The sad tale of the disappearing salmon

Nick highlights a particularly wide-ranging new book about one important fish.

For the past couple of months, in addition to humping the many cases of wine addressed to HRH up to our 14th-floor apartment, I have also been humping cases of books.

These are the food and drink books that have come out over the past year whose publishers have entered them for the André Simon Food and Drink Book Awards, of which I am chairman. This is a role I am proud to hold, having begun initially as a food assessor almost 30 years ago, before graduating to become a trustee and then assuming the mantle of chairman about six years ago.

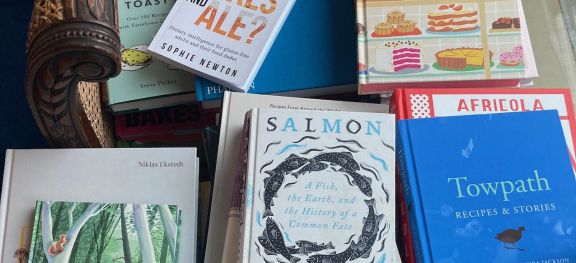

These are just some of the books that have been submitted. They are extremely wide ranging and eclectic, from the Peaky Blinders Cocktail Book to Wine and The White House: A History (which Tam plans to review) to Victoria James’s confession of her experiences as a sommelier in Wine Girl (reviewed by Tam here) among this year’s drinks books. The far more numerous food books, over 120 at the last count, range from Jenn Louis’s paean to the benefits of chicken soup in The Chicken Soup Manifesto, to numerous (far too many?) books on vegan cooking, to Merlin Sheldrake’s book on fungi Entangled Life, to Jp McMahon’s The Irish Cook Book.

As well as myself as chairman, there are three trustees (Xanthe Clay, Sarah Jane Evans MW and David Gleave MW) plus an annually chosen assessor for each of the food and drink awards who are this year Lisa Markwell, food editor of The Sunday Times, and John Hoskins MW. Next week we all meet via Zoom to try and whittle this enormous list of potential winners down to a shortlist of about six food books and four drink books. The winners announced in a virtual ceremony towards the end of January will each receive £2,000.

One of the greatest attractions of being associated with a book award such as this is the constant reacquaintance with writers who have become favourite authors over the years. These writers range from Bee Wilson to Harold McGee, who has this year written another blockbuster, Nose Dive; to Yotam Ottolenghi, who has produced Flavour this year while his business partner Sami Tamimi has co-written Falastin. And then there is Mark Kurlansky.

I have long been an admirer of Kurlansky and everything that he writes, from his first book Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World to Salt to his Basque History of the World, Kurlansky is a writer who recognises how important certain foods have been to human development but also quite how much damage mankind has inflicted on the earth and these foodstuffs as it has exploited the world’s many natural resources.

His most recent book, Salmon: A Fish, the Earth, and the History of a Common Fate (£18.99/$30 Oneworld), explores these two themes in particular: mankind’s destruction of the environment that allowed the salmon to flourish so widely before we polluted the rivers, and how, perhaps very belatedly, we have finally recognised our many mistakes about the damage we have done to the environment. Kurlansky writes about these issues, and more, with the same distinction that he brought to Salt and Cod. But I think he omits one very important aspect of this exceptional fish: its importance to restaurant menus and how chefs would cope with a world without salmon. The scattering of recipes throughout the book is not sufficient recompense.

Kurlansky opens, as every red-blooded American would presumably like him to, with an account of a couple of trips he made on salmon boats in Alaska, the first with Curtis Olsen and his crew and the second with Thea Thomas, an obviously brave woman, who insists on going fishing on her 32 ft (10 m) boat on her own. Both are out to catch sockeye salmon. This is Kurlansky’s method of introducing us to what is salmon’s most distinctive characteristic: that having negotiated their way downriver and out into the open sea where they fatten up, an attribute that makes them able to survive in both freshwater and seawater, they return to their rivers of origin to die. Here, these boats wait to catch them.

Kurlansky spends some time listing what man has put in the way of the salmon as it runs both downriver and upriver. These began with the Industrial Revolution in England and by 1875 were extensive. Kurlansky quotes the Victorian Archibald Young’s list of a small sampling of a few famous British rivers:

‘Dart: chemicals, mines, paper works, wool washings

Dee: oil and alkali works, petroleum, paper works, wool washings

Kent: manufacturers

Severn: sewage, mines, tanneries and dye works

Teifi: debris from slate quarries and mines

Trent: sewage, factories

Tyne: chemicals, mines, coal washings.’

On top of this, organic pollution destroyed the oxygen in the water so that neither fish in the water nor plants on the banks could live. The insects died and so did the fish – trout and salmon – that had hitherto survived thanks to them. One of the issues that this book puts forward most strongly is the interconnections that nature depends on. Break these and the consequences can not only be dire but also long-lasting.

In 1807 salmon were to have a significant role in how the American West was won. It was in that year that Meriweather Lewis, half of the team commissioned by Thomas Jefferson to explore the West, was served salmon by a Native American who told him that they were close to the waters of the Pacific Ocean. They were in fact further than they thought but this was the introduction to the magnificent Columbia River.

But white Americans and Native Americans were interested in different worlds. The former saw commodities: forests for timber; animals for their fur; land for agriculture; fish that could be salted and packed in cans; and, most damagingly for any fish that had to swim down- and then upriver, came the discovery of gold in California. Mining destroyed the salmon runs as the rivers became silted and no longer had the gravel bed that salmon require for spawning. There was less shade as the riverbanks were cleared and within five years of gold being discovered in the Sierras, the Sacramento river no longer had a healthy spring salmon run.

Kurlansky lists the vast number of dams that were built in the 19th and 20th centuries to open up the West. Idaho was apparently one of the most-affected states. Kurlansky shares a recipe for sake-smoked sockeye salmon from Tom Douglas, the well-known chef from Seattle, before adding that today Washington is no longer the salmon producer it once was so that, as in New York, fish has to be flown in from Alaska.

He also explains how salmon were initially a northern-hemisphere fish but that today they have spread – to Australia and New Zealand via the British and their penchant for fly fishing – and to Chile via the spread of salmon farming, a business dominated by the Norwegians. Chilean-raised salmon are now extremely popular in Japan, whose own varieties are Pacific chum salmon, because of the native appetite for salmon eggs, pinks and masu.

Kurlansky ends the book in the Far East, in the remote Kamchatka Peninsula, which, together with Alaska, is now home to two-thirds of the world’s salmon. This peninsula is home to 1,852 rivers and tributaries, where you are more likely to encounter one of its 7,500 brown bears than a fellow human. This region also has the greatest variety of salmon, the six species found in Alaska plus the masu that came originally from Hokkaido in Japan.

But what the so-far-unspoilt wildernesses of Alaska and Kamchatka also share are oil, gas and mineral wealth that could attract the greedy, just as the California gold rush of the 19th century once did, with terrible consequences for the salmon rivers of California. And whether the salmon can survive this onslaught is anybody’s guess.

Kurlansky ends with a sobering thought. He writes on the final page, ‘If our goal is to restore many rivers’ cleanliness back to the disastrous levels of 1950, or even 1850, the salmon will not be restored. The problem is that no one remembers the abundance of salmon before the industrial revolution and so they cannot aspire to it’.

This is a sad but inescapable truth, one which Kurlansky does not shirk from telling in this hugely admirable book.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,422 featured articles

- 274,421 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,422 featured articles

- 274,421 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes