Is it the approach of a new millennium that is making us all so anniversary-conscious? Or is it that I have been a parasite on the wine business for so long that more and more people are asking me to share their significantly celebratory bottles with them? I don't know.

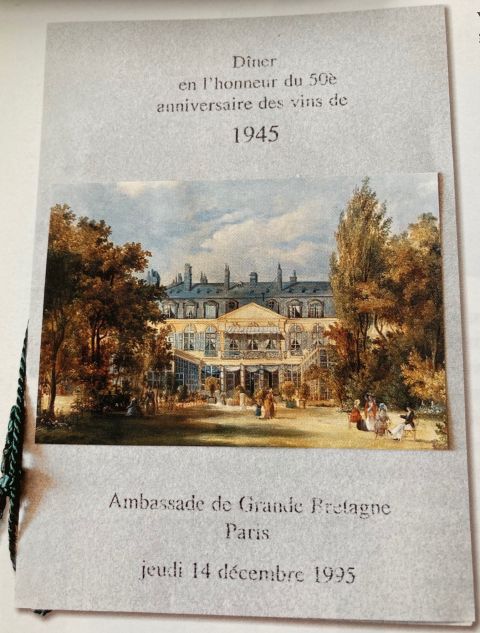

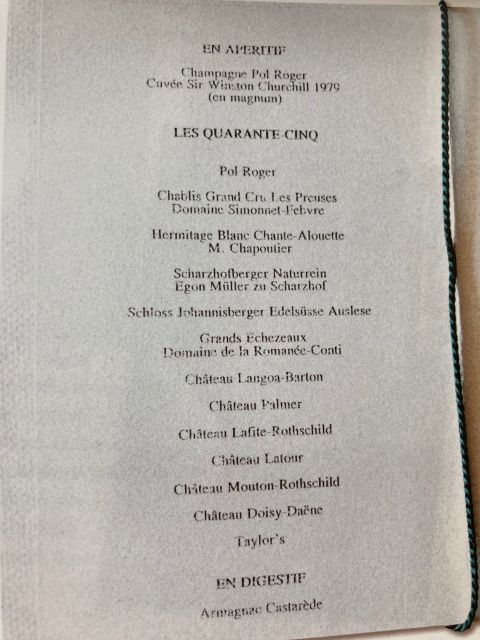

What I do know is that 14 December 1995 was one of the more extraordinary days of my life. Sir Christopher Mallaby and his French wife were as keen on fine wine as you might expect of Her Britannic Majesty's then ambassador to France. At the beginning of that year he'd been reminded by Hugh Johnson and Peter A Sichel that 1995 was the fiftieth anniversary of the great 1945 vintage, a crop that produced such fine wine all over Europe it has come to be regarded as Nature's celebration of the peace that had just broken out. Wouldn't it be a fine idea, they suggested, to organise a dinner at your magnificent embassy in Paris [seen above from the garden in very un-wintry weather; and below on the cover of the menu, taken from Hugh Johnson's 2012 autobiography A Life Uncorked] at which some of the best 1945s are drunk with important representatives of the most significant nations involved in that peace, and us of course, and a few mates?

I was absolutely thrilled to find myself counted a mate, not least because my diplomat cousin Michael Arthur, another great-grandchild of James Forfar Dott the cooper, was based in Paris at that stage and stationed in the embassy's handsome gatehouse where I could so conveniently stay the night.

There were just two problems with this dream date. One was that it coincided with the BBC Governors' Christmas Lunch. This may seem to have little to do with the story but, if you are an independent television producer and depend for much of your income on the nation's most important broadcaster, your instinct is not to refuse invitations from the BBC, especially ones as significant as this.

The 1945 dinner was due to start at eight in the middle of Paris, so in normal circumstances, even with the hour one loses flying to France from London, it would have been a fairly leisurely journey from the lunch to the dinner table. But, and this was the second problem, this was December 1995. Paris was in the grip of the most crippling industrial unrest it had seen for years. Public transport systems had ground to a halt. The newspapers were full of stories of people walking five hours to work or sleeping in offices, and 20-mile tailbacks on the périphérique. It was impossible therefore to know how long it would take me to get from the airport to the embassy, always assuming my four o'clock flight wasn't affected by strike action.

I therefore carefully chose an outfit that would do for both engagements and arrived at BBC Television Centre deliberately early, straight from Will's end-of-term assembly, because I knew I would have to leave so early. To my horror I found at this Governors' annual get-together, routinely leavened with notable characters from BBC programmes of the year, that I'd been put in the place of honour, on the right of the chairman of governors Marmaduke Hussey. I was amused, not least by his uninhibited conversational style, but also embarrassed about leaving a gap on the top table so early. On the other hand, as 'Dukey' agreed, it was not difficult to choose between staying for BBC Christmas pudding and maximising my chances of tasting Pol Roger 1945, the aperitif planned in Paris. So I dashed off from Television Centre with unseemly haste in search of a taxi, still trying to work out which vintage of Roilette Fleurie had been served with the turkey.

The flight was mercifully unscathed by militant air-traffic controllers and touched down at snowy Charles de Gaulle just after six o'clock French time. I sped off towards the city in a taxi feeling pretty optimistic. We did very well for the first half of the journey, but after about 20 minutes the traffic slowed virtually to a standstill. I seemed to sit under a giant Grundig sign for hours. Lorry drivers pulled out of their cabs to swap horror stories. We crawled towards the apartment blocks on the edge of the city. I imagined arriving at the heavy gates of the Embassy at midnight, asking if I could please be allowed in to sip what was left in the bottom of the leftover bottles.

Slowly, agonisingly slowly, the four-lane highway gave way to three-lane boulevards. High-rise apartment blocks gave way to the six-storey tenements that constitute central Paris. It was was 7.30 and I was inching into town, but still two or three miles from my destination I worked out, after peering through the darkness at the street signs and my little street plan. I paid the frightening number of francs on the meter and set off south as directly as I could. [No Google maps then.]

Walking was so preferable to being imprisoned in a car in these circumstances that I felt quite liberated, and triumphant when I found myself at the embassy gates by 8.20 — almost early by French standards. After throwing my overnight bag on to my bed in the gatehouse, I hurried across the courtyard towards the grand entrance that for so many of us will be forever associated with Mrs Thatcher's downfall five years earlier. It was on these steps that we saw her reaction to the news that a crucial vote back in London had gone against her. It was here that we knew, and she didn't, that all that lay ahead for her was speechifying and memoir-writing. As I crossed the gravel I couldn't resist trying a brisk little running dip with my handbag, just the way she used to. What a good mood I was in. I'd made it!

And there they were, still sipping the warm-up champagne, not yet the deeply savoury Pol Roger 1945 but 'just' a magnum of Pol Roger's 1979 vintage of its top blend, Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill, an appropriate enough name in the circumstances. It was possible to work out more or less what we were going to drink by looking at the embassy's guest list: Christian Pol-Roger of course; cousins Eric and Philippine de Rothschild (the latter stuck for two hours in her limo); Peter Sichel of Bordeaux, co-instigator, of course (thereby assuring us of Chåteau Palmer); urbane Anthony Barton, who'd brought his Chåteau Langoa-Barton; Alistair Robertson of Taylor's port (what a lovely thing to look forward to); most significantly for this celebration of peace Egon Müller [father of the current Egon] from the Saar in Germany; and Jean de Castarède from Armagnac country. Hugh Johnson and Michael Broadbent, without whom no serious wine party is complete, were there and, like everyone else, had a story of pilgrimage in difficult circumstances to tell. The one guest who had no excuse to be late, the glamorous Pamela Harriman from the American Embassy next door, duly made an entrance and I had the unnerving experience of apparently being invisible even when introduced to this famous man-eater. The French prime minister, Alain Juppé, and the German ambassador had been invited to add diplomatic gravitas, but were engaged in weightier matters, not least the social unrest in France and the signing of the Bosnian peace accord with Clinton and Chirac, which was also taking place that night in Paris.

I felt quite ridiculously privileged as we moved through to the Borghese salon that is now the embassy's dining-room. What had I done to deserve an invitation to this wonderfully sybaritic event? A grand cru Chablis from Simonnet-Febvre and Chapoutier's Hermitage Blanc, Chante Alouette, were served with the first course salad and it was the 50-year-old Chablis that was the nervy, steely revelation. How dare people use the name of this obviously noble wine on any old medium-dry white rubbish? A fellow crusader against this travesty, and my TV co-star, The New York Times's Frank Prial [who features throughout Elaine's recent four-part story of California Chardonnay], arrived during this first course. He had come only from the other side of Paris but had done the decent thing when faced with a particularly challenging social dilemma. In view of the strikes, the embassy Rolls had been sent for Frank, but it, inevitably, became enmired in the traffic. Frank managed to restrain himself from ungraciously leaping out of it to finish the journey, far more effectively, on foot. I’m not sure I would have done.

With our sautéed foie gras (it had to come) was a Schloss Johannisberg Auslese and the last two bottles of the wine Egon Müller himself made from a blend of everything he could produce in that extraordinary year from his family's Scharzhofberg vineyard in the Saar. He told movingly of how he'd returned from the Russian front to find the weeds higher than the vines, which had been so neglected that yields were minuscule. Perhaps that's why the soaring descant of this dryish, still-youthful 1945 was so thrilling, although the lively richness of the coppery Auslese suited the sweetness of the dish better.

Aubert de Villaine had sent a Grands Echézeaux 1945 from the cellars of the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti to provide the perfect light, game-scented bridge from whites to reds. The array of 1945 bordeaux was prodigious: Langoa and Palmer followed by the three Pauillac first growths, Hugh as a director of Latour having persuaded its new French owner [François Pinault had just taken it over from Pearson] to do the decent thing. Both of the third growths acquitted themselves well in this company. I would have felt terribly nervous if I had been Anthony Barton or Peter Sichel, although I suppose they must have used the occasion as an excuse to open another bottle beforehand. Peter Sichel had brought with him some extracts from the diaries of the famous Bordeaux merchant family Lawton. A typical entry read: 'Very bad frost this morning. Hitler dead.'

If anything, the three Pauillac greats had become even more polarised, the Lafite all dancing and ethereal and reaching the heights that only Lafite at its best can ('just like Eric: bashful, elegant, puckish', I wrote); the Latour a big solid Winston of a wine, powerful and gentlemanly; the Mouton, with eucalyptus and cassis again obvious on the nose, so sweet and alcoholic it twas almost porty. About the Mouton I wrote 'E-N-O-R-M-E...to think it was only a second growth when this was made!' The Doisy-Daëne was a very respectable accompaniment to our almond tart but was trounced by the '45 Taylor's. Alistair Robertson of Taylor's was sitting next to me, and told me how he'd been evacuated from Portugal to the north of England during the war, and how many in the port trade doubted that 1945 would be a great vintage. 'But it just closed up for years and years and then emerged tasting like this.' This was my sort of port, burnished with many a layer of experience and a round, jewel-like whole, rather than a callow mixture of alcohol and sugar.

With great restraint, I declined the brandy and coffee, and was amazed, when I finally floated back over the courtyard to my gatehouse billet (no Thatcher imitations this time), to find Mme Christian Pol-Roger, who'd presumably had to grab a sandwich for supper, sitting patiently in her husband's car, leather driving gloves ready on the wheel, waiting to drive him home. There's another test I would fail.