The confluence of International Women’s Day yesterday and the British version of Mother’s Day tomorrow made me think yet again of my late mother and the multiple influences she has had on me and my life.

This made me think about mothers in general and I decided it would be fascinating to ask six leading chefs, all of whom I admire in different respects, to reflect on their own mothers and the culinary influences which they may have – or may not have – inherited from them.

I asked only male chefs because I feel mother/son relationships (and father/daughter relationships) are the most fascinating. Also, mothers tend to rule domestic kitchens anyway.

I began by explaining my own mother’s culinary influence, greater even than her ability to roast meat, poach salmon and make chopped and fried fish as well as gefilte fish. She also had a particular love of Middle Eastern cooking.

It was her maxim ‘to taste before you season’. She would quote this every family dinner which invariably began with soup: often chicken, pea or tomato with rice. My father would be served first and would automatically reach for the salt and pepper before he’d had a single mouthful. I lost count of the times she threatened, ‘Len, one day I’ll put so much seasoning in the soup that it’ll make you sick.’ Needless to say, she never did.

But I never forgot. When cooking, taste before you season.

Miles Kirby, one of the three New Zealand founders of Caravan restaurants in London and the creator of their menus.

My mother, pictured below, is a great cook and always made mealtimes an event.

The greatest culinary gift my mother gave me was curiosity and understanding of flavour. She would collect recipes and build scrapbooks of anything interesting and ‘different’. I vividly remember at the age of five or six commenting on my dislike for caraway seeds and hoisin sauce. Even knowing what these ingredients were was beyond the understanding of my peers who were still deciding between peanut butter or Vegemite in their sandwiches for school lunch. For the record I grew to love both caraway and hoisin through the constant gentle pressure of sustained exposure to those ingredients. Now I can’t imagine a world without them.

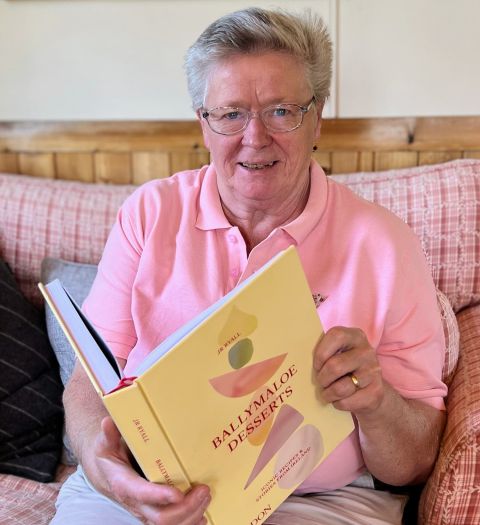

J R Ryall, the Irish dessert supremo at Ballymaloe House hotel outside Cork in Ireland.

My mother cooked simple fresh meals every day. Her repertoire contained mostly traditional dishes – nothing fussy! Our home was always busy with unannounced daily visitors, who mostly arrived around mealtimes. Mum liked the table to be set properly before we all sat down to eat and there was always enough in the pot to feed everyone. From her, I learnt that it is best to cook for more people than you expect, and that even a simple boiled egg supper can become something special at a nicely set table.

Isaac McHale, the Scottish founder of London’s The Clove Club.

I loved baking with my mum when I was four or five years old. We used the Dairy Cookbook, a Scottish staple, to make pancakes (crêpes), pancakes (Scottish drop scones cooked on a girdle, a Scottish cast-iron griddle), macaroons and more. I loved it – a mixture of creating something delicious from flour and dairy felt magical, and the instant feedback of making people happy through cooking. My mum cooked simple food, always from scratch. Be it breaded fish, mackerel in oatmeal, curries or more, it was always from scratch. I remember making breadcrumbs from stale bread to coat fish for pan-frying for dinner, and lots more. By the age of six or seven I was fascinated by pakora, the fritter from the Indian subcontinent, that we would have as a treat from the Pakistani or Punjabi takeaways of Glasgow. It was my confidence in the kitchen with my mum that made me want to learn how to make pakora myself, and which led me down the path of becoming a chef.

Shaun Hill, born in Northern Ireland, and the chef/proprietor of The Walnut Tree Inn, Llanddewi Skirrid, near Abergavenny, Wales.

My mother made excellent potato bread and soda bread, Ulster specialties. Her main ambition in most cookery though was to make sure whatever she was making was completely and thoroughly cooked through, so chickens and legs of lamb were fairly dried out but did yield decent gravy. Cakes were gasping for breath and best avoided. My father never quite understood all this as he put a large dollop of English mustard next to everything anyway. He would go to Soho and Fitzrovia in London and return with live eels from Hamburger Stores fish shop in Brewer Street or snails from Schmidts in Charlotte Street, all of which were worrying prospects for her. If they were entertaining, the solution was to take the guests to the pub so that they were really hungry and a touch disoriented by the time food was served. She was a very appreciative and loyal eater of whatever I made however and would say how delicious she thought it all was before the spoon or fork neared her mouth. Not a great gourmet then, nor a great cook but still a great mother. And the bread was fine.

Shaun Searley, chef at The Quality Chop House in London.

From an early age my mother taught me to be resourceful with ingredients: for example saving the dripping from the Sunday roast beef in a cleaned-out baked beans tin, to be used for the following week’s spuds.

She didn’t have many recipes written down but two notable recipes were for a proper steak and kidney pie (although I didn’t care much for this at that age). But I loved the smell of it cooking plus it was from a recipe that her mother used to make. The other is her famous turkey soup the day after Boxing Day. Originally made from the carcass of the Christmas Day roast, again this was more a utilisation of leftovers. However, these days the family is so big that one carcass won’t do the business so she buys a whole extra turkey just for soup!

Finally, on a nostalgic note, Neil Forbes of Edinburgh’s Cafe St Honoré reminisces about his late mother.

If I close my eyes real tight, I can hear the sound my mother’s wedding ring clink against the side of the earthenware mixing bowl, my wee nose peeking over the edge of the bunker, as we call a work surface, while she would make scones, mixing the flour with the butter to make all sorts, rock cakes or the best shortbread ever. It wasn’t crisp and biscuit-like; it was a soft texture and chewy, like a brownie from the fridge, and about an inch thick, with lashings of sugar on top, just what Santa loved on Christmas Eve, cut in to fingers.

But if my wonderful mother were alive now, I would ask her to make me a rice pudding, a proper one with skin on top, served at the table, family-style, sweet and packed full of exploded grains of rice which soak up the sweetened milk and cream. A fight with my brothers to steal the skin on top will always make me smile. Sometimes a dollop of jam, usually raspberry, was added as a break in the richness – just simple, wonderful cookery.

Another dish which was very welcome when my mother and my Gran would come to Cub or Scout camp to cheer us up, was a coconut tart, again with jam as a layer. Think macaroon, almost frangipane-like, but soft and sweet and exotic, as coconut was seen back in the 1970s. The pastry was perfect, and not too fine, but sweet. My fellow patrol members and I devoured it in seconds. Even Akela approved.

And as a Scottish family, the steam sponge pudding was ever so popular. It seemed as though there was always a pot on the stove with an upside-down saucer in it, with water bubbling away. A particularly well-worn old crochet or knitted hat, probably made of rope or string, was used to house the pudding basin, suspended from each pot handle. It was nearly always served with jam again – us Scots love our jam – but sometimes golden syrup, and devoured with jugs of custard. Ah, the memories! And to be perfectly honest, of all the fancy pastry chefs that I have worked with, no one comes close to what my dear old mum would make.