Some time over the next few months renowned Barolo producer Giuseppe Rinaldi of Piemonte has to make an extremely important decision. He lives in the cavernous brick house and idiosyncratic winery (pictured) that his grandfather built on the edge of the village long before its wine was revered from San Francisco to Sydney and is, perhaps not surprisingly, famous for his sense of history. He has probably read more of the ancient texts about Italy's most famous wine – aphoristically the 'wine of kings and king of wines' – than any other producer of it.

As a result of his researches, since 1990 his two grandest wines, those for which he is most famous, have been made up of a blend of the produce of what he reckons are two complementary vineyards, or crus as they have been known in Barolo. Brunate, rich in sandstone, is blended with Rinaldi's wine from the calcareous marls of Le Coste vineyard, just as his wine from the marls of the Cannubi cru is blended with the produce of the sandstone Ravera vineyard close to his house. Even the youngest vintages of these bi-cru blends sell from £90, or $120, a bottle.

But from next year when the 2010 vintage of Barolo will be launched, a new rule comes into force which prohibits more than one cru name on Barolo labels. Rinaldi, who does not mince his words, is hopping mad. 'The whole tradition of Barolo was blending,' he stressed, in the lee of his massive ancient wooden casks, even invoking the name of the creator of modern Barolo as a dry wine, Giulietta Falletti, who, he claims, not only blended within the Barolo commune but between different communes such as Serralunga d'Alba and La Morra.

'What’s the thinking behind this crazy new rule?' he asked me and his 25-year-old agronomist daughter Carlotta, before snorting, 'all these rules are made in Rome anyway where they know nothing. It must be linked to the big lobbies. Do you know how many bodies we have regulating Italian wine? Nine! There were eight until recently. The French have only three.'

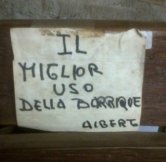

He is no friend of the authorities. His tenebrous cellar, hung with drying salami and tobacco leaves, decorated with slogans such as 'No Barrique, No Berlusconi', was inspected by officials four times last year, inspections that resulted in a fine of €2,500 because his use of the name Ruchè on the labels of his 2,000 bottles of Vino da Tavola made from that local grape was deemed illegal. Another notice in his cellar advertises his distaste for barriques. The chair above is made out of a dismembered barrique with the notice below advertising that this is the best use for one taped to the top of it …

However much Rinaldi seems to relish conflict, the question of how to blend and label his Barolo crus will have to be resolved by early next year. He assures me that he does not blend the wine from different crus until just before bottling (although I noticed that on the giant cask of Brunate 2010 he gave me to taste was written '+3hl Le Coste' in chalk) so the Rinaldi family have some time to consider the options. He shook his head and claimed that the problem will have to be solved by 'the women who have assumed power', a reference to Carlotta and her 28-year-old oenologist sister Marta who also works in the winery but was absent during my visit. Carlotta looked decidedly unconvinced that the decision-making will be turned over to them.

It is difficult to imagine that the Rinaldis will willingly change their wines to fall in with a distant diktat that they should contain the produce of only one cru. One option would be to dream up and register fantasy names for their blends as, for example, Luciano Sandrone, and daughter, have done with their Le Vigne blend. In the Napa Valley Brunate-Le Coste might be renamed Il Vino de Marta while Cannubi-Ravera would become Il Vino de Carlotta. But it's difficult to imagine a traditionalist like Beppe Rinaldi following this path.

The truth is that although the Barolo zone in the Langhe hills is far from extensive, it is quite a challenge to understand. If you don't live there, how are you to tell which is a cru name and which a proprietary brand? And this confusion will presumably persist even after recent attempts at geographical clarification.

Aware of a certain anarchy in nomenclature, the principal generic Barolo body, the Consorzio, recently required each commune to register their crus for an official listing of them, a move related to the new ban on bi-cru naming. The result is an official list of no fewer than 180 crus shared between the fewer than 1,000 hectares of vineyards capable of producing Barolo – despite the recent dramatic increase in plantings of the required Nebbiolo vines. It is perhaps telling that an official Barolo map created before this recent list was compiled put the number of 'great' vineyards, or crus, at just 36. Needless to say, different communes reacted differently to the request, Monforte d'Alba in particular submitting questionably enlarged areas for its most famous crus – much to the fury of those who own the finest plots in the classical heartland.

This new system very much reflects the French appellation contrôlée system in general and that of Burgundy in particular. No one in Barolo loves Burgundy more than Beppe Rinaldi who makes regular pilgrimages there on his motorbike, but his comment on the scheme was, 'it's idiotic. The Langhe is not the Côte d'Or. Anyone can see that at a glance. We're not monkeys. We must have our own dignity.'

The authorities may be understandably wary of decreeing one cru to be superior to another, but the admirably hard-working Italian wine cartographer Alessandro Masnaghetti has trudged the hillsides to come up with not only unrivalled maps of them but his own unofficial ranking, from none to five stars – and all available in digital form, as either an e-book or a series of apps (see Barolo 2001-2008 Assagi e Classificazione). This brave man (who does admittedly live some way away in Emilia-Romagna) has now started to map Bordeaux in similar detail.

I asked Rinaldi what he thought of Masnaghetti's work and was not surprised to hear that he approved. 'But', he added, it's so sad that it was a journalist and not the Consorzio who did it.'

See Walter Speller's unrivalled comprehensive report on the recently released 2009 vintage of Barolo including tasting notes on more than 200 of them.

After this year's exceptionally wet spring, the Barolo vineyards are suffering as never before since 1978 from peronospera (downy mildew). Carlotta kindly went out into the vineyard to find me a leaf to demonstrate the yellow spots that develop on leaves of peronospera-affected vines.

RECOMMENDED BAROLOS

Some seriously fine Barolo I tasted recently in Piemonte. See Wallowing in Barolo for full tasting notes.

Azelia, San Rocco 2006

Luigi Baudana 2007

Pio Cesare, Ornato 2009

Michele Chiarlo, Cerequio 2001, 2004 and 2009

Damilano, Cerequio 2009

Aldo Conterno, Bussia 2009

Franco M Martinetti, Marasco* 2007

Cordero di Montezemolo, Bricco Gattera 2008

E Pira de Chiara Boschis, Cannubi 2005

Giuseppe Rinaldi, Brunate-Le Coste and Cannubi San Lorenzo-Ravera 2008

Rivetto, Briccolina 2007

Luciano Sandrone, Cannubi Boschis 2003

Paulo Scavino, Bric del Fiasc* 1989

* not one of the official crus