1 December Our Throwback Thursday features a double helping today, one article about Nick's new book below and another about my new £4.99 wine primer from Penguin. Both would make great gifts – along with membership of JancisRobinson.com, of course.

29 October Today the Financial Times publishes extracts from Nick's new book On The Menu (£30 Unbound/Random House), a beautifully illustrated consideration of what he calls 'the world's favourite piece of paper'. The book, with its 80 iconic menus and interviews with 14 great chefs from around the world, examines the history, design, conception, implementation, legal aspects and development of this hugely significant document.

The menu is the single piece of paper that gives the world the most pleasure. To date, nobody has successfully challenged me when presented with this bold statement. And neither have I persuaded myself otherwise.

Bank statements are only cheering if you are in credit. A peace treaty implies that one side has lost. A marriage certificate or birth certificate is examined only on rare occasions. And, of course, in a few years’ time these sorts of documents might not exist in a physical form at all, as they all inevitably will be digitised.

Menus do appear on the internet – although I try never to look at them before going to any restaurant so as not to spoil the surprise – but they will have to continue in a physical form as they are a vital ingredient in the make-up of every restaurant, one of the very few businesses that can never move entirely into cyberspace.

Indeed, a very common reaction from those I have spoken to about my new book On the Menu has been: ‘I wish you had told me a few weeks ago. I had an enormous pile of old menus which I’ve only just thrown out.’ Further proof that menus fulfil a role no other single piece of paper can match as a memento of a celebration or an exceptionally good meal.

Certain menus remain the closest we can get to what it must have been like to live through the Siege of Paris in 1870, for example, or to face the havoc about to be inflicted on your profession as a restaurateur in the US on the eve of Prohibition in 1920.

The slow evolution of the menu since it first appeared in the Parisian restaurants of the early 19th century is a remarkable thing. It’s a wonderful way to travel across time and place, to look through the menus of grand brasseries or of the first modern-minded English restaurants in the 20th century.

But as with anything there are improvements still to be made, in imagination and design, that will give the world’s restaurant-goers even greater pleasure. As long as we have the appetite, the menu is here to stay.

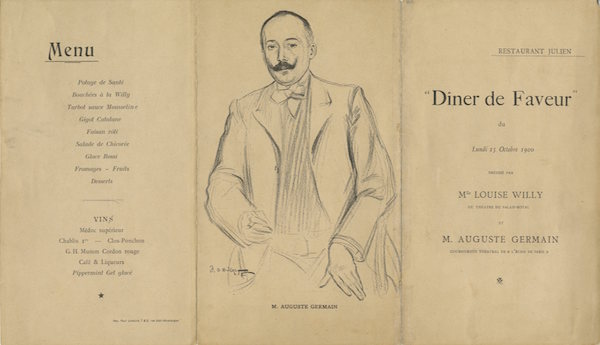

Illustrated here are both sides of a 1900 menu for a 'diner de faveur' from Paris’s Restaurant Julien.

Extract: Massimo Bottura on menus at the world-famous Osteria Francescana

Massimo Bottura agreed to meet and talk menus with me at 6 pm on a Saturday evening in the Champagne Room of the Connaught Hotel, Mayfair, London, because there they make the very best Bloody Mary, in his opinion. What emerged was an impressive, tall drink, and I could not help but notice that the green of the celery and the dark red of the vodka and tomato juice represented the colours of the Italian flag. Did Bottura know this already? Was he being funny, ironic – or simply patriotic?

He is, after all, all of these things, as anyone who calls his book Never Trust a Skinny Italian Chef surely has to be. Bottura has achieved fame since opening Osteria Francescana in Modena in 1995. Subsequently, he opened a second restaurant in Modena and one in Istanbul, and ran an admirable soup kitchen during Expo Milan 2015. He is also a chef, perhaps the chef, who most ably shows the vibrancy, artistic potential and sheer fun of a menu. It is impossible not to be excited as his large-format, four-page number unfolds.

The print is extremely clear, a simple grey font on a white background. Then a journey begins that takes the customer from the aperitivi in the top left-hand corner to the final flap with Proust’s famous quote – about the effect of a morsel of madeleine in a spoonful of tea – above a large, colourful pizza napoletana with the signature of the artist, Giuliano della Casa, and the date.

En route, Bottura takes us to Langhirano for 36-month-aged prosciutto; from Boston, USA, to Hokkaido, Japan, by way of Goro, a town by the mouth of the Po in Emilia-Romagna, for his crab dish; to his native Modena for its rare 44-year-old balsamic vinegar; and finally up the river where the eel for another dish once swam. Watercolours of a lobster, the outline of Vesuvius above the word Napoli and the name of Georges Cogny (the French chef to whom Bottura was once apprenticed) accompanied by a heart, also grace the page. No fewer than nine tortellini, the dish cooked by his grandmother that excited Bottura’s palate as a boy, hover above the seven other pasta courses – because, as he said, they are always floating in his mind. There is intrigue too: what is the 'crunchy' part of the lasagne, or veal 'not flame grilled'? And how could one not order a dessert described as 'Oops! I dropped the lemon tart'?

Bottura’s menu has to be as large as this to accommodate not just the many dishes he and his team create, but also how he thinks about writing his menus. 'There are several layers that may help you understand. There is my brain, how I think about food. Then there is my culture, as a citizen of Emilia-Romagna and of Italy. There is my conscience, my fight for a fairer world. Then there is my sense of responsibility, not just as a chef but also as an employer, a husband and a father. These factors combine to shape my point of view when it comes to writing our menus, and often I have to reset my brain to accommodate all of them.'

It is the tension between Emilia-Romagna and Italy that is most obvious. Bottura has managed to achieve for his country what his friends René Redzepi and Heston Blumenthal have done for Denmark and England respectively. He has arguably done for Italy what Ferran Adrià did for Spain, but in certain respects his task has been even trickier. The reputation of the other three countries’ cooking was hardly glorious before these chefs emerged, whereas Italian food has been popular for decades.

And within Italy there has been a reluctance to change. 'Every Italian believes that their family makes a magic sauce and the perfect pasta. There is an inbuilt nostalgia that goes back to our walled cities,' he explains. 'There is a rigidity that is very difficult to change, but that is what I am trying to do.' As I listen, I am conscious that Bottura’s latest menu is only a work in progress, although he does add that with each one this brain-crunching becomes more and more difficult. 'The words get harder and harder,' he sighs.

The person responsible for allowing Bottura to reach this stage is his American-born wife Lara, whom he met while working in a New York kitchen, and whom he cites as his inspiration. 'She is not afraid to be critical but most importantly she is never nostalgic. She makes me think, and when that happens two people are always more effective than one.' Hence his now-famous dish 'Tortellini walking on broth': half a dozen tortellini fixed to a bowl with gelatin so that when hot broth is added they appear 'to walk as Christ once did on the water. I like this dish because it allows my customers to stop and think and not to lose themselves completely in everyday life,' Bottura explains.

And it was something as simple as the tortellini that allowed Bottura to give three very diferent examples of what still excites him about writing menus. The first was pretty basic: judging the quality and quantity of the prosciutto, mortadella and parmesan so that the umami level was absolutely correct in the pasta shells. The second was the joy in his voice as he recalled how two producers of bufalo mozzarella from Naples had recently come to show him their cheese and how he had found the quality so amazing that he felt compelled to create a new dessert involving the sour cherries of Modena especially for them.

Finally, perhaps when the Bloody Mary had worked its magic, he started to describe another dessert he was working on. 'Red Camouflage' incorporates smoked chocolate, has the brown-green colouring of a jugged hare, and is a savoury dish that takes its name from Andy Warhol’s painting Camouflage. Even Bottura admitted it sounded crazy.