For other Bordeaux coverage this week, see UGC 2017s in bottle, part 1 – Médoc and sweet whites and UGC 2017s in bottle, part 2 – Graves and right bank. See also Joined-up science at Bordeaux's ISVV – part 1 for an insight into the connections between academia and winegrowing.

Now that the grapes are all in, and the wine safely in the tanks and barrels, there's a chance to reflect on the year in the vineyard and how the new Bordeaux vintage has shaped up. So here is my Bordeaux 2019 update. It’s been my thing for a few years now to put some of the weather statistics into some context by drumming up a few graphs and charts, alongside some photos and explanatory words.

This was my twentieth full season in Bordeaux, having arrived just before the harvest in 1999, with 2000 being my first full vintage viewed at close hand. My experience is that no two vintages have been the same and, despite the considerable changes across two decades and the enormous investments in new wineries, equipment, viticulture, people and so on, it is still the weather – and how we and the vines respond to it – that determines the quality and quantity.

Bordeaux 2019 – a very good year

'You're joking – not another one?' No, really, Bordeaux 2019 is a very good to excellent vintage. It wasn't straightforward, with heatwaves, drought and a rainy finish along the way, but Bordeaux enjoyed a long, dry summer and harvest with just enough rain, and no disasters like the late spring frost of 2017 or the significant losses to mildew that some growers experienced in 2018.

At the top end, it’s becoming an embarrassment of riches. 2019 makes it six very good years in a row for the northern Haut-Médoc appellations of St-Julien (pictured above), Pauillac and St-Estèphe, which were largely untouched by the 2017 frost and produced many fine 2014s, and likewise for the top estates on the plateau of Pomerol.

The much larger right-bank appellation of St-Émilion (above), which saw considerable frost damage in 2017, has seen four winners out of the last five with 2015, 2016, 2018 and 2019, and you can include Margaux and Pessac-Léognan from the left bank in the same context. (Many estates did well in 2017 but it was inconsistent. See this guide to all our coverage of that vintage, as well as today's article on a selection of 2017s in bottle.)

Hundreds of petits châteaux across the region, from the Graves to the Médoc, from Fronsac to the Côtes and generic Bordeaux Supérieurs, should also be able to line up impressive verticals of those same four vintages (plus 2017 too in many cases) at considerably lower prices. For trade purchasers of bulk wine, it’s a buyers’ market.

The dry whites show great promise in 2019 and, although I haven’t been down to Sauternes since the first week of October, the noble rot should have taken hold mid month. There's a strong chance that the unbroken run of successful sweet white vintages in all the 'odd' years this century is set to continue.

Bordeaux 2019 – 10 observations on the growing season

- A dry year with 25% less rain overall than the average up to the end of the harvest.

- A mild winter saw average rainfall in November, December and January, then a dry February and March.

- Spring rainfall (Q2) was close to the norm from April budbreak through to June flowering.

- Some localised spring frosts and limited hail damage later on, though relatively small losses.

- Flowering in early June began well but a rainy, chilly spell led to uneven fruit set in many vineyards.

- No major disasters like the frost of April 2017 or the mildew that had a significant impact on multiple growers in 2018.

- A long, hot summer saw over three months of mostly fine weather from mid June to the fourth Sunday of September.

- Heatwaves in late June and 40 ˚C (104 °F) in late July put some vines under pressure – though this was pre-ripening.

- Heavy rain on the last Friday in July, just after a heatwave, refreshed many vineyards just in time.

- Light rain in among the hot weather in August and mid September helped the vines.

Bordeaux 2019 – 10 observations about the harvest

- A long harvest from late August for early dry whites and crémants, to mid October for late reds and sweet whites.

- The harvest began with dry whites in late August through to the middle of September in fine conditions.

- On paper, despite the summer heatwaves and hot mid September, it was a moderately late (or normal) red harvest.

- The Merlot harvest in earlier-ripening areas such as Pomerol began tentatively in the second week of September.

- Most of the red harvest took place in the second half of September and first half of October.

- The lack of rain through the summer had an impact on the size of the berries, on the amount of juice and the yield in many vineyards.

- The weather turned on 22 September after a hot fortnight with rain for a few days, before clearing until 14 October.

- There was minimal pressure of rot so châteaux were not forced to pick early, though vigilance was needed.

- Alcohol levels are in line with a dry, warm year, with Merlots around 14–14.5+% and Cabernets 13–14%.

- Yields range from moderate to plentiful, depending on the June flowering and the effectsof drought and a dry year.

- Overall volumes will probably be a little short of the 10-year average – not far off 2018, up on 2017, down on 2016.

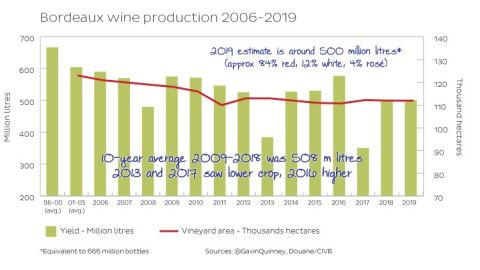

Comparing Bordeaux production

Overall 2019 volume will probably be a little less than the 10-year average of 508 million litres (2009–2018). Note that 2013 and 2017 were the low crops of the last decade and they brought down the average figure: the pre-2013 10-year average, for 2003–2012, was 566 million litres, albeit with a slightly larger vineyard area (an average in those years of 118,000 ha/291,600 acres versus 113,000 in the last decade).

2019 yields range from moderate to plentiful, depending on flowering and the impact of the drought. Most estates at the top end will be producing 35hl/ha to 55hl/ha in 2019, with greater consistency in 2019 from one château to another than in 2018, when mildew significantly affected some more than others. Maximum yields are set at 50–57hl/ha depending on the appellation, with a higher quota for dry white, with up to 65hl/ha for Bordeaux blanc (such as the Sauvignon Blanc at Ch Bauduc, below).

These production figures refer to all wine from Bordeaux appellations – about 57% being a generic Bordeaux and 43% from designated areas or appellations within the Bordeaux AOP. About 97% of all wine in the Gironde will be declared by growers this December as Bordeaux AOP, with the small amount that’s left being Vin de France or IGP.

The OIV estimated on 31 October that 2019 overall French wine production at 41.9 million hectolitres (4,190 million litres) will be 15% down on 2018 and 7% down on the 5-year average.

Monthly rainfall

In general, the 2018–2019 autumn and winter rainfall was about average in November, December and January, but it was pretty dry in February and March. The region had, quite significantly, a rainfall deficit between October 2018 and March 2019, with about 100 mm (4 in) less rain on average than the norm (530 mm/21.7 in). There was though a 250 mm difference between one area and another, with some zones receiving markedly unequal amounts of rain. 2018–2019 saw a much drier October–March period than in 2017–2018 but it was not as dry as the same six-month stretch in 2016–2017.

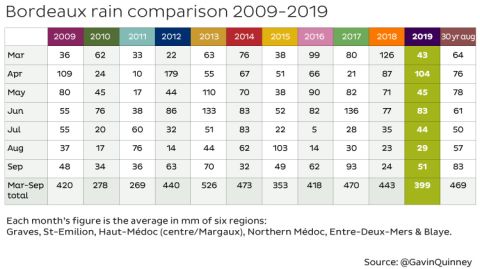

Here's a table showing monthly rainfall from March to September in the Bordeaux region over the last decade compared with the commonly quoted Bordeaux 30-year average. I've taken the readings from six weather stations from around Bordeaux for a more general impression. The level of rain is significant because, among other things, under appellation rules growers are not allowed to irrigate their vines (except infant ones that are not yet in production).

The best Bordeaux vintages, such as 2009, 2010 and 2016, have just enough rain – but not too much – in July, August and September, after a normal, wetter spring. Bordeaux 2019 saw enough spring rain and then a dry summer and September. Timing is important: as we shall see, most of the rain in June fell in the first half of the month, while in July most fell on one day at the end, and in September, too, most of the rain came near the end of the month.

Overall it was a dry growing season. What isn't shown here is the variation between subregions, and the detail. Margaux, for example, had 466 mm (18.3 in) of rain from 1 January to 13 October (the end of the harvest there), a third down on the 30-year average of over 700 mm. St-Émilion saw 535 mm and Léognan 571 mm in that same period.

Monthly temperatures

Rainfall tells one part of the story but obviously the vines need sunshine. And, for the fruit, cool nights to contrast with hot days.

Here are the average temperatures by month for those same six subregions, with the 30-year average for Bordeaux in brackets. As a backdrop, the autumn and winter 2018–2019 was fairly mild, with the exception of a cold January. Following the April budbreak and the early-season growth, May 2019 was noticeably cooler than average, before the flowering began at the end of the month. June, August and September were broadly in line with the average, and July considerably warmer.

March 10.9°C (10.2°C)

April 12.1°C (12.4°C)

May 14.5°C (16.1°C)

June 19.2˚C (19.3°C)

July 23°C (21.3°C)

August 21.2°C (21.4°C)

September 18.9° (18.5°C)

Comparing temperatures and timing

Here's a more complex table showing a snapshot of heat accumulation indicating the progress of the vines during the growing season in each vintage. By adding up the daily average temperatures since 1 January, but removing any average temperatures below 10 ˚C (50 ºF), the grid shows how the recent vintages compare at different stages of the growing season. The temperatures are taken from a local weather station, 10 miles/16 km east of Bordeaux. The 'Total °C’ and the dates mentioned is the accumulation of the average daily temperatures, subtracting 10˚C each day, by that date.

23 May was just before flowering in 2019, and the start of flowering for earlier-ripening years. You can see that 2019 got off to a slow start – as did both the superlative 2016 vintage and the difficult 2013 season, so things can go either way.

27 June was after flowering, with the newly formed grapes mostly at a stage usefully known as petit pois before becoming gros pois. We were some way behind at this stage in 2019, despite a heat surge towards the end of June.

27 July in 2019 was just before veraison, when the grapes change colour. The grapes are at a stage called fermeture de la grappe (bunch closure), when the bunches become fully formed with green, unripe grapes. July 2019 was a hot month – compare the accumulated temperature with, say, 2012 and 2014.

22 August is normally at the end of veraison, with the grapes now starting to ripen fully in the build up to the harvest. Véraison was quite protracted in 2019, fuelling fears of uneven ripeness later on.

The final rows in the table show the date when the degree days reached 800 ˚C and 1500 ˚C respectively. It is not used as a guide but 800 ˚C is a useful marker for when the bunches have been fully formed and before veraison happens. 1500 ˚C often coincides with the end of the white harvest and soon after the start of the reds – all being well.

The figures do give a fair impression. 2011 was an early-ripening year, and 2013 very late when the vines struggled. 2017, despite the widespread spring frost causing so much damage in many parts of Bordeaux, was an early-ripening year. Stylistically, based on this, it would be no surprise if 2019 ended up as a mythical blend of 2012, 2014 and 2016, with a little 2015 thrown in. (By that I mean the charm and drinkability of the 2012s, the straightness and classicism of the 2014s, the freshness and fruity appeal of the 2016s, and the warmth of 2015.)

The growing season

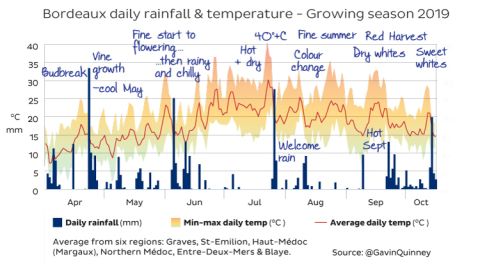

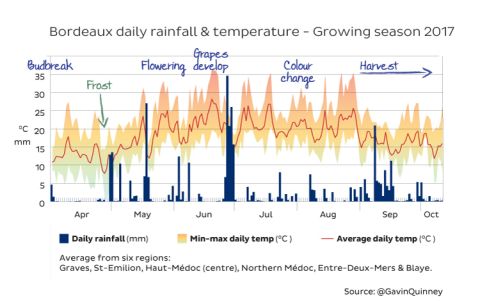

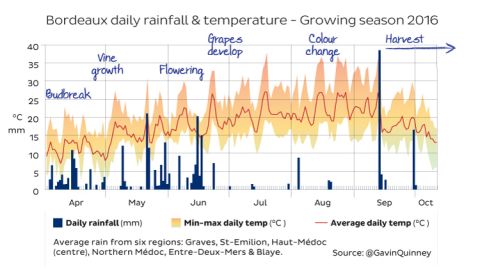

For this graph, I've taken the daily statistics for temperature and rainfall from those six weather stations around Bordeaux to give a more general overview than the localised charts produced by growers and syndicates. I have then averaged out the numbers per day.

Budbreak was in early April and that month was considerably wetter and slightly chillier than the norm in most regions, though with about average rainfall in St-Émilion. There was also a frost alert in mid April, with some localised damage, but nothing on the scale of the damage caused in late April 2017.

As I said above, the growing season got off to a slow start with a cool May, and it then warmed up considerably for the start of the all-important flowering just as we approached the first, glorious weekend of June. Some vineyards flowered successfully over these few days. I was walking around ours, encouraging the vines to hurry up as we could see the forecast, and on the Wednesday it thoroughly poured with rain. There was intermittent rain over the next week or so, and it cooled down considerably. (When this happens during the flowering the tiny flower of fused petals, called the calyptra, doesn’t fall away properly from the male and female elements, and the potential berry isn’t pollinated.)

The result was that many bunches had uneven fruit set, with coulure and millerandage – unformed and variable/undersized berries respectively. The impact varied enormously from one zone or area to another: some vineyards were completely unaffected, while others had uneven bunches from one row or even one plant to the next.

Once the flowering was out of the way, the bunches and grapes grew in fine weather, becoming hot and sunny from the end of the month and throughout a very warm July. Temperatures reached a stifling 40 ˚C (104 °F) on 23 July and many of the vines shut down. Thankfully, heavy rain fell a few days later on the Friday – with most of the July rainfall falling over one or two days.

As far as we can tell, the July heatwave didn't affect the bunches negatively as the grapes had only just formed and were yet to change colour.

We then had more hot weather in the second half of August and then well into September. The chillier early mornings in early September proved to be ideal for harvesting the white grapes.

The harvest

The first grapes to be picked in Bordeaux are the whites for making Crémant and the earlier-ripening vineyards of Pessac-Léognan for their dry whites. Some began at the end of August with others the first week of September. Conditions were ideal for the Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon (below), with fresher mornings and clear weather.

The dry whites of the Graves began in early September and soon after across the Garonne in the Entre-Deux Mers (above) and other parts of Bordeaux. Yields and quality for the dry whites are very promising.

The Merlot harvest in the more precocious areas, such as Pomerol, began in the second week of September and continued from there. Most of the red harvest took place in the second half of September and first half of October.

The harvest changed on the fourth Sunday of the month – the 22nd. Up until then we'd had glorious September weather with temperatures in the high 20s and over 30 ˚C (86 °F). With the autumn equinox approaching on the 23rd, we had rain on the Sunday and then for the next few days, then clear from 26 September until 12 October. The amount varied considerably from region to region: around 50 mm (2 in) in the Entre-Deux-Mers and in the northern Médoc but only half that in Margaux, with 35 mm in St-Émilion and Léognan.

The rain acted as a refresher for the Cabernet Sauvignon that was picked in early October. Many estates in the Médoc concluded their harvest in the second week of October under clear skies. In both St-Émilion and the Médoc that week there seemed to be no pressure from rot, with the grapes coming in in good health.

The lack of rain through the summer had an impact on the size of the berries, the amount of juice and the yield in many vineyards but by no means all. Alcohol levels are what you'd expect from a dry, warm year, with Merlots around 14–14.5+% and Cabernets 13–14%. What will be key is the balancing acidity and the maturity of the tannins.

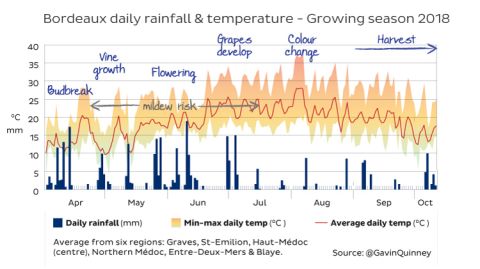

Appendix – comparing 2019 weather with that of 2018, 2017 and 2016

Each year is different. It’s not quite like a box of chocolates but ‘you never know what you’re gonna get'.