Jeanne Vito is an Afropean wine entrepreneur brought up in Chablis, working and living between South Africa, Togo and Germany. She has recently founded VINO VITO*, a Togo-based educational wine platform for West Africans. She made her first vintage in South Africa but she says her destiny brought her back into the land of her ancestors to grow vines. Portrait by Audrey Mariani. See this guide to our recent South African coverage.

‘You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So, you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something – your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever.’

In any of us, there will be something of Steve Jobs’ approach that deeply resonates within us – something in our hearts and our souls, telling us that we are made of more than just thoughts, feelings or current life situations. My African spirituality has never let me down. It made all the difference in my life and it has led me, triggered by wine, to return to my forefathers’ land.

I am Jeanne Vito. My forename is from France where it was given to me. My family name is from Benin. I was born and raised in Chablis. Both my parents came from West Africa – cradle of Vodun.

I am Jeanne Vito. My skin is as black as that of my father, my mother and my three siblings. I grew up in a white wine region, on a white wine farm owned by a white family. In 2019, I made my first Pinot Noir on the Cape of Good Hope. I made it with the support of Zimbabwean, Tariro Masayiti, the first-ever non-white graduate in oenology at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, and of Hildegard Witbooi, the only Khoisan viticulturist and one of the few in the world who is female. And I just started my own vineyard in Togo.

I feel strongly connected to my ancestors – without ignoring my Burgundian side and my deep admiration for this particular French region, its culture and its splendid characters. But my roots are in Africa. Wine has taken me on a journey back to these roots, back to my forebears’ land. It has been a long way for me so far. And there is still a long walk ahead. Let me tell you my story up to now. Let me start from the very beginning. Step by step.

A Chablisienne youth

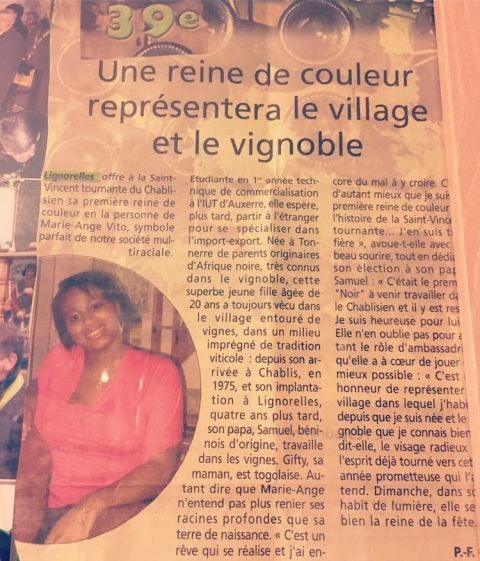

Although my father, Samuel Messan Vito, has a surname that sounds Italian, he is a member of the Fon people from Benin. In his late twenties, in 1968, he left his family home for a summer job in France. The universe brought him to Chablis. And, despite favouring big-city life until then, he instantly fell for this region. ‘It was love at first sight, it was real, juvenile love for the unknown; I had no clue about wine or terroir, but this colourful landscape of plantings in rows caught my spirit’, he says. What was initially supposed to be a temporary experience became the start of a 45-year working life in the Burgundian wine world. This was a time when his parents found the right wife for Samuel. So my mum, Gifty Essenam Ayawavi from Togo, was sent to him and gave birth to four children in the most rural countryside of France, in Lignorelles, a village of approximately 150 inhabitants, harbouring the only Black family in the small wine world of Chablis.

In those times, racism was present in nearly every aspect of our lives. For many locals, meeting with my family was their first encounter with Black people, which didn’t make my father’s work life easier. He was the butt of many jokes. ‘A Black in a Chardonnay vineyard – will the wines still be white?’

The truth is that my father tried not to care. Instead he escaped, with the vines as his companions. Vine-growing awakened his true nature, his true spiritual self. Since those days, he has never stopped seeing vineyards through the eyes of love, just like parents look at their children. Every time he opened a bottle of wine, he would spill the first drops on the floor opposite our ancestors’ gallery wall saying, ‘Cheers to our ancestors’. It was a way to honour them and to invite the spirits and stories of those who came before us into his wine universe. And it was a way for us kids not to break with the vines and the wines. I started drinking bourru (the region’s fermenting grape juice) with my dad at the age of eight. After daily school, I always joined my parents in the vineyard or cellar, living with the rhythm of nature and wine. It was a time when we kids would tread the grapes with our feet, a time when we harvested by hand, before machines took over in the late 1990s.

Transient escape

Looking back, I now realise how lucky I was to grow up in a wine domaine, wandering with my dad among vines. Dad was often talking, sometimes joking with them, giving them nicknames and even sharing his secrets with them. ‘Tell the vines what you want, and they will do the rest’, he liked telling me. To set up a winery in Togo was his dream, being whispered to his planted friends.

My dream at that time? While becoming a teenager and later a young adult, my intention grew to go far, very far from my rural surrounding, which I saw as a centre of closed-minded people. I hated the feeling of being different. I needed to escape to a place where my appearance would not be noticed. I hated to hear ‘because you are Black, your struggle will be double’, whether it was coming from my parents or from the community.

But there was another side to the dear country of my birth and its society. By chance, I was awarded a scholarship, thanks to Rotary International, to further my business studies in London. Those three years at Kingston University marked the beginning of a one-decade international professional career, working and living in European and Asian metropolises, mostly in Tokyo and two years in Paris until 2017, starting my own company coaching luxury hotel and restaurant staff in Japanese etiquette.

Eventual enlightenment

Funnily enough, I felt that the more successful I became, the smaller I was becoming. In fact, it seemed to me I was forgetting my identity. My encounter with the Shinto culture was my wake-up call: it showed me through ikigai (‘the reason for being’) that there must be a better and more fulfilling way to embrace life. Japan helped me to reconnect with my hidden ‘too shy and scared to be real’ passion for vine and wine and with my family’s origin. I deeply felt my ancestors trying to communicate, calling me back to Mother Africa. One morning it was clear: I have to follow my origin, and this has to do with wine. How? Why? I had no clue.

At nearly the same time, my father’s retirement was followed by his second stroke and, looking back on his life’s work with a mystic mix of frustration and confidence, he questioned why he had made all these efforts. It couldn’t have been for nothing. He felt there must be a bigger sense to it – larger, more infinite than just a life. He was right. I call it ‘legacy’.

This all resonated with me, to such an extent that in 2017 I made a complete turnaround. I came back to Burgundy, went back to school. I joined the Dijon-based Institut National Supérieur des Sciences Agronomique (Agrosup) for an advanced Master's in Wine Science and International Wine Trade to gain the necessary foundation for growing vines in Togo and setting up a winery there. Everyone called me crazy and criticised my ambition, but now it was my turn not to care. Besides, I could feel the presence of my ancestors through my Akua’ba necklace, honouring the West African divinity of fertility.

From Clemens Busch to Springfontein

In 2018, I had to carry out a 6-month internship abroad. Surprisingly, the universe first sent me to Germany, to Clemens Busch, a great biodynamic winery in the Mosel. Clemens, his wife Rita and even I couldn’t really understand the relevance to my Togolese project, but they decided to trust destiny and help me. After all, Togo and Germany have a historical link. While working in the steep Marienburg slopes, I found myself talking to vines like my father. And I shared with them that my ideal life partner would cross between Europe and Africa, linked to the wine industry, with great passion for its products, susceptible to my ancestors’ land and mature enough to let me pursue my family legacy in Togo.

Little did I know that my experience at Clemens Busch would change my life in exactly this way. There was a tasting event organised by Clemens and Rita for the winery of a close friend unknown to me. But suddenly I was sitting opposite Tariro Masayiti and Hildegard Witbooi. The former turned out to be, for nearly a decade now, cellarmaster of Springfontein, a wine estate that specialises in the indigenous South African grape varieties Pinotage and Chenel. The latter, his wife, with a Master's degree in horticulture, is managing the place’s organic agricultural activities. Because of its very particular terroir, WO Springfontein Rim has an appellation of its own.

The two spontaneously invited me for a vintage in the Cape.

Mami Wata Pinot Noir and Domaine Akua’ba

What I was not aware of was that my neighbour to the left at this special night’s table was Johst Weber, who started Springfontein from scratch 25 years ago. He, growing vines in a region which the South African wine establishment saw as impossible (‘you will make a good vinegar on those poor limestone soils under the cold ocean’s clouds’) and me, engaging myself in a project that hardly anyone could believe – we developed a sense of admiration for each other. Timidly we fell in love with each other. Unexpectedly but not accidentally. When I came to his house for the very first time, there was this huge batik of … Akua’ba that had hung on his entrance wall for the last 30 years.

With a good combination of difference and similarities, and the latter featuring the importance of legacy, our relationship extended to a higher spiritual level. We realised that we were destined to be in each other’s path, to bring encouragement in order to keep going on our earthly odyssey that we decided to call Afrodynamics. It’s what we are considering as a way of living with Mother Earth, a farming philosophy bringing African spiritual principles and practices into the heart of our life and work. Some people would say ‘it’s biodynamic, the African way’. But in reality, it’s more than that. We started doing some searches to better explain what we have called the ancestors’ way of living with crop plants and using them: vodun, traditions, knowledge and wisdom passed down over centuries and generations in agriculture. We still have a long way to go …

In 2019, I made my first wine, at Springfontein. Without the support of the estate team, a mix of beautiful Black, Cape coloured and white people, sometimes laughing about my very French oenological approach, I would never have been able to get this done. It’s – what else? – a Pinot Noir. A little too astringent, a little low in body and alcohol, but drinkable. So I have been told.

As of this year’s 2020 vintage, the second Mami Wata Pinot Noir has already been made. My father, now 80, joined the harvest in the Cape. I haven’t seen him dancing in the jolly, happy way he did in Springfontein’s Ulumbaza Wine Bar(n) for years.

In addition, we have also found the right land for vine-growing in Togo. The spot on the country’s high northern plateau is currently being prepared and should welcome its first vines in the coming year. Domaine Akua’ba, wine made in Africa primarily for anyone feeling connected to Mother Africa, is my premier intention. That’s the destination of my spiritual wine journey back to Africa.

The greatest treasures on this journey are the genuine friends and the beautiful souls I have encountered. They brought and continue to bring vibrant energy to the world. I also feel grateful for sharing the wine world’s deep sense of mutual co-operation. I hope my story will inspire people, bring them the courage to follow their intuition and the strength to follow their dream. It is never too late!

*The VINO VITO agency offers basic wine training for the local hospitality industry, developing wine confidence through knowledge as well as wine-service skills. They have recently extended their services to the local public via wine tastings and courses to learn the basics and simply buy wines. In addition, they have just started a social project in Kloto prefecture, setting up an agri-viticulture training centre for young female students.