Last week I gave a talk in Barcelona entitled ‘Wine experiences from the greatest menus in the world’.

Towards the end, I moved on to a quiz. I showed the audience photographs of the chefs behind 10 of what I regard to be the world’s finest restaurants. Then I went on to ask one simple question about them all.

So here goes:

Helen Darroze of the Connaught Hotel

Alain Ducasse, of many, many restaurants

Anne Sophie Pic from Restaurant Pic, Valence

Nobu Matsuisha of Nobu

Jose Avillez of Belcanto in Lisbon

Massimo Bottura of Osteria Francescana in Modena

Heston Blumenthal of The Fat Duck in Bray

Rene Redzepi from Noma in Copenhagen

And finally two British chefs:

Michel Roux Jr of Le Gavroche

Fergus Henderson from St John

This is really an international line-up of top chefs from around the world.

Now my question for you, and to the audience in Barcelona, is this: who knows the name of the person who chooses their wine list or, even more profitably for them, their choice of wines by the glass?

To this question no one in the room knew the answer. No one could name even one of these people.

And yet they are the people responsible for most of the bill, particularly given the rise in the price of top bordeaux and burgundy. If they or their team of sommeliers are doing their job properly, they will contribute most of that service’s profitability. Because, to repeat, wine in a great restaurant contributes a bigger proportion of the profit than the food, although the food is invariably the reason we all chose to dine there in the first place.

My first point is this: how does this serious omission come about? There is room on the menu and even above the door, just as there is for the chef’s name, for that of the person who has collated the wine list. It is he, or increasingly she, who is responsible for half the pleasure and possibly over half the bill. And when I am out with Jancis, we certainly feel a strange shimmer of pride when our wine bill is more than the amount we have spent on food.

But then this is probably because I, or we when there are more of us, are with Jancis, and her focus is more on wine than food. I remember that I had terrible trouble getting her on a week’s family holiday to Egypt many years ago simply because she said that she would miss wine too much!

Jancis is, I believe, an atypical restaurant customer and I am currently talking about wine lists in great restaurants which, by definition, have only a certain number of seats and tables in each of them. The world’s great restaurants do tend to be small and are getting smaller. Noma has 40 covers, The Fat Duck had 46 but that is now down to 40, Massimo Bottura’s restaurant is even smaller. Only Nobu’s restaurants do volume and are on a scale that borders on the impersonal. So why are all these chefs reluctant to share the limelight with those who put together their wine lists? In all my years of eating out, I can think of only two instances where the sommeliers were named in the establishment’s literature: at Quay restaurant on Sydney Harbour overlooked by the gigantic cruise liners that berth there; and, I'm delighted to say, at the new Hide restaurant in London, a sister establishment to the luxurious Mayfair wine shop Hedonism that I will be reviewing soon.

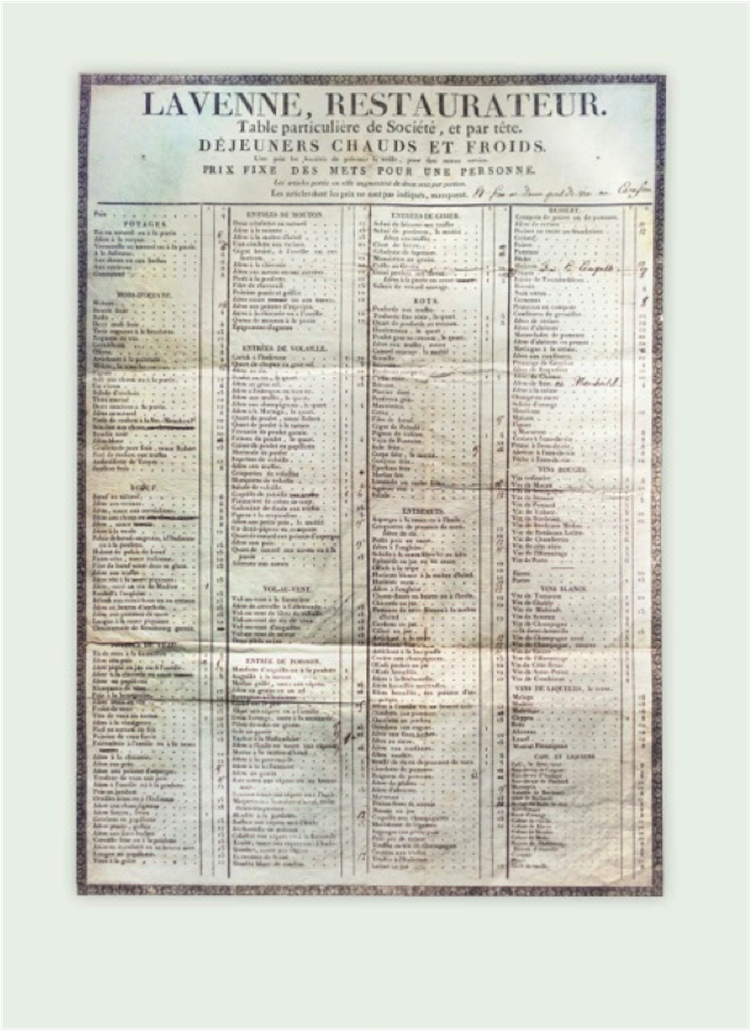

I believe that there are several reasons for this strange omission. Firstly, for historical reasons the name of the restaurateur came first and the wines a distinct second. This seems always to have been the case. Below is a menu from Lavenne in Paris in the early nineteenth century. In those days menus were written on the only means of printing then widely available. These menus look like sheets of a newspaper because that was all that could be printed inexpensively at the time.

Menus in the early nineteenth century were large, single-folio sheets packed with columns of closely printed type, all of which follow a similar layout. The wines are laid out in the bottom right hand corner, here under the headings vins rouges, vins blancs and vins de liqueurs. And in this position wines have consistently remained – a position that is secondary to the food.

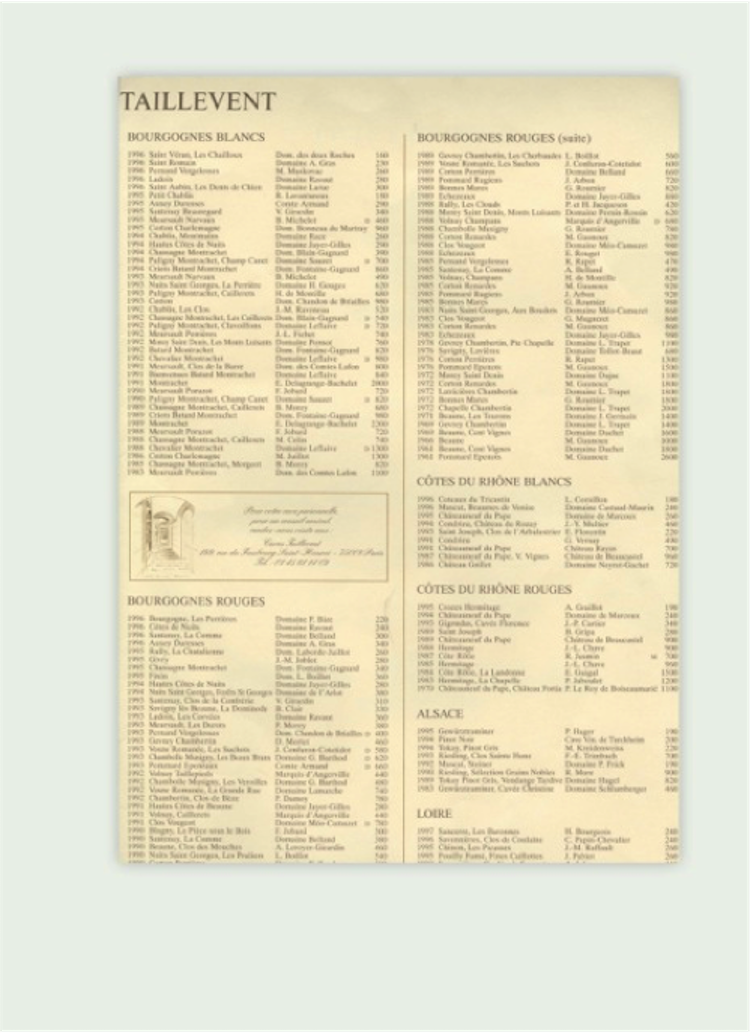

As the sommelier’s role has grown, then so too has the appearance and importance of every restaurant’s wine list. And over the past 70 years they have come in many forms: from the chic tables of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles complete with monkeys and palm trees, to the very colourful wine list at Charlie Bird in New York, to the classic and perhaps never-bettered combination of the menu and the wine list that was given to every diner at Taillevent, the two-star Michelin restaurant in Paris that was named after one of France’s great chefs and coaxed to its three-star prominence by Jean-Claude Vrinat, the son of its founder.

Vrinat, whom I had the great pleasure of knowing as well as any customer of his did, believed that to be a successful restaurateur you had to be in love with three things. In no particular order they were: food, wine and people.

And he designed the perfect wine list and menu to please all his customers. The Taillevent menu was a four-page affair with the first courses and the main courses on page one and the cheese and desserts on page four. Pages two and three (below) were the wine list, although Vrinat was such a prodigious collector that there was not room for all the wines he had to offer. But his principal purpose was achieved: everyone got to look over his wine list at the same time.

This was a very important point for Vrinat as his method avoided the embarrassing question for the restaurateur of initially asking who was the host, the person to whom the wine list is invariably offered. Then it empowered the whole table, which led, as he once told me, to a considerably higher spend on wine than had been anticipated. Everyone could now see whether the host was being mean with his or her wine selection and perhaps chivvy him, or her, along. Finally, there was the empowerment factor – with everyone being given a wine list, no one could claim to be left out of the selection process.

Here, in a very great restaurant – and Taillevent was for many years the only three-star restaurant run by a restaurateur rather than a chef – was the embodiment of what a menu and a wine list should be, how they should be combined to everyone’s advantage.

So here are my two takeaways, two simple changes that I believe will improve the wine experience of customers in great restaurants.

First of all, chefs ought to acknowledge more openly and explicitly the names of the people who write their wine lists.

And the design of the menu and the wine list ought to be improved so that every customer can enjoy both of them simultaneously.

I am making these two points altruistically. I have no interest in writing another book even though it was suggested to me that I follow up my On the Menu with a survey of wine lists. But I sincerely believe in these points and I hope, one day, to see them both enacted. Then we can really begin to enjoy great wine in great restaurants.