Slovenia's green-black gold

Pumpkin-seed oil as complex, terroir-reflective and delicious as great wine.

The smell was rich in the air. Sweet, roasted, green, nutty, toasty. The landscape was flat, arable, no grapevines here. We squinted in the sunlight, were greeted by a slim, handsomely athletic and immaculately tattooed, blue-eyed man wearing a tight black T-shirt and a wide smile. We walked through a tall, broad, brand-new wooden door into a Scandi-sparse, very smart, very clean room.

The night before, I’d confessed to one of Slovenia’s top winemakers, Uroš Valcl of Marof, that I loved Slovenian pumpkin-seed oil so much that all my previous trips to Slovenia had resulted in a suitcase loaded with bottles of bučno olje* (pumpkin-seed oil) rather than the usual motherload of wine that I come home with. I’d tried buying pumpkin-seed oil in the UK but was always disappointed – the flavour was nothing like bučno olje. Why? He replied, ‘Vredu [ok], jutri [tomorrow] we meet with Gorazd.’ The tattooed man was Gorazd, the owner of Kócbek, one of the finest artisan pumpkin-seed oil producers in the world.

Although pumpkin-seed oil from Styrian Austria might be better known, the Štajerska and Prekmurje regions of eastern Slovenia have a history of pumpkin-seed oil production that goes back to the mid 18th century. The oil from these regions is so distinctive and has such a long pedigree that in 2012 the EU granted ‘Štajersko prekmursko bučno olje’ PGI status, strictly regulating production and labelling.

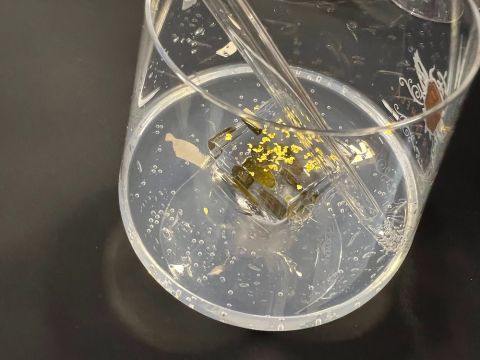

There are 825 varieties of pumpkin/squash (Cucurbita pepo) around the world, but only one variety is used for oil: the Cucurbita pepo var. styriaca. It’s a yellow-and-green stripy pumpkin, somewhere between a handball and a basketball in size. In Slovenia, it’s planted in the rich, clay-based valley soils of the eastern part of the country in April and is harvested, usually by machine, around August or September. The flesh can be eaten, although it’s not particularly flavourful; once the seeds have been extracted, the rest of the pumpkin is usually spat back out into the field by the harvesting machine and is either ploughed back in as natural fertiliser or fed to pigs. What makes this variety so special is its large, fat, dark-green seeds, called golica (gol-eetsa) – they are naturally husk-free and are particularly high in fat, vitamins and minerals. As an interesting aside, and to demonstrate the impact of terroir on pumpkin-seed oil, Gorazd showed us a jar of golica from one of their local farmers and a jar of seeds that had been grown in China (where a much cheaper pumpkin-seed oil is produced). Despite coming from the same variety of styriaca pumpkin, the Chinese seeds were markedly smaller and lighter in colour. They produce a lightweight, light-flavoured, nutritionally neutral oil.

The Kócbek oil mill was established in 1929 by Alojz Kocbek, Gorazd’s grandfather. In the beginning, local families, farmers and restaurants brought their own seeds to the mill, paid to have them pressed, and then went home with a few bottles for personal consumption or to sell at the market or to customers. Nowadays, Kócbek works with 30 to 40 farmers within a 45-km (30-mile) radius who grow pumpkins specifically for Kócbek to their pretty exacting standards. They bottle a range of oils under the Kócbek brand, but they also make oils for other brands and on behalf of private customers. They also happen to make the most expensive pumpkin-seed oil in the world – a stone-pressed, organic oil from selected seeds which retails at €450 for 250 ml. Add in a solid gold label and a hand-made oak storage case and you’re looking at over €1,200. The bottle is hand-blown black glass and refillable, mind.

Apart from variety, climate and soil, there are other critical factors in the production of high-quality pumpkin-seed oil. It’s essential that the seeds are cleaned, perfectly, the same day that they are harvested. If they aren’t, they stick together and cannot be pressed. They then need to be dried immediately to prevent rot. Because of the crucial timing of the cleaning and drying processes these steps are carried out at the source by the farmers. Once the seeds have been cleaned and dried, however, they can be stored for up to five years so that oil can be produced throughout the year. The quality of the seeds is very important – seeds are sorted for high-quality oil to ensure that there are no ‘thin’ or husked seeds. How the oil is made is also critical. Gentle and slow.

The Kócbek mill has been pressing oil six days a week, every week of the year bar public holidays and one or two emergencies since they began in 1929. The process hasn’t changed. In fact, even the equipment is exactly the same. Gorazd’s grandfather bought his milling machines, roasting oven and presses second-hand in 1929. All of them are, to this day, making the oil that comes out of Kócbek. I watched them in action myself.

It’s a mesmerising process, not least because of the heady aroma of roasting and crushing seeds. But there is also a sense of timelessness, a gentle hum, a slow rhythm to each process, happening concurrently in the tiny and surprisingly beautiful Kócbek production room. There are domestic kitchens that are bigger than the happening heart of Kócbek (even their shop is bigger!). The walls are lined with beautifully intricate, black-and-white patterned traditional Slovene tiles. To the left, as you walk in, is the ATM-sized 19th-century iron mill with a hopper at the top. The miller walks up wooden steps in the adjacent room to a little platform, opens a door, hefts a sack of seeds to his shoulder and pours them in from above. While the seeds are being crushed to a green-gold-black mash, the previous batch of mash is being slowly churned in an equally ancient, but perfectly functioning mixer, to thoroughly mix it with water.

I was a bit perplexed as to why the mash had to be mixed with water, but Gorazd explained that this was an essential step: once the seed mash goes into the roasting pans (set into an ancient, beautifully tiled ‘stove’) and the slow roasting process begins, the water protects the seeds from being burnt until the oils are released; thereafter the oils protect the seeds. Kócbek roast at the lowest possible temperature (100–110 °C/212–230 °F) to preserve aromas, minerals and vitamins. For comparison, he says, Austrian pumpkin-seed oil is usually roasted much hotter, up to 200 °C (392 °F), which results in a much darker, thicker oil with more aggressive texture (it can be quite ‘burning’, we’re told).

From here the still-warm, giddily fragrant seed mash is hand-spooned into a vintage press not much bigger than a chimney pot. Layers of mash are interleaved with steel plates to ensure that the pressure is evenly distributed and allow the very simple press to extract oil more efficiently without extracting any harshness. The oil, black and silky as it oozes out the press, dark-ruby red in the light, with a luminous green froth, begins to slowly stream from the press into small buckets. Pumpkin-seed oil has an unusual optical characteristic called dichromatism: it looks red in concentrated depth or thickness but smear it across a piece of paper or swirl it through cream and it is bright, bright green.

They leave the oil to naturally settle in tanks for at least two weeks to avoid filtration. Bottling is done on site. The whole production process for a single batch takes approximately one hour and 45 minutes, is done by just one person, and produces 17 litres (4.5 gallons) of oil per hour. One litre (a quarter gallon) of oil requires about 3 kg (6.6 lb) of seeds, which equates to approximately 33 pumpkins. So that’s 561 pumpkins an hour. This is concentration. It’s about as hand-crafted and artisan as commercial oil production gets.

It’s also a zero-waste process. The pressing creates thin, circular, dense ‘cakes’ of pressed seeds that are intensely rich and very high in fat (15–20%), proteins (55–60%), minerals and vitamins. These are highly sought after by dairy farmers because the cakes increase milk production and quality – and the cows love them! The pressings are also used to produce pumpkin-seed flour which they sell to local bakeries, and pumpkin-flour salt (which is bright green and deliciously nutty and aromatic). Gorazd tells us that the price of pumpkin-seed flour is going through the roof and will soon be higher than the pumpkin seeds themselves. Demand for the press cakes is ten times higher than every oil mill can produce.

Despite its long history, Kócbek is pioneering and innovative. They were the first in the world to produce cold-press pumpkin-seed oil in 1996. The technology was so new that they had to get permission from the Slovenian ministry of agriculture and the EU to commercialise production. The seeds are not crushed, heated or mixed with water. It takes 6 kg (13 lb) of pumpkin seeds, or 66 pumpkins, to produce one litre of cold-press oil. The rule is that the temperature of the seeds must not go over 40 °C (104 °F), which means a very slow press to avoid high friction generating high temperatures. The result is a light-textured, reddish oil which is much less aromatic and flavourful than its hot-press counterpart but is fruity in flavour (strawberries, sweet hay) and intensely rich in vitamin, mineral and antioxidant compounds.

Working with a local chocolatier, Kócbek were also the first to make chocolate with pumpkin-seed oil (as opposed to pumpkin seeds), which makes a chocolate with quite a low melting point. Their pumpkin-seed gin is also pretty good! Although I may have been swayed by the uber-cool ice cubes …

I’ve grappled with trying to describe the depth, texture and flavour of ‘Štajersko prekmursko bučno olje’. This iridescent, black-red-green-gold, languid elixir is, of course, intensely nutty. But it also tastes of green grass and bay leaves, of strawberries and quince peel, of freshly tossed hay steaming on hot summer fields, of tobacco leaves drying in sheds and toasted coconut. It’s the one oil I could eat, literally, by the spoonful. It’s bright and fresh in flavour, but with a long, sumptuous, roasted-potato-skin buttery richness.

The Slovenes use it on everything. They are a salad-mad nation, and while you might find some salads dressed with olive oil near the coast and the western Brda part of the country, everywhere else, it’s bučno olje. Breakfast, in Slovenia, is sourdough bread with fat slices of home-grown tomatoes, pale-green paprika and skuta, a type of cottage cheese, lavishly drizzled with bučno olje. Or, eggs fried in bučno olje served with Prleška tünka (sometimes spelled šunka – a Slovenian dry-cured, smoked ham stored in lard) – the literal version of Dr Seuss’s green eggs and ham. It’s pretty damn good, especially if you have a little glass of penina (sparkling wine) to hand. (Don’t be shocked – in Slovenia a glass of homemade schnapps with your morning coffee is pretty standard in rural regions …). In terms of wine pairing, the local Zelen is perfect, and so is Šipon (aka Furmint). But any wine with a nutty, green, floral profile (think Verdicchio, Malvazija, Xarel-lo, Soave, Sémillon) would be great.

Talking about fried eggs, it’s interesting to look at the smoke point of this unrefined, highly aromatic, richly flavoured oil. Common wisdom would assume that it’s an oil to dress food with rather than cook with. While the smoke point of refined oils is generally between 190 °C (375 °F) and 250 °C (480 °F), it’s not generally understood that certain unrefined oils actually are quite stable at high temperatures, albeit some holding their structure better than others. The smoke point of unrefined sunflower oil is about 108 °C (226 °F), unrefined olive oil is 120 °C (248 °F). Unrefined Bučno olje has a smoke point of 168 °C (334 °F). This means that, if you heat the pan first without the oil in it, you can flash fry food in bučno olje without damaging its flavour or losing too much of its nutritional richness. Bu the most delicious use of this oil is, by far, drizzled on vanilla ice cream. Sprinkle with roasted, salted bučna semena (pumpkin seeds).

If you want recipe inspiration, have a look at their website. Kócbek will post their oils to pretty much anywhere in the world, I’m told.

*Bučno olje is pronounced boochno oliya

All photos are my own except for the photos of the bowls of skuta (credit Liam Cabot) and of the Styrian pumpkin and the bottled oils (from Kócbek).

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,414 featured articles

- 274,248 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,414 featured articles

- 274,248 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes