Dramatic contrasts between developed and developing worlds on the restaurant floor revealed. This article has been syndicated.

Travelling around the world as I, naughtily, do – trying to offset my carbon emissions but always with my eyes wide open – I am struck by the contrasts between the developing world and the supposedly developed world, Europe, the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

For the last 16 years I’ve been lucky enough to be involved with Room to Read, an eye-wateringly successful initiative to spread literacy throughout the developing world that has so far made the lives of nearly 17 million children in south-east Asia, southern Africa and elsewhere so much better by ensuring that they, and their children, are able to read and write.

It was in Sri Lanka that Nick and I were able to go and visit one of their schools and libraries and to see at first hand just what a gift education is. The contrast between the eager, bright-eyed Sri Lankan schoolchildren in their immaculate uniforms soaking up every minute of every lesson and the blasé, sometimes downright hostile, reluctance of so many European and American students could hardly be more marked. Skiving off school is worn as a badge of honour by many of the latter, whereas John Wood, founder of Room to Read, tells stories of children so excited to have access to books at last that they go so far as to break in to their library at night to devour books by torchlight.

I’ve observed a non-identical but slightly similar contrast in attitudes to the job of sommelier between the developing and developed world. I’ve been lucky enough to see student wine waiters at work in the Maldives, Mauritius and South Africa. Even in the Maldives, where the population is Muslim and forbidden to drink alcohol, the trainee wine waiters I encountered could not have been more enthusiastic about learning how to serve wine, and about the background to wine itself. There was clearly joy in learning and in mastering the art of wine service.

The Constance group of hotels in various luxurious spots overlooking the Indian Ocean have a particularly energetic Corporate Sommelier (sic) in Jérôme Faure, who organises an annual competition for their local chefs and sommeliers judged, and in the case of the chefs coached, by incoming luminaries. Earlier this year I watched the three finalists in their sommelier competition as they were put through their paces of serving wine and talking about it. Even though none of them was brought up within a thousand miles of a vineyard, they were clearly bewitched by wine and the desire to share their enthusiasm. One of them was far too nervous to shine in the competition, but I subsequently watched her on the floor of her hotel’s restaurant and could see that she had a natural affinity for, and pride in, the noble business of ensuring that customers’ experience of wine is the very best it can possibly be.

Two and half thousand miles west of Mauritius, in Cape Town, virtually all of the top sommelier jobs are held by economic migrants from Zimbabwe who came to South Africa with nothing, and certainly no experience of wine, but have shown an unexpected aptitude for wine service and an unquenchable thirst for knowledge of it. A film is being made about the ‘Zim somms’ by the same Australian team as made the excellent Red Obsession about the Chinese love affair with wine a few years ago. Blind Ambition, filmed in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Europe, will be launched next year.

Fascinated by their story, I and some of you played a small part in raising funds to get this Zimbabwean team to the World Wine Tasting Championships organised by the French wine magazine Revue du Vin de France in 2017 and have had the pleasure of seeing their extraordinary work ethic and enthusiasm for wine.

All of this is somewhat at odds with the sommelier stereotypes we have in Europe and the US today. The waning stereotype is the snooty, senior wine waiter who pretends to know far more than he does and does his best to intimidate us while bullying us into choosing what he wants to sell rather than what we want to buy. The more modern stereotype somm is a young blood who treats blind tasting and posting on social media as competitive sports, and is obviously more concerned with celebrity than service. (The original film in the three-part SOMM series may unwittingly have played a part here.) A typical career trajectory might be barman, a few months hauling cases and working the floor, wine director, Master Sommelier, then brand ambassador with a few personal wine brands on the side.

This of course is a cynical stereotype and the product of a hideous generalisation, but there must be a grain of truth in my suggestion that too few modern wine waiters are actually interested in waiting on their customers. Master Sommelier Chris Tanghe, chief instructor at Guild of Sommeliers in the US, told me with a rueful sigh recently that he considers the most important part of his job is to remind sommeliers that their purpose is to serve wine and satisfy diners.

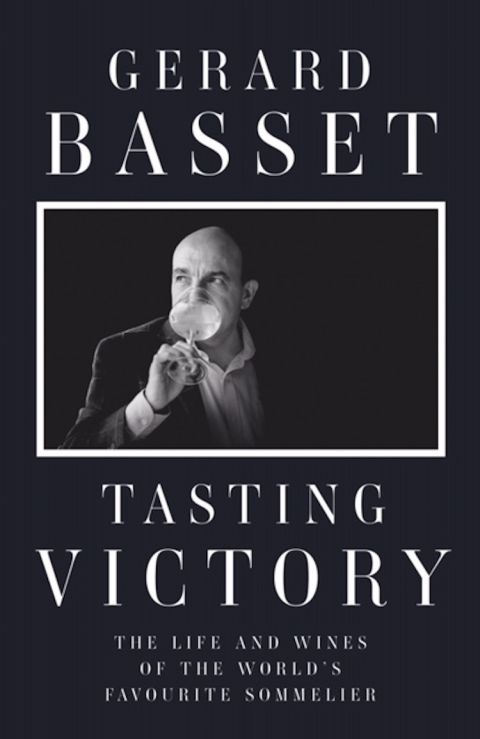

He was over in the UK to make a podcast about the late Gerard Basset, the only person to have won the title Best Sommelier in the World (in 2010) with a British flag draped over his shoulders and probably the most-loved wine waiter ever. We agreed that Gerard’s overarching quality was his modesty, and that he saw his mission as encouraging whole new generations of sommeliers dedicated to the notion of service.

Perhaps it was partly because Gerard was born and brought up in France that he was unaffected by what has been a notion prevalent in more northerly parts of Europe (and particularly in the Soviet bloc when communism was at its height) that there is something demeaning about serving people. It probably explains why such an extraordinarily high proportion of restaurant staff in Britain at least are from mainland Europe. But I think among a younger generation of Brits this is changing – albeit not before time. They are imposing a new style of service in bars and restaurants which manages to be both friendly and efficient, and is lightyears from the old snooty stereotype. I am never prouder of our Oxford-educated son than when customers in his restaurants tell me how much they enjoyed being waited on by him or his staff.

When Gerard’s inspirational memoir Tasting Victory is published by Unbound early next year, I hope it will be widely read by sommeliers and aspiring sommeliers, and that it will encourage them to take as much delight in delivering the right wines to diners all over the world as he did. The jacket, approved by his widow Nina and son Romané, is reproduced below.