Eating out in Macau

This article was also published in the Financial Times.

During the course of what was to prove an increasingly fascinating dinner at A Lorcha, the Macanese restaurant in Macau, formerly a Portuguese colony now a Chinese Special Administrative Area turned gambling joint to rival Las Vegas, my eye was caught by a man sitting at the far corner table.

Wearing jeans, an open neck shirt and seemingly absent mindedly twirling a bunch of keys in his right hand, he seemed obviously to me to be the owner. Although immobile and drinking only water, he surveyed the entire room continuously. He was obviously loitering with intent.

After we had finished our desserts – an excellent rendition of serradura, a concoction of whipped cream and condensed milk topped with crushed biscuit and ice cream covered with hot chocolate – Adriano Neves, who opened A Lorcha 20 years ago with two friends, came to join us.

For someone whose initial career was in the drainage department at the Town Hall he has done extremely well. During this period the restaurant has doubled in size and in the evenings has proved so popular that he invariably has three sittings a night at 6, 8 and 10pm.As a result he has spent the last few years turning down offers from the major hotels to transfer his restaurant into one of their domains. His attitude was straightforward, he explained, “I want to be here to recognize my regular customers.”

Our conversation had begun because I was curious to discover the origins of the restaurant’s name, having been told that A Lorcha is the name of a Portuguese boat with three rows of Chinese sails. Neves smiled at my question before answering. “When we decided to open our restaurant it was simply because we enjoyed cooking for one another. The food here was to be an extension of what we liked eating and the only criterion for its location was that we didn’t want it to be downtown. We found this place which is just round the corner from the famous A-Ma temple and in those days was very quiet and faced right on to the sea. We were sitting outside when suddenly one of these boats went by on its way to the shipyard round the headland and that was the inspiration for the name.”

If Neves, now A Lorcha’s sole owner, were to repeat this exercise today he would have no alternative but to call the restaurant The Busy Highway or The Car Park as it is these rather than the sea which are now visible from the restaurant’s front door. Over the intervening period Macau has doubled in size by building on reclaimed land with its former oyster beds, for example, now the location for some very tall, and expensive, apartments.

Macau may today be a less romantic redoubt than it was but I don’t believe I have ever been anywhere where there seems to be such an insatiable appetite for food that can be satisfied at so many small, relaxed and inexpensive cafes, each managed by such a contrasting cultural mix.

The most obvious source of culinary inspiration remains Portugal, evident in names not just like A Lorcha but also Espace Lisboa on Coloane, or Boa Mesa, Oumun Café and Platao close to the ruins of St Paul’s in the city centre. And while this Portuguese influence has left a distinctive culinary style accumulated from the outposts of its former empire, such as herbs and spices from Goa, Malacca, Angola and Mozambique as well as the odd culinary technique from sojourns in Japan, it has also yielded a disparate race of restaurateurs and chefs.

Neves is Macanese, the son of a former Portuguese soldier sent to Macau and a Chinese mother, and his menu reflects this mix. Alongside the more traditional Portuguese dishes are those from much hotter climes: a large prawn, sliced lengthways, coated with chili and garlic, and then grilled; African chicken, in which the pieces of chicken are cooked and then coated in a spicy sauce of more garlic, coriander, paprika and dried piri-piri; and a crab curry.

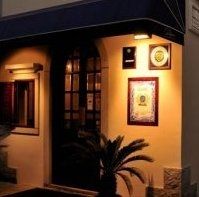

Antonio Coelho, the chef/proprietor of Antonio restaurant in the old town of Taipa (pictured here), once famous for its firework factories, could not be more Portuguese. And nor could the décor of his restaurant with its cool white and blue tiles, dark wooden tables and chairs, and bottles of port along the shelves of its narrow bar.

As he watched a waiter expertly blowtorch a crème brulée at the next table, he explained the two reasons he had left Portugal. “I got divorced and Macau seemed a long way away. But my food is still Portuguese. The beef and chickens come from Brazil, the fish and vegetables from China but everything else is Portuguese. The salami, the cheese, my olive oil and, of course, the sardines. If you don’t buy Portuguese sardines, it can’t be a Portuguese restaurant,” he said, reaching for a cigarette that revealed that, with smoking still allowed in most restaurants (but not A Lorcha since Neves quit two years ago), the importance of the enormous number of Chinese customers close by.

Two other very different factors underpin Macau’s charms as a place to eat and drink.

The first is that as a free port, Macau can still offer low prices. Substantial first courses range from HK$30-40 (£2.50-£3) in the restaurants outside the hotels and main courses are HK$80 (£5.50) to HK$200(£15) for the large, grilled prawns. Portuguese wines, too, are extremely good value and, incongruously, less expensive today than they were under the Portuguese administration.

This price advantage has brought a huge amount of business from Hong Kong. “Until six months ago we used to get a lot of parties in the evening from Hong Kong bankers who would come here for dinner straight from work and go back on the last boat. Apparently this was less expensive for them even with the cost of the journey than to eat in Hong Kong. But sometimes this dependency can break down. Because of the fog today and the fact that the boat trip took three hours rather than one from Hong Kong I lost a third of my bookings,” Neves explained, one particularly grey day in Macau.

Portugal’s other vital contribution to Macau’s distinctiveness as a place to enjoy simple, good food has been its ability to create, and then satisfy, a market for anyone with a sweet tooth. Wherever we went round the busy streets of Macau itself or the two outlying islands of Taipa or Coloane (all now joined by bridges) there seemed to be pastry shops, cafes and bakeries, all distinguished by long and enthusiastic queues.

Rua do Cunha in Taipa was, I was informed, simply referred to as ‘the food street’ in which people waited to taste and then buy almond or peanut biscuits from the hugely popular Pasteleria Fong Koi and Pasteleria Koi Kei. Over on the much more verdant Coloane there was a justifiable queue outside Lord Stows Bakery, famous for its nata or Portuguese egg, a company which has now opened numerous branches across Asia. Back at the ferry terminal, we seemed conspicuous by the fact that we seemed to be the only people not carrying a large bag of biscuits from the Choi Heong Yuen Bakery.

There are swathes of Macau that with their casinos and neon lights do resemble the strip in Las Vegas, although I learnt that here the pawn shops are open 24 hours a day for those deserted by Lady Luck. But just beyond, in an area of only 30 sq kilometres, is a vast array of inexpensive and fascinating good food.

A Lorcha, Rua do Almirante Sergio 289, Macau, Tel 28313193,

Antonio, Rua dos Negociantes No 3, Taipa, Macau. www.antoniomacau.com

Pousada de Sao Tiago, a small hotel built out of a 17th century fortress, www.saotiago.com.mo

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,406 featured articles

- 274,929 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,406 featured articles

- 274,929 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes