Recent Gatwick–Bordeaux flights will have been carrying an additional burden. It is fair to assume that every one of the many wine merchants en route to taste the 2015 vintage last week had in their luggage the 100-page, half-kilo report on the bordeaux market from Liv-ex, the global b-to-b fine-wine marketplace.

This year’s report, published just before the primeurs, showing that is crucial to the success of a Bordeaux vintage, paints a picture of a market on a knife-edge. The 2015 vintage (see this guide to our coverage so far), much more promising in terms of both quality and quantity than any of the four that preceded it, should represent a turning point for the fortunes of France’s dominant fine-wine region.

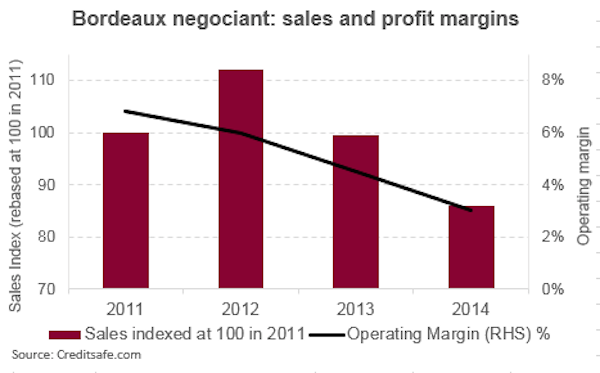

But Liv-ex’s charts show that profitability has plummeted both for Bordeaux négociants and for those who buy from them. Bordeaux négociants’ stocks grew from 246 to 305 days between 2013 and 2014 while their operating margins fell from 7% in 2011 to 3% in 2014. The UK fine-wine trade, which, with their French counterparts, constitute by far the most important buyers of bordeaux en primeur, has seen operating margins fall almost exactly in parallel, even though they keep much less stock.

One of the most telling graphics charts the ex-château prices as a proportion of the final market price once the wines are delivered (more than two years after they are tasted en primeur). For the ill-starred 2011 vintage the château proprietors’ share of profits, admittedly on rather few sales, was well over 90% whereas in 2008, 2005 and 2003 it was only about 40%. The proprietors’ share then dropped down to below 70% for the 2012 vintage that has so far this decade been the most successful vintage for en primeur investors. Liv-ex’s calculations show that on average en primeur buyers have actually lost money on every single vintage since 2008 except for the 2012 vintage, for which a comparison of current mid price and the average merchant’s release price shows a modest gain of 9%.

It is hardly surprising then that trade in en primeur bordeaux has fallen to such low levels. Liv-ex calculate the proportion of en primeur sales on their trading platform as a percentage of total sales of each vintage. Whereas it was 15 and 11% respectively for the 2009 and 2010 vintages, it had fallen to just 1% for both the 2013 and 2014 vintages. Will the superior quality of the 2015 vintage be enough to revitalise the en primeur market?

As Liv-ex note, the health of the market when the 2009 and 2010 vintages were offered was dramatically boosted by a temporary boom in demand from China which seems unlikely to be revived in the current economic climate there. And demand from duty-free Hong Kong from UK merchants, its traditional source of fine wine, has remained flat for most of this decade.

The problem for the UK trade and their customers this time round, unlike when the 2014 vintage was offered a year ago, is the weakening of the pound against the euro, down by 13% since last November. UK merchants have expressed a fear that a sterling bounce after the EU referendum on 23 June may make bordeaux bought then look cheaper than early primeur purchases made before the referendum. David Cameron clearly wasn’t thinking about how inconvenient his chosen date was for bordeaux buyers, sitting as it does at what is usually the tail end of a primeur campaign.

It is not all that long ago that the Americans were seen as the saviours of the Bordeaux market. Certainly the dollar–euro exchange rate has not changed much over the last year, but US merchants seem almost to have dropped the habit of making substantial purchases en primeur – although in Bordeaux last week it seemed as though the Americans were at least visiting and tasting.

Clearly the pricing of the 2015 vintage will be critical. But then commentators like me and the UK merchants say this every year. What has changed is the increased competition from other wine regions for the wine investment budgets of the world’s collectors.

Comparison of the various regions’ share of Liv-ex trades is as good a measure as one can find of global interest in different wines. Until recently bordeaux has been the lifeblood of fine-wine trading the world over. But whereas in 2010 bordeaux represented more than 95% of trades, by last year this had fallen to under 75%.

Despite the small quantities available, burgundy has been in the ascendant – not least with Asia’s wealthier wine lovers. Italian wine became even more important than burgundy last year, however, while champagne trades doubled in volume. But it was the category known by Liv-ex as ‘Rest of the World’ that grew fastest last year: from 2.3 to 5% of trades. Apparently American (for which read California) wine has been the main driver of this – and this on a marketplace which may claim to be global but is very much London-based.

Incidentally the larger Bordeaux négociants argue that Liv-ex is very much less international and conducts many fewer trades than they do. But then they would never dream of offering impartial information on the performance of individual châteaux. That said, several Bordeaux négociants informally confirmed the names on the list of over-performers below.

At a time when confidence is waning in so many other asset classes and commodities, those who have sought to invest in the most sought-after wines may take comfort in Liv-ex’s comparison of the performance of their Fine Wine 100 index with that of the FTSE, gold, copper and Brent crude oil during 2015. Wine trumps them all – in euros.

But another report published last year suggests caution is in order when considering one of the specific wine-investment funds that sprouted from around 2007 at the start of the China-led boom (see Are wine funds the right way to invest in wine?). Dr Philippe Masset and Dr Jean-Philippe Weisskopf of the École Hôtelière de Lausanne examined the performance of six of the most important wine funds and found that two of them managed to underperform the general wine market and that there was huge doubt over the valuations of the only fund that claimed to have substantially overperformed it. Nor were they impressed by the ability of most of the relevant fund managers, who should presumably benefit from the most privileged information available, to read and react to market trends, although they cite the Wine Investment Fund as an exception to this rule.

The bulk of the Liv-ex Bordeaux report is made up of a detailed, vintage-by-vintage analysis of what they deem to be the 70 most significant bordeaux wines, concluding with their average return over 10 years on en primeur purchases. Twenty two of these percentages are negative, but there are still some mid-range wines that have gained in price (see below).

It was the second wines of the first growths that performed best overall in Liv-ex’s analysis of returns on primeur investment – most notably Le Petit Mouton of Ch Mouton Rothschild. The delicious 2008, for example, is now £166 a bottle from Berry Bros & Rudd but was originally offered at €32 by the château. I took this picture on Thursday of en primeur samples being assessed by, inter alia, Steven Spurrier and Neal Martin (in the Grimes t-shirt behind) at Ch Belgrave where négociants Dourthe/CVBG, like many of their peers such as Joanne, Ulysse Cazabonne and Vintex, run a hospitable and useful tasting room. We hope to start publishing my hundreds of tasting notes on Bordeaux 2015 from a week on Monday.

There are tasting notes on multiple vintages of these wines in our 125,000-strong tasting notes database. Stockists from wine-searcher.com.

DEPENDABLE FINE BORDEAUX

Over the last 10 years the following wines have averaged under €100 a bottle and, according to Liv-ex calculations, have significantly gained in value. They are listed in decreasing price order.

Beauséjour Duffau, St-Émilion

Lynch-Bages, Pauillac

Clos Fourtet, St-Émilion

Smith Haut Lafitte, Pessac-Léognan

Beychevelle, St-Julien

Calon-Ségur, St-Estèphe

Duhart-Milon, Pauillac

Clerc Milon, Pauillac

Brane-Cantenac, Margaux

Talbot, St-Julien