Le Bernardin – piscine longevity

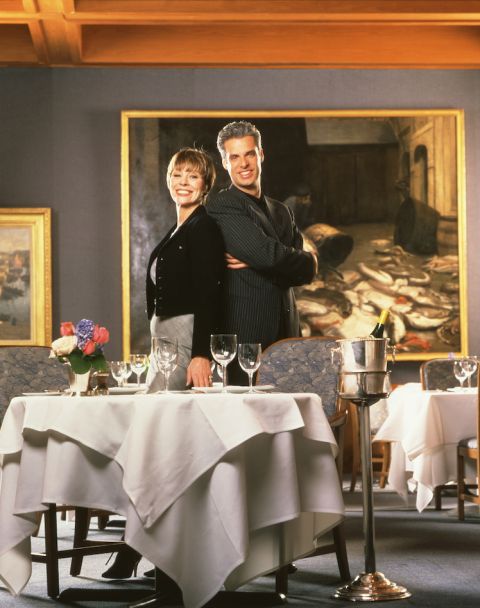

A toast to New York's doyenne of restaurateurs, please. Above she's seen with her brother Gilbert when they worked together in Paris.

Next week, 78-year-old Maguy Le Coze celebrates a historic landmark in the restaurant business. Next Wednesday 9 November a special dinner will be held at her restaurant, Le Bernardin in New York, to mark the 50th anniversary of when it served one of its characteristic fish dishes to its very first customer.

That was just over 3,600 miles away to the east on the Quai de la Tournelle close to the River Seine in Paris, where Maguy and her brother Gilbert had just opened Le Bernardin in 1972. Obviously extremely close, brother and sister had made a promise to each other to leave the family seaside hotel on the coast of Brittany for Paris when she turned 18. They pooled their savings with loans from friends, an uncle, their parents and a friendly bank manager to open their first restaurant with a name borrowed from a song their father used to sing to them as children.

That the Le Cozes chose to name their restaurant after a song – rather than after themselves – is one of the few remaining throwbacks to the era in which they opened. This was before chefs became stars, a time when none would have considered themselves important enough to choose their own name for their restaurant. Michel Guérard was cooking at Le Pot au Feu; Alain Senderens was at Archestrate; and, even later, Joël Robuchon’s Paris restaurant was called Jamin, long before he opened the first branch of L’Atelier du Robuchon. Chefs, at that time, stayed in their kitchens.

In those years, there was no question that France was the undisputed epicentre of everything that was exciting about restaurants and the Le Cozes’ concentration on fish provided a focus and generated considerable excitement. By the early 1980s they had outgrown their initial location and moved Le Bernardin to a considerably larger and plusher spot near the Champs-Élysées, where they began to attract an international clientele comprised particularly of Americans.

These included famous American gastronomes James Beard and R W Apple Jr of the New York Times and it was then that the idea of opening in New York began to preoccupy Maguy, who started to collect business cards for the time when she would open her restaurant over there. But her brother was less enthusiastic, an attitude not helped by a visit to New York in 1983 where he found an absence of top-quality fish and a plethora of seemingly ubiquitous iceberg lettuce.

This apparently intractable situation – of a sister keen to move and a brother determined not to – was finally resolved by a property developer. Ben Holloway was then chairman of Equitable Life, and keen to develop what was to be the new Equitable Centre. A deal was struck in his apartment overlooking the Eiffel Tower over a bottle of Dom Pérignon and the Le Cozes were now the owners of a new 1,100-m2 (11,840-ft2) site in midtown Manhattan that has been Maguy’s professional home for the past 36 years.

Having initially been lukewarm about their new home, Gilbert was soon convinced, and both focused all their attention on New York. To their cost. When Maguy heard that a cheque from Le Bernardin in Paris had bounced, she hurried back to find that their bookkeeper had been stealing to great effect – and had quickly vanished. Somewhat reluctantly, they decided to sell up in Paris and concentrate on New York.

Worse was to follow. In 1994 while working out, Gilbert suffered a fatal heart attack, aged 49.

I interviewed Maguy in 2011 for my first book The Art of The Restaurateur, in which I describe her as charming, glamorous and equally authoritative. Recounting the effect of her brother’s sudden death during our encounter, she sighed before saying, ‘Nobody expected Le Bernardin to survive, except me. I took a month off, put some colour in my cheeks and said to myself that the show must go on.’ It was considering this period, when she had just lost the person with whom she had embarked on this transatlantic venture, that prompted her at the end to comment, ‘Being a restaurateur is a very worthwhile career, but every young person must think twice before embarking on it.’ Sound advice.

The Le Cozes acted wisely to ensure longevity. In 1994, just before Gilbert’s premature death, they hired the young Eric Ripert, born in France but who had moved to the US after stints under Robuchon and Jean-Louis Palladin as head chef, with Gilbert realising perhaps that he could not evolve professionally any further. Since then, Ripert has become the face of Le Bernardin, his accent and his looks contributing to his success with the media. The partnership of Ripert and Le Coze has been based on a simple principle: if one partner disagrees, then they simply do not proceed, whatever the issue may be.

Then in 2007, Maguy hired Aldo Sohm, a young Austrian sommelier who had applied for a job at Le Bernardin and is surely one of the longest-serving somms in a city which seems to operate a constant carousel of hospitality employers and employees. He explains,‘I worked in a smaller restaurant in the city (until I got settled in NY) but knew I had to transition to a high-calibre restaurant eventually and when the opportunity to interview at Le Bernardin came about I took the opportunity. Maguy was sitting with the general manager in my first interview and I found her very impressive. I wanted to work in a great team and I found my home with two very special people, Maguy and Eric, and of course the rest of the Le Bernardin team.’ The chemistry has worked so well that in 2014 together they opened the more relaxed and informal Aldo Sohm Wine Bar next door.

The principal reason for Le Bernardin’s, and Maguy’s, longevity lies, however, in the produce they have concentrated on since day one: fish. I have written elsewhere about how London’s most long-lived restaurants all began by selling fish and some have prospered since the mid 19th century. The current Le Bernardin may be located in New York but it has never lost the connection to its Brittany roots: a portrait of Maguy’s grandfather in his fishing outfit still overlooks the bar.

In 2011 Maguy explained to me how they were serving raw fish long before Nobu. ‘It’s part of the Breton repertoire but early on my American clients were reluctant to try it so I used to have to say to them “Order it, and if you don’t like it I will replace it with another dish free of charge.”’ One dish from her late brother’s repertoire, of two sea urchins, one raw, the other barely cooked with warm butter, is a dish I would definitely recommend.

And then there has been the growth in the perceived health-giving attributes of a diet based on eating fish, which has led to an increase in Le Bernardin’s customers. As Le Coze explained when I saw her in 2011, ‘This is particularly the case at the moment, and this comes as a surprise to me, when the age of our customers has never been so young, especially in the evening and predominantly wealthy Asians.’

The lure of the health-giving properties of Le Bernardin’s fish-based menu must take some of the credit. But, in my opinion, the unflinching standards of Maguy Le Coze are equally important.

À votre santé, Maguy!

Le Bernardin 787 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10019; tel: +1-212-554-1515

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,423 featured articles

- 274,424 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,423 featured articles

- 274,424 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes