The recently announced third lockdown in England brings a new set of challenges for many restaurateurs and chefs. Of them all, the biggest is probably how to reorganise their restaurants to meet demand for takeaway and delivery – to somehow keep their customers happy, to maintain some form of cash flow and to keep their brand name alive. And, above all, how to cope with the ever-changing circumstances.

The timing has certainly changed. Gone are the slightly crazy days of early December when UK restaurants were open and there were plenty of hungry customers. There are still plenty of hungry customers out there – what else is there to do in the evening except to eat and to drink as well as you can? – but the pre-Christmas froth has gone. The gloomier nights of January and February stretch into the immediate distance.

If they choose to ‘pivot’ from serving customers from a carefully planned à la carte menu in the restaurant, where tables, principally of twos and fours, come in at an appointed hour, these same restaurants, with the same kitchens, are being put to a very different use. Kitchens with a layout that has been designed for the transport of food across no more than a few yards now have to supply food that involves a journey out of the front door, into a waiting vehicle, and then perhaps several miles of a bumpy journey. This is now a fact of restaurant life and it is likely to be like this for the next few months.

The distance food has to travel is a very important consideration in the construction of any restaurant. In my old restaurant, a kitchen in the basement meant that we had to rely on ‘dumb waiters’, and as a result, pasta could never feature on any menu because it congealed by the time it arrived at a table on the third floor.

When London’s Como Metropolitan Hotel opened in 1997, its owner Christina Ong was very keen on a tie-up with the owners of The Wolseley restaurant along Piccadilly. The shape of the proposed restaurant precluded this simply because of its unusual length and it became London’s first Nobu. Plates of cold sushi were not going to be affected by the long distance they had to be carried from the kitchen.

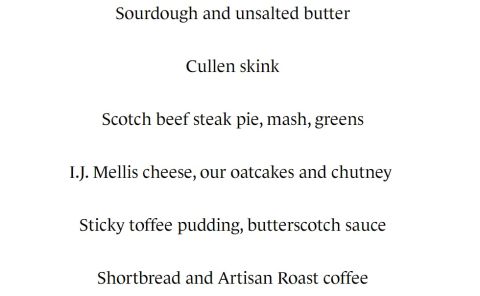

It is these logistical matters, as well as the tie-up with a suitable delivery company, that will now dictate the precise menu any restaurant can offer. One of the first to arrive in my inbox, on Sunday 3 January, came from the elegant Cafe St Honoré in Edinburgh. It read as follows:

This menu, priced at £27.50 per person, has been cleverly tailored by chef/proprietor Neil Forbes, to appeal to his customers at the start of one of the coldest months of the year (it is forecast to be no more than 4 °C in Edinburgh today and not that much warmer next week).

Consequently, there is a soup to start but one whose recipe requires more than just amateurish preparation to get right. Then, as a main course, there is a pie, all ready to heat up, together with a couple of side dishes that require little more. Then there is a cheese course followed by a couple of variations on a sweet finish: a sticky toffee pudding and some Scottish shortbread.

This menu allows the restaurant to exhibit two further attributes. The first is to make the bridge with their customers by offering full details on how to prepare their supper. Preparation instructions, included with every order, is a constant now with every takeaway. So too is the opportunity to brandish their environmental aspirations. The end of the menu reads, ‘in line with our sustainability and environmental philosophies, all packaging is compostable, recyclable or reusable’.

This menu gives a foretaste of that on offer from many other chefs around the UK and anywhere that has thought through the logistical challenges of delivery. A soup is a very clever first course: easy to transport, easy to reheat, and welcoming. It is a dish that can easily be replaced by a well thought-out salad should warmer weather ever arrive here in the northern hemisphere.

So too is the steak pie, the subject of numerous variations, other cuts of meat, fish, vegetarian or vegan. Equally attractive, to chefs and their customers, are ingredients such as a whole chicken that can serve two or more; the last of the game birds; dishes such as osso buco; while the bravest chefs, such as Chris and Jeff Galvin, are even venturing a seared pavé of wild seabass with crushed charlotte potatoes and a raisin and caper dressing. Desserts range from ice creams, delivered frozen in pots, to a Fern Verrow rhubarb and apple crumble from Spring restaurant, to my particular favourite, a Mont Blanc from Clarke’s in W8, delivered if you live within 30 minutes of the restaurant by an eco-friendly bicyclist.

This switch from having to go to the restaurant to having a restaurant’s food delivered has allowed us and our family to experiment. We have all enjoyed some authentic and easy-to-prepare Thai food, delivered from Kin & Deum close to London Bridge. And our next order will be Malaysian: kari laksa, egg noodles in a curry broth with seafood and chicken, followed by pisang goreng, their ultra-sweet banana fritters, both from Roti King, a small basement restaurant near Euston station whose popularity used to be such that I could get in there for lunch only after 2.30 pm.

I will end with the words of Stuart Andrew, the executive chef at Portland and Clipstone restaurants, owned by our son (Clipstone's takeout dinner for last night pictured above; components in italics below). When I asked him what were the biggest challenges for him as a chef pivoting from serving customers in the restaurant to the new normal, his response was typically modest and to the point.

‘The main differences result from having to package the food. This in turn raises issues regarding presentation, preservation (shelf life) and additional labour. It is also worth noting how the customers will engage with the food. It can’t be overly complicated to reheat/cook/construct.

‘During a restaurant service a lot of touches to dishes will be done last minute, sending a relatively small number of dishes at a time, knowing the food will be consumed within minutes. Currently from Portland and Clipstone we will be sending 75 entire meals for two on Friday morning all packed and ready to be delivered. That is the equivalent of 150 covers, the same number as we would normally serve in a couple of days.’

All this presents a series of significant challenges. But these are challenges that I expect more and more chefs will have to rise to in the coming months.

Clipstone dinner last week, pictured clockwise from the top: custard tart with new season's rhubarb; velouté of English squash with toasted seeds and pickled chilli; truffled cauliflower and cheese; cannelloni with slow-roasted lamb shoulder, artichokes, winter tomatoes and pecorino; and the caramelised onion and gruyère brioche that accompanied the soup. (Missing: the sourdough bread with French demi-sel butter, house pickles, crudités and anchovy cream, and beef shin empanadas with ponzu mayonnaise.)