'Overstuffed' wines analysed

A Purple Pager asked Elaine a question after her recent account of a vertical of Corison Kronos and the answer is surely interesting enough to share.

Peggy Baudon wrote:

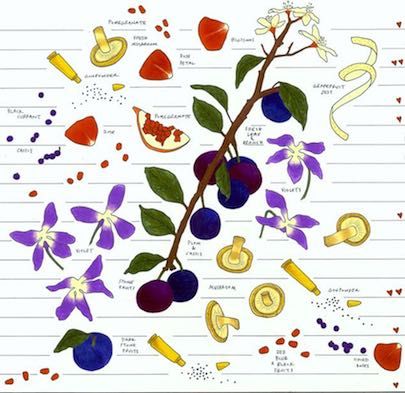

I absolutely loved the article about your vertical tasting of Corison's wines. The tasting visual (see right) is a beautiful representation of the evolution of the wines.

I have a question about your paragraph describing some wines coming out of California as having a sense of 'compression and compaction' despite being picked early but not having the overt ripeness and alcohol of many other wines. I have been contemplating this type of character in wines I've been tasting from right bank Bordeaux and have been trying to:

a. accurately express the character of the wine and

b. determine what vinification processes are being used to achieve such results.

As a description of this type of 'stuffed' wine I certainly appreciated your analogy of stuffing as much as possible into a rucksack. When I taste such a wine, I often feel a bit claustrophobic, as though I am also being stuffed into the glass with no air to breathe. It was a relief to read such an astute description of this type of wine style.

As a wine student though, I have not ascertained the vinification process/es that have contributed to this style. I wonder if you might have some information or feedback about vinification processes that may be used in California to achieve this effect in wine (or even in France). Thus far, I have narrowed down my guesses to reverse osmosis and vacuum distillation as ways to reduce water content in the must/wine and therefore leaving more 'stuff' in the wine (and therefore less 'space' and making it 'feel oppressive on the palate' as you eloquently described). However, I am also wondering if flash détente or thermovinification might have an additional hand in the process/es. It has been difficult to find information on the vinification of these types of wines – not surprisingly since they can be described as a 'trick' to adjust the wine unnaturally. Not many winemakers would wish to be called out in such a way.

Any feedback or guidance about vinification methods to achieve these effects in wine would be so greatly appreciated!

Elaine Chukan Brown replied:

Thank you so much for your kind email. I am so happy to read that you appreciated the article and that that description of the wine style made sense to you. I've been confronted by that sort of 'overstuffed' wine repeatedly and had spent time thinking through how to explain the experience of tasting them. It is good to know that the description of the overstuffed rucksack I used obviously made sense to you with your own tasting experience.

In terms of how such wines are made, I can offer explanations on a few possible cellar choices that might help give some perspective. Of course there would be variations on which techniques are used depending on particular wines but here are some thoughts that could help with the overall picture. More technical information can be found in the Oxford Companion (see, for example, the links below). Here I will try to describe the effect the techniques have on my tasting experience of the final wines.

In Bordeaux actually I was able to spend time speaking with producers who use flash détente or another form of thermovinification. There is some use of these methods in California as well but producers do what they can to avoid any conversation about them and from what I can tell they are used only by rather large-scale producers. I think that is or at least used to be true in Bordeaux as well – that those techniques tended to correlate with larger-volume producers, or the co-ops who have an obligation to make whatever fruit they get from their growers work for wine. My experience with flash détente and thermovinification more generally is that they are actually used to correct issues around under- or uneven ripeness, and around mould or mildew. There is flash détente and then there is also a kind of grape jacuzzi type process where the fruit is soaked in warm juice. I can't think of what the warm-juice method is actually called – and it has a different name in Bordeaux than in English. [For a discussion of methods and terminology in Beaujolais, see Beaujolais mapped and sipped – JH]

My understanding is that the warm-juice method works well for situations where fruit comes in with adequate sugars but something like underripe skins where the tannin would end up too hard and the hardness of the skins would lead to underripe flavours, perhaps in a cold year, for example. By essentially soaking the fruit immediately after harvest in a warm bath of juice for around 12 hours or so the skins are softened by the end of the soak. The fruit is then pressed off and fermented as normal. For larger-scale wineries there is equipment available just for this warm-juice method but I have seen smaller-scale wineries do it even just in a drain pan. It helps soften the tannin and shift the flavour a bit as well. It also helps to extract some of the colour from the skins to assist in binding anthocyanin to tannin later (part of how it softens the tannin) and make a darker wine. Underripe grapes otherwise often make lighter wine.

Flash détente is a specific technique that requires equipment just for that purpose. It is done at the must stage when grapes have been destemmed and possibly crushed and have not yet started to ferment. The must is quickly heated and then quickly cooled again. The rapid heating and then cooling causes colour release as well as aromatic release from the cells in the grape skins, and it also creates grape vapour. The vapour is sometimes captured and recompressed and added back to the must and sometimes not. If it is not, the juice is thus more concentrated. Sometimes the must is pressed and the juice is fermented like a white wine. Essentially flash détente is used for cases where the fruit comes in underripe or with uneven ripeness, again like in a cold year. Part of the trouble with underripe fruit is that the aromatic precursors are sort of locked up in the still-hard grape skin, as is the potential colour. Flash détente blasts open the cells and releases these aromatics and the colour thus making them available to the wine. It also helps avoid issues with underripe fruit flavours. Part of the difference between flash détente and the grape-bath method comes down to mould or mildew. If you have any fruit rot or mildew issues you would not put them in the bath but could use flash détente to 'dry' the grapes out, so to speak. In reality the flash détente is not drying the grapes as much as changing the composition of the enzymes that occur with mould or mildew so that they are no longer a problem.

However, I don't think any of the thermovinification techniques would be adequate to explain the compaction experience we're talking about in wine, though maybe you could use flash détente to get a big part of the way there on already ripe fruit. People here in California do seem to use flash détente to darken flavours and make a wine more intense without making it bigger, but they seem to be doing that more on high-volume 'supermarket wine' than on small-production boutique ($100+) wines. In Bordeaux I do believe there is a legitimate need for flash détente or the grape-bath method in particularly cold years, and again especially in co-ops where they need to make use of all of their grapes regardless of their condition. In California, however, some producers seem to be using flash détente just to intensify already-ripe fruit. Again, I have only seen this done for rather high volume wines.

With Bordeaux varieties racking plays an important role in the mouthfeel of the wine. Producers who want more of what I call an 'open weave' mouthfeel tend to have racked less. There is a style of Bordeaux racking that is intentionally introducing oxygen at key stages in the ageing process and thus changing the feel of the wine across the palate. It seems to sort of thicken the weave of the wine and make the wine more opaque in the mouth, if that makes sense. Again, I don't think that alone would account for the feeling of stuffing full the rucksack, but it does change the sense of openness of the wine from what I have experienced, creating a fuller, less open weave to the wine. It doesn't make the wine significantly more dense though. So, it is more like changing the weave of the fabric but not like adding more layers of fabric, if you see what I mean.

I think a big part of what is behind the trend I described seeing here in Napa with that overstuffed rucksack is actually coming largely from extended maceration. Producers now frequently leave the wine on skins long after fermentation is complete. So fermentation can readily be done in something like seven to 10 days, depending on various conditions, and yet producers will leave the wine on grape skins for longer to extract more colour and tannin from the skins. If you taste the wine through its time on skins, you can feel the tannin character and mouthfeel of the wine change significantly. The mouthfeel gets plusher and smoother (more like sheered velvet) over time, and the overall experience of the wine also gets denser on the palate as though there is simply more matter in the glass.

The extraction happening during extended maceration is different from than that during fermentation itself in that during fermentation producers are doing regular pump-overs or punch-downs in order to manually draw more actual matter out of the pomace of the grape. During extended maceration they are doing less manual extraction and instead soaking the pomace more like leaving a tea bag in hot water for longer. So, you are not pulling chunky matter out as much in this extended period but you are definitely intensifying everything. Also, since extended maceration is a much gentler soak without the manual extraction of active punch-downs, the seeds are not an issue during this time. During active fermentation there can be a worry of extracting too much astringency or harsh tannin from the seeds. This worry essentially is no longer there during extended maceration. Generally the seeds will have also fallen to the bottom of the tank or fermentation vessel by then.

In some cases the initial tannin extraction at the end of and just after fermentation can get more astringent in the early stages of extended maceration. When that happens though the idea is for the producer to just keep going with the extended maceration as after this initial period of increased astringency or bitterness the desired smoothness will appear. So, in some cases (it depends on the variety, the vintage conditions, and other aspects of the cellar) extended maceration will simply need to be longer in order to help resolve the tannin and smooth the mouthfeel beyond this initial period of bitterness.

The extended maceration period also changes the shape of the wine and the way it feels in the mouth – the mouthfeel gets plusher and smoother, the wine gets denser and what I think of as more opaque in the mouth – like the fabric of the wine becomes completely dark and solid. It feels like it goes from being transparent, as though there is room in it to see through, to being opaque, as though light cannot pass through. How dense and opaque the wine becomes depends largely on how long the extended maceration is done. Generally it is more common now to see producers doing something like 2–4 weeks extended maceration. With that length of time a wine will develop a significantly smoother mouthfeel, and a more filled-in weave while building some sense of additional density but not a ton. As it has become more common to drink wines young, producers have also had to find ways to make tannin in high-tannin wines like those from Bordeaux varieties more approachable. Some extended maceration has proven one way to do this.

Depending on the length of the extended maceration, and also on how things like racking are handled later, the wine can also start to feel denser, as I was describing. For me, wines that have gone through really significant extended maceration feel like putting black velvet in my mouth, if that makes sense – black velvet sort of absorbs all the light, you can't see through it, and it feels plush to the touch. The way it absorbs the light also makes it a richer black than something like black silk would be. You could even think of it as if a Cabernet Sauvignon from a warmer site could be picked early and so have good fresh acidity but because the site is warmer it would also give black fruit flavours. Now, if the winemaker ferments it and leaves it on skins just a few days after fermentation, she makes a wine like black silk from that site. If she does extended maceration, over time it becomes more and more like black velvet. The longer the time on skins, the thicker the pile of the velvet. I have seen producers leave Bordeaux varieties here on skins as much as 30, 45, and even 80+ days. The much longer extended maceration wines to me also tend to feel like they have lost freshness even if they still have good acidity.

When making red wines winemakers can also choose to concentrate the structure, flavours, and colour of a wine by bleeding off some of the initial juice soon after crushing the wine. This juice that is removed can also be used to make a saignée-method rosé if desired. Draining off some of the juice before fermentation starts effectively intensifies the various aspects of the wine by simply changing the skin to juice ratio of the fermentation. Since there is less overall juice there is more grape matter from which to extract and thus essentially increase the concentration of everything taken from the skins. It is more commonly done in years where there is less natural concentration found in the grapes but some producers do it as a matter of course to make a more intense red wine. A little bit of saignée can be done with still elegant results. If a producer removes too much juice the result can be an imbalanced wine. Rosé made from saignée method has gotten a bad rap the last few years but there are numerous examples of well-made saignée rosé. When saignée rosé is made from fruit that is not excessively ripe it can still deliver freshness and just a slightly richer flavour profile than early-picked vin gris. Excessive saignée could easily contribute to a sense of density in the resulting wine and help with the overstuffed effect we are discussing when done alongside other techniques as well.

I am certain there are other winemaking techniques that are behind some of the various wines we are discussing – doing more extraction during fermentation changes things as well but there I tend to experience it as changing the character of the tannin between smoother and more angular, and making the wine go from more finessed with less aggressive extraction to chunkier with more, rather than changing the density of the wine, which is what I have been discussing here.

I hope this helps – again, thank you for reaching out. Let me know if all this makes sense or if you have other questions about it.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,408 featured articles

- 274,574 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,408 featured articles

- 274,574 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes