Bordeaux 2021 weather and crop report

Gavin Quinney of Château Bauduc provides his usual statistical analysis of the vintage, being picked in welcome fine weather above, that has just been presented en primeur – in person!

Bordeaux welcomed professionals from the world of fine wine – for the first time in three years – for the spring tastings of the latest vintage at the end of April. As the ‘en primeur’ tastings of young samples by critics, commentators and merchants confirmed, 2021 is a comparatively weaker and uneven vintage for reds, even if very good for the whites (which are made in much smaller volumes).

Here’s my report of how the weather during the Bordeaux growing season left a fairly indelible mark on the style of the wines and the volumes produced.

When I say ‘comparatively weaker’ that’s because Bordeaux has seen a string of successful years for reds – namely 2015 (though variable), 2016, 2018, 2019 and 2020 – since the fairly poor harvest of 2013. (2014 was pretty good in parts, and 2017 wasn’t all bad by any means.) 2021 is, as just about everyone would agree, an uneven year, though there are plenty of well-made, attractive reds and not just from the very top estates.

The handsome French word hétérogénéité springs to mind – no fewer than five acute accents and one that sums up Bordeaux 2021 – for the growing season, the crop and the resulting wines. Heterogeneity – ‘the quality or state of being diverse in character or content’.

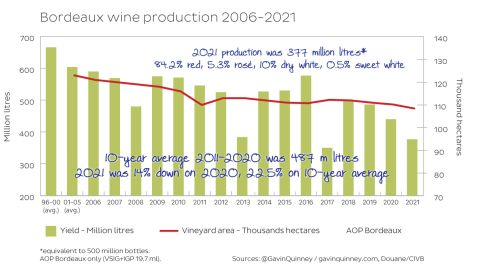

Bordeaux 2021 production compared with recent years

It may be worth taking a look at the size of the overall crop in 2021 as a starting point.

Like 2013 and 2017, 2021 was a low production year. 84.2% was red, 5.3% rosé, 10% dry white and just 0.5% sweet white.

At 377 million litres – the equivalent of 500 million bottles – 2021 saw a drop of 14% on 2020, which itself was a smaller production year at 440 million litres. 2021 was down 22.5% on the 10-year (2011–2020) average of 487 million litres (equivalent to 650 million bottles).

That decade included three smaller crops in 2013, 2017 and, to a lesser extent, 2020. In the noughties, the average annual production from 2001 to 2010 was over 580 million litres, equivalent to over 770 million bottles – well over 50% more annually on average than for 2021.

Here are the 5-year production averages for Bordeaux, by the way:

1986–1990: 536 million litres

1991–1995: 537 million litres

1996–2000: 666 million litres

2001–2005: 604 million litres

2006–2010: 557 million litres

2011–2015: 502 million litres

2016–2020: 470 million litres

More details on the production for 2021 follow below.

The growing season for Bordeaux 2021

This is a chart I’ve put together each year since the 2016 vintage, taking the data from six sub-regions of Bordeaux to get a more representative picture of the vintage. You can see how the different vintages compare at the foot of this article in the appendix.

I’ve included March and October for 2021, unusually, bookended onto the key six months of the growing season from April to September. That’s because the dry and warm spell at the end of March and early April spurred on the bud-break just before the April frost, and at the other end the red harvest took place mostly in the first fortnight of October.

Below, another neighbour’s Merlot, which did not escape the frost of 7 April.

The whole parcel was lost for the year. The frost of early April 2021 follows on from the severe frost across Bordeaux in late April 2017, with damage throughout much of the region. Barsac, Sauternes, the Graves and parts of the right bank were particularly badly hit in 2021.

Note the scribbled text in the graphic above for some of the most significant events through the season. There isn’t room for some important bits, like the fact that we need the vines to feel some water stress after flowering and fruit set – in late June/July – so that they concentrate on producing quality fruit. Heavy rains in the second half of June didn’t help, as well as creating dangerous conditions for the spread of mildew. Below is the impact of mildew on (a neighbour’s) bunches in the summer.

Comparing 2021 rain and temperatures with the average

This graphic below, showing the weekly figures, also provides a useful comparison with the average monthly stats. After a wet December, January and February saw 108 mm/4.3 in and 99 mm/3.9 in of rain respectively and Bordeaux then had a dry March and April. After the early frost had slowed things down, May was colder than normal, and wetter. June was warmer thanks to some fine weather during the flowering period before the heavy rains. July and August were comparatively cool before a late summer surge in the first half of September.

The dry whites were harvested in good conditions in September after a dry August which, conveniently for white grapes, wasn’t too hot.

Rainfall each month, 2009–2021

2021 saw a dry March and April, followed by a wet May and deluges in June. In general, there’s nothing wrong at all with a wet spring as long as it’s followed by a dry summer. (And so long as you keep any vine maladies like mildew at bay.) See 2009, 2016, 2018 and 2019 for example – all very good years. A wet June can be problematic for reds however – as in 2013, 2017 and 2021. Thankfully the flowering went quite well in June 2021 due to some timely sunshine.

Monthly temperatures, 2009–2021

As you can see, 2021 was cooler overall, notably in July and August but also in May. Thankfully September was warmer and crucial for the final ripening of the grapes.

Production and yields

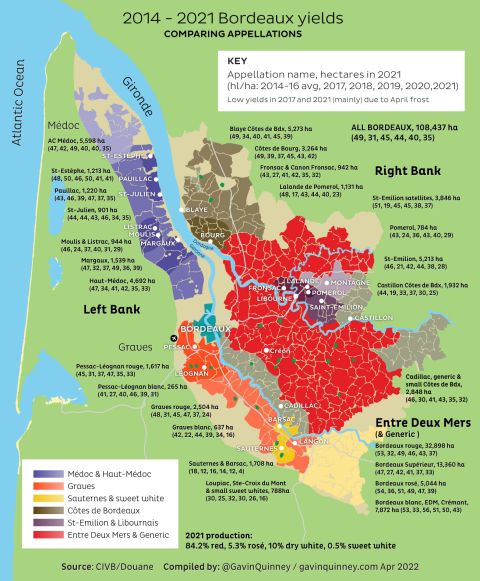

As a lot of appellation names follow, it’s useful to have a map. (We’re based near Créon by the way, south-east of the city of Bordeaux.)

Production split by appellation in 2021

In volume terms, well over half of the production comes from the generic Bordeaux red appellations and the Côtes de Bordeaux.

Low yields for most appellations in 2021

Yields per hectare were quite low across the board in 2021, although results varied considerably from one vineyard to another. 33 hl/ha (roughly 1.9 ton/acre) for Bordeaux Supérieur, for example, is a barely tenable proposition, financially. Yields for Bordeaux blancs were less disastrous, while the sweet-white appellations had their worst yields for a long time, chiefly due to the April frosts.

Comparing the yields for top appellations

For the most prestigious and sought-after appellations, there were mixed fortunes. Overall, compare the lower yields of recent years to earlier vintages (and 2004 and 2005 were generous years too). St-Estèphe usually outperforms its neighbours in terms of yields, while St-Émilion and Pomerol saw yields of below 30 hl/ha (c 1.7 ton/acre), though they can consider themselves fortunate compared with Sauternes and Barsac.

The Bordeaux geek’s map of yields

For this map, I’ve added Pessac-Léognan white and red separately to show how little there is of the excellent whites in 2021. Likewise the Graves.

Appendix – the growing seasons from 2021 back to 2016

Every year is different, of course. Bear in mind that irrigation is not permitted so the rainfall, or lack of it, plays a huge role. Unfortunately the frost in April 2017 and again in April 2021 made a big difference. The other years below produced numerous very good to outstanding wines.

All images kindly provided by Gavin Quinney.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,396 featured articles

- 274,621 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,396 featured articles

- 274,621 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes