From 3,180 Hungarian forints, €10.50, 11.40 Swiss francs, £12.95, $17.99

The very large Meinklang family farm in Burgenland, right on the Hungarian border, is pretty remarkable. It’s not the typical commercial enterprise one would expect from an operation of that size. The entire 2,000 hectares (4,940 acres) are certified organic and biodynamic (since 2002) and run as a seamless permaculture biome, complete with pasture-raised Aubrac and Angus cattle, rare-breed Pannonian Mangalitza pigs, horses, sheep, chickens, apple orchards and ancient varieties of spelt, oats, rye, winter and summer barley, winter and summer durum wheat, millet, corn and buckwheat. They’ve established the first holistic Demeter-certified brewery where they make beer from their ancient grain varieties. And, of course, they’re winegrowers. The farm supports the entire Michlits family, each of the three sons responsible for a different area: Hannes (above) and Lukas (below) have developed the farming towards ancient grains, unirrigated cropping and hardy, well-adapted, pasture-raised livestock. They also make apple juice, vinegar, brandy and their own speciality flour. Werner and his wife Angela (pictured at the top of this page in their unpruned Grauburgunder vineyard) run the wine side of things with Niklas Peltzer making the wine.

Their 55 ha (135 acres) of Demeter-certified vineyards are managed, quite literally and (I argue for reasons explained below) uniquely, as a biotope. Alongside all the usual practices of biodynamic viticulture – native cover crops, composted manure and green waste from their own farm to feed the soil, plant species that encourage natural biodiversity – they have introduced something that I have never come across before.

In their largest vineyard (of 10 ha/25 acres) they have created 27 eco-islands, taking up roughly 800 sq m (8,600 sq ft) of what was once vines and breaking up the vine rows. Each eco-island is shaped like a giant water droplet and is centred around a fruit or nut tree (almond, apple, quince, plum). Here they encourage the growth of wild fruit, vegetables, shrubs, wild flowers and grasses, herbs and even weeds such as thistles and nettles which are an important food source and habitat for specific insects. The trees and eco-islands provide habitats for birds, field mice, shrews, hedgehogs, stone martens and rare dormice. They’ve also planted elderberry bushes as the fruit is a natural food source for over 62 species of birds. This is Nature’s answer to nesting boxes and insect hotels.

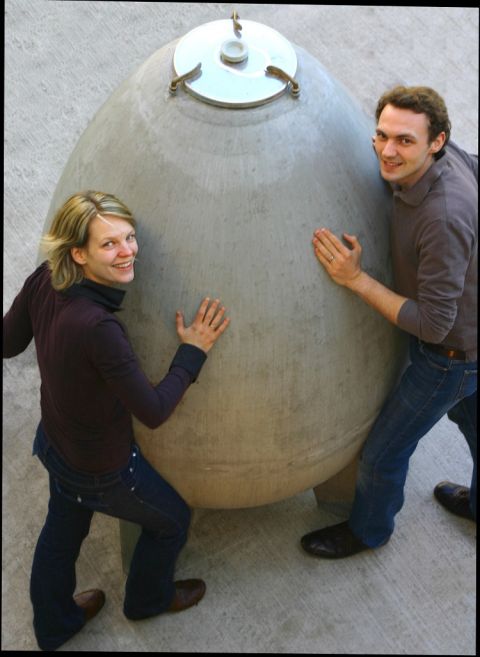

The winemaking at Meinklang is equally earth-centred. Fermentation is all spontaneous and malolactic conversion also happens naturally, in its own time. They don’t fine and they vinify with very little to zero sulphite additions. Most of the wine movement is by gravity rather than pumping. They use a mix of stainless steel, wood and concrete eggs for vinification and ageing. It’s natural wine, but made in a spotlessly clean environment. Wild but not whacky.

If I could, I’d recommend their entire range of wines. I bought a box of six from Vintage Roots, including their Gruner Veltliner, Graupert Pinot Gris (from a vineyard that is unpruned), Weisser Mulatschak, Roter Mulatschak, Prosa Rosé Frizzante and Pinot Noir. Every wine tasted fantastic and every one of them was extremely good value (only the Graupert was more than £14.50).

But my wine of the week is the one that made me laugh out loud, with sheer delight, when I tasted it.

The Roter Mulatschak is a red, very lightly sparkling wine (the fizz doesn't hang around too long, leaving a sense of electric current rather than bubbles) made from 50% Zweigelt and 50% St Laurent from Neusiedlersee, bottled under crown cap. The grapes were picked early, but ripe, at the beginning of September and were co-fermented for four days on skin and stems. The wine was then whole-bunch pressed and spent another four months on fine lees. Alcohol is less than 11.5%, total acidity is 5.9 g/l, and residual sugar is 1 g/l. It's unfiltered.

I described it as cherry and bramble-berry juice with a sorrel-leaf tang with green-coffee-bean and box-hedge streaks through punky, Andy-Warhol-bold-sassed purple fruit. I’d stuck it in the fridge for half an hour before tasting it for the first time, and while still cold it tasted of street art (red, purple, black splashed across bricks, sidewalks, rooftops). ‘Krumping!’ I wrote, unable to think of a single other word to describe the phenomenal, untrammelled, mesmerising energy of this little wine. As it warmed up in the glass and bottle, it tasted like ragtime jazz, like the sweet melody of maraschino cherry, playing louder and more insistently, building charm into the finish. ‘I could’, I scrawled in my notebook, ‘drink this every day of my life!’

Over the weekend, we tried it several times: home-made burgers on Friday night, Thomasina Miers’ celeriac maltagliati with romesco sauce (with double the chillis in the recipe!) for Saturday lunch, with Anna Jones’ roast pumpkin and pistachio gremolata, white-vermouth-and-Dijon-mustard-poached smoked haddock, and with our Goan friend’s pork sorpotel (cooked for four days!). No matter what we tried it with, it worked. The almost invisible tannins meant that it was as juicy cold as it was at room temperature and happily complicit in the sins of lunchtime drinking (light enough alcohol, I reasoned, to justify consumption – not that I ever feel guilty about lunchtime wine…) and of pairing red wine with fish. It tasted good with red meat, chilli heat, sweet root veg, smoke and mustard, garlic and even ketchup. It would be the perfect brunch wine, comfortably bridging the hearty home flavours of a full English for traditional palates and the fusion spice-and-spinach flavours of modern brunch dishes.

More than anything else, it has some of that kick-ass energy that all of us, weary of COVID-19, lockdown and winter, could do with by the bucketload. You could drink this over the next couple of years, but I defy you to keep it longer than a week. And it’s a mere £12.95 – a snip for bottled joy.

The wine is available in Hungary, Austria, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium, the UK and the USA (CA, NY, TN, PA, CT, FL). I bought my bottle from Vintage Roots in Hampshire. The 2019 (which I fully intend to taste when it eventually steers its way through post-Brexit bureaucracy to land on English soil) is also widely available, and if you’re in Norway, that’s the vintage that Nos Dos has in stock for 189.90 kroner.