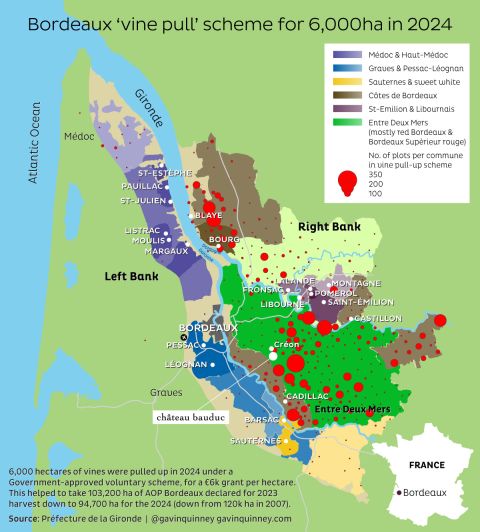

Reducing the size of the vineyard

Sorry, another map, but a lot has been made of the decision to support growers who want to pull up some or all of their vines, and to reduce the amount of red wine being made. Bear in mind that ripping up vineyards has almost nothing to do with the more expensive wines of Bordeaux, so I’ve put this together to show where vines are being pulled out under the grant process.

In addition, there are many growers who are taking out vines outside of the grant scheme, so they retain more control over their land, as there are several restrictions under the grant process. Of great concern are the vineyards that have simply been abandoned because the work of removing vines can be expensive.

There is no doubt that there are far too many red grapevines in Bordeaux, producing inexpensive bulk wine for which there is no longer any market. At Château Bauduc, we don’t need to travel far to see vines being pulled out, as you can see from the map above. A fair guess is that of the 94,700 ha (234,000 acres) declared for the 2024 harvest, at least 30% – by volume – are not financially viable. So this has a long way to go.

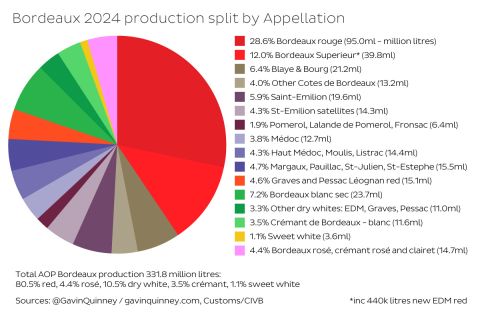

Bordeaux 2024 production by appellation

Over 40% of the wine produced is generic red Bordeaux or Bordeaux Supérieur, plus another 10% or so of Blaye, Bourg and other Côtes. Then there’s a bit more than 10% for St-Émilion and its satellites (Montagne, Lussac and so on) plus 13% from the Médoc appellations, on the left bank, in all. Graves and Pessac-Léognan red, also on the left bank, accounts for less than 5% of the total, and they produce a much smaller amount of dry white (1% – a similar amount to all the sweet white wine produced).

White wine accounts for just 15% of production overall. One area of growth, within the white tally, is sparkling Crémant de Bordeaux. In 2021, 555 ha (1,371 acres) were declared as white Crémant, which produced 4.5 million bottles. In 2024, 1,722 ha (4,255 acres) of white Crémant were declared, making the equivalent of 15.5 million bottles.

Vineyards that are used for Crémant have to be declared in advance because, by law, the grapes are hand-picked for whole-bunch pressing (as at Château Bauduc, pictured above and below). And it’s easy to spot a hand-picked vineyard compared with one harvested by machine as the machines leave the stems on the vine.

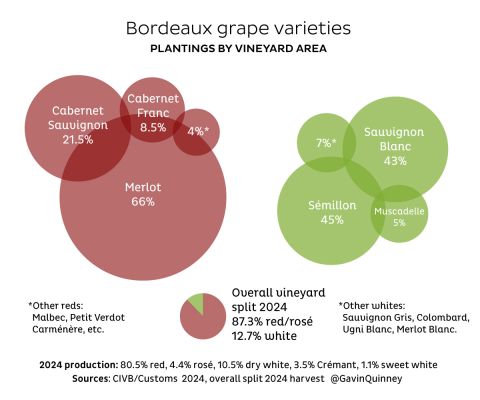

The grape varieties

A reminder of the split of the grape varieties across Bordeaux, which are determined by law within the appellation rules. (Other varieties would either be IGP or Vins de France.)

There is an awful lot of Merlot, from the sublime to the not so sublime. Bordeaux is planted with 87% red, of which two-thirds is Merlot. For whites (13%), Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon are fairly evenly split. New red and white varieties have been added to the list (wow!), but plantings are tiny in volume terms.

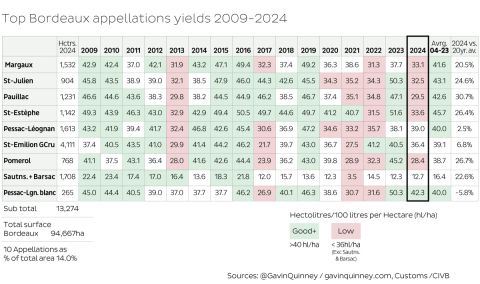

Bordeaux yields 2009–2024 by appellation and wine type

These are the yields per hectare from the whole of Bordeaux, broken down into the main, collective groups. We can see that 2024 produced low yields across the board, with the exception of dry whites and, to a lesser extent, rosé.

What you see most often when comparing yields is how they match up against the previous vintage, which is of limited use. So I’ve taken the yields in 2024 compared with the average of the last 20 years (2004–2023). As you can see, the production per hectare for red wines is down 18–29% in 2024 against that 20-year average.

2013 (poor weather) and 2017 (late April frost) saw low yields, and 2024 is the most recent in a series – for the generic wines – of small crops.

In general, yields for dry white wines from Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillion have been pretty consistent. Ahem, a disclosure – I make far more dry white, Crémant and rosé than Bordeaux Supérieur red these days. Take a look at the Bordeaux Supérieur results of late in the table above.

Yields for the top appellations 2009–2024

It’s a similar story for the more prestigious appellations. 2024 saw low yields from the big four in the Haut-Médoc – Pauillac, St-Julien, St-Estèphe and Margaux – and on the right bank in Pomerol. Yields for these five are between 20% and >30% lower than the 20-year average.

We haven’t seen the average yield in Pauillac being below 30 hl/ha in over 20 years, apart from in 2013 – though the quality in 2024 is better than that difficult year. On the left is the Cabernet Sauvignon harvest at Château Lafite Rothschild on 4 October 2024 and, on the right, sorting the bunches at Château Pichon Baron on 30 September.

To put that figure in perspective, under 3,000 litres a hectare when there are 8,000–10,000 vines per hectare is less than half a bottle per vine (appellations like Pauillac have double the average number of vines per hectare, and generic Bordeaux is often made using 3,000–3,500 vines per hectare.)

It’s worth noting that the comparatively low yields for 2024, 2022 and 2013 (and for 2017 in Pomerol and St-Émilion) result in completely different wines from one vintage to another. But also note that average yields in 2023 were pretty strong in the top appellations compared with the rest of Bordeaux.

The big map of Bordeaux yields 2014–2024

My utterly bonkers map showing the yields in recent vintages across Bordeaux. There are some startling figures for 2024 alone. Who’d be a winegrower? Every year and every appellation – and every grower – has their own story. The low yields (half those of 2023 on average) in Fronsac and Canon-Fronsac on the right bank, for example, were in part down to hail in mid June. Some growers there were lucky, others less so.

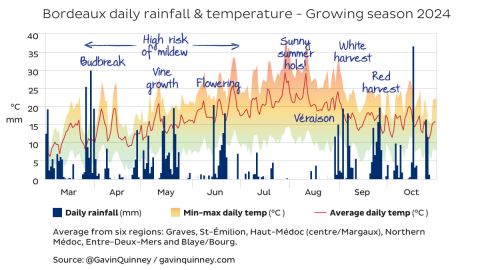

The weather for Bordeaux 2024

And now for the weather. This is a chart I’ve put together each year since the 2016 vintage, taking the data from weather stations in six subregions of Bordeaux – see the maps above – to get a more representative picture of the vintage. Note that there can be significant variations in rainfall from one area of Bordeaux to another at key times.

You can see how the different vintages (2016–2024) compare in a separate post on my website.

The graph shows the average rainfall and temperatures each day during the season. I’ve included March and October for 2024, bookended onto the key six months of the actual growing season from April to September. Heavy rain in March had an impact which I wanted to show, and the ‘high risk of mildew’ in the following quarter was, as with 2023, a huge factor. Some colleagues and I estimate that mildew accounted for about 20–25% of the reduction in yield overall. Poor weather conditions in the first months of the season were also an important consideration.

October is shown because the harvest continued through a rainy September and into October for the reds, and for the sweet whites.

We shall see below how 2024 is considered a rainy vintage, but it shouldn’t take away from the fact that we enjoyed a really good summer from mid July to the last week of August. Great for holiday-makers, and the sunshine certainly improved the quality of the wines.

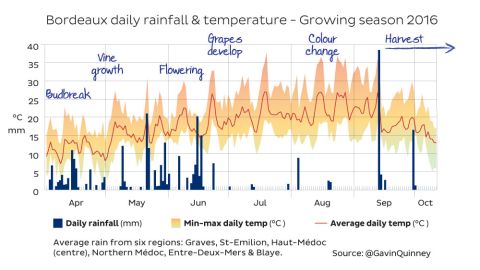

I’ve included the 2016 chart here as a comparison because that was a great all-round vintage for Bordeaux, with high yields, too. Fine margins, really. Nothing wrong with spring rain, just not too much (as in 2024). A dry summer is most welcome – but not too hot – and a good dollop of rain to freshen up the (red) vines before the harvest a couple of weeks later.

The purpose of this chart is to show the total rain and average temperatures for each week and to compare the monthly figure for 2024 versus the 30-year average for Bordeaux. It throws up the odd anomaly, such as August showing that we had 34 mm (1.3 in) of rain that month, but most of that came in the last week (and therefore shows in the first weekly bar in September). When you’re harvesting white grapes at the end of August and the start of September, you remember those details.

The summer apart, we had quite a lot of rain, as we shall see. Overall, there were fewer bunches and loss of yield through poor fruit set resulting in coulure and millerandage. Coulure is where there are gaps in the bunches because fewer grapes (or berries) were formed at all – Merlot is particularly susceptible to this during flowering – while millerandage is where some berries are malformed and remain tiny.

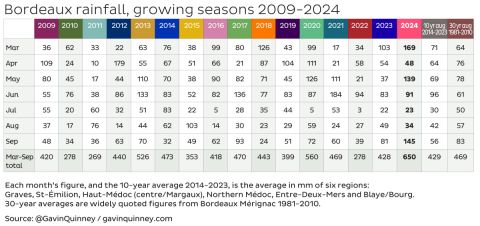

Once again, I’ve been using the data from the six weather stations across Bordeaux for these figures. I’ve kept 2009 and 2010 in this widening table as they were both great vintages with varying statistics. As you can see, we had more rain in 2024 for the period of March to September than in any of the previous vintages shown here. Of course, May and September – both important months – were wet.

It’s also quite instructive to see how much rain we had at other times and there’s no doubt that the amount of rain we saw in the winter, before the growing season, had a significant impact on the vineyards. And every grower’s ability to treat the vines. The high total May–September figure – a key period – was comparable to 2021 but with a different pattern. The September average – during the harvest – was especially high for 2024.

The table is also handy to see how things are evolving over 5-, 10- and 30-year spreads. June is getting wetter – often down to storms – while July is becoming drier.

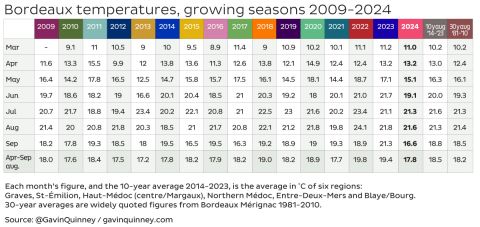

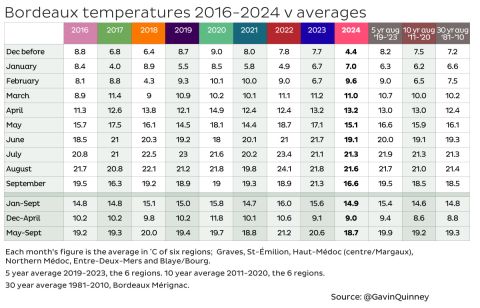

Here are the temperature statistics for the same vintages. May was cooler in 2024, as was September – considerably so during the harvest. I've taken the April to September averages as those are the main months of the growing season. What this table doesn't show is the amount of sunshine, and less sunshine at key times in 2024 had a major impact. A chart for the future, if it's possible.

As with the rainfall, I’ve updated the figures for temperature averages from across the region.

Finally, how the vintages compare

One for wine geeks, but I like this graphic showing how the different vintages compare – based on the temperature and rainfall statistics from February to September each year (Bordeaux Merignac data). In the hot and dry quadrant, unsurprisingly, we find 2022 and 2003. 2024 was wet but, mercifully, not too cold (where we find the unwanted 1992).

The tastings of the new 2024s by the trade and the wine press begin later this month. Meanwhile, for us, it's back to the new labels – QR codes for ingredients (grapes) and all that – for our freshly bottled whites and rosé.

Onwards and upwards.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,423 featured articles

- 273,870 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,423 featured articles

- 273,870 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes