Nicholas Daddona was one of the winners of our hospo food and wine pairing competition. Here he strives for more glory, including this brief bio: 'Nick Daddona is a Boston, Massachusetts based sommelier and beverage director of Boston Urban Hospitality, a local multi-concept restaurant group. He is currently studying to pass the diploma portion of the Court of Master Sommeliers exam, along with his wife Lauren. They are lovers of food & wine, travel, and connecting people.' For other entries in our sustainability wine writing competition so far published, see this guide.

‘The most important thing,’ Jasmine says, ‘is our 200 year plan, how can we be sustainable moving forward. Nourish the farm, and nourish the people who help maintain the land.’

I spoke to Jasmine Hirsch, the General Manager and Winemaker of Hirsch Vineyards, or ‘The Farm’ as she and her father David call it. We spoke about sustainability: programs for CO2 being locked in the soil, for giving back to the grid net positive through solar panels, for action on carbon relating to treatments and machine use, for techniques in battling erosion that have certainly saved the land from being swept into the creeks and ravines of the jagged Sonoma Coast.

I asked what sustainability meant to an independent, family-run winery. Her answer surprised me.

David Hirsch purchased just over 445 hectares in the late 1970’s as a remote oasis from busy life in Santa Cruz, about 3 hours away by car, tucked into the second ridge-line from the cold Pacific. The climate is refrigerated sunshine, deceptively cool at times, and some of the highest rainfall in wine-growing California. The soil is a hodgepodge: clay, sandstone and loam dot the ridges due largely to the fault lines below; the name is also taken for their flagship cuvée, ‘San Andreas Fault.’

When the land moved to David’s stewardship in 1978, he had known the land was used to ranch mostly sheep. In the past, it was a dense redwood forest which was clear cut to help rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. What he did not expect was that upon investigation, the land was scarred and wounded. The previous owners had left tractors and other heavy machinery to rust and rot, over-grazing had damaged the soil, erosion was rampant and non-native grasses had been brought as animal feed. David rolled up his sleeves and thought of where this property would be in 200 years.

Unlike many of his peers, grape growing came as a necessity to heal the land – not a dream of creating a great wine. A friend from Santa Cruz mentioned the land would be fantastic for Pinot Noir, he then planted a few vines in hope of helping support his efforts to rehabilitate the farm. This revenue helped clean the land, what was a hectare or so of Pinot Noir and some white grapes planted in 1980 became 27.5 ha, after a modest expansion from 1990 to 1995. Always thinking of the land as a whole entity, he included space for native plants, gardens, and land earmarked for sustainable ranching.

Always with an eye towards the true toll of farming, David would weigh all decisions: treatment for weeds or use of machine, a burned gallon of gas or a treatment’s effect on the soil? These considerations remained at the forefront of his mind throughout the 1980’s. Swift changes on the farm were seldom, though this could be one of the wineries greatest strengths; decisions are heavily personal, requiring much evaluation.

Hirsch has grown grapes for some of the top wineries in California, but it was while working with Ted Lemon of Littorai that biodynamics took hold. The vineyard was farmed with 100% biodynamic practices as of 2014. Careful curiosity and the possibility of innovation color all decisions: solar panels on the winery put energy back into the grid, reforestation efforts control erosion, watershed management nurse the creeks to health, native plants flourish as cover crop between rows of vines. The vineyard isn’t certified, though David is in contact with the Demeter organization and uses many of their techniques, choosing instead to maintain the ability to do what is best for his farm. I can hear him saying ‘the label is not important, doing is important.’ That pioneering spirit does not wane easily!

The Hirsch’s always looked at the farm as a single unit – biodynamics helped. They then looked to expand life in the vineyard, beginning with people. Jasmine spoke of biodynamics and biodiversity coming from the farmer to the land and working in tandem. All of the decisions come from the ability to steward the land. No project is this more in line with their vision than their employee share program. The acres devoted to non-viticulture produces quite a bounty several times a year. This product is shared with employees, those that help nourish the farm, bringing the loop to a smaller degree of being closed.

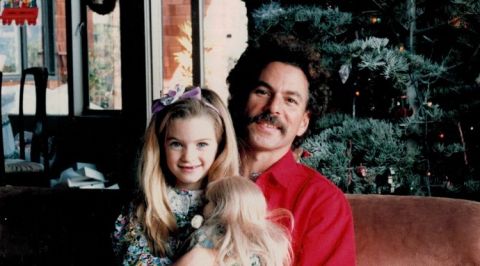

When asked about sustainability and what makes David most proud – the first answer was not about biodiversity, solar panels, or charitable giving. It was his 200-year plan. The 200-year plan is new each day, it’s a mission and a beacon. ‘Each day is another opportunity to look at where the farm will be in 200 years.’ David has worked his hardest to succeed in his most important challenge: intergenerational sustainability. How can he pass on the stewardship of the land to his daughter? How can he pass the curiosity, the heart and soul of the farm?

In May 2014, David, as most days, was working on the farm and disaster struck. After the accident, it was confirmed that he will likely be paralyzed from the chest down permanently. It was months until he was able to make it back to the farm on the extreme Sonoma Coast, Jasmine was by his side. His daughter had been bringing a light to Hirsch Vineyard through wine sales since 2008. In 2015 she took over as General Manager and in 2019 as Head Winemaker.

‘Farms and wineries are the most vulnerable when the property is being passed,’ Jasmine said, ‘the three most vulnerable areas are taxes, family conflict, and disasters, which can happen to us as a society or in our family.’ As she continued, she made it clear that possession of the vineyard is not the right of passage, it is understanding the spirit of the land of which she and her family are now a part. This is intergenerational sustainability.

For all the information available about the winery, the most vibrant piece of the story appears when speaking with Jasmine Hirsch, evidence that the flame still burns brightly. As the mantle of responsibility sits so squarely on her shoulders, I look forward to serving a bottle of Hirsch Vineyards for years to come.

(Both photographs are owned by Hirsch vineyards and have provided permission for use.)