Struck-match wines – reductio ad absurdum?

This is a longer version of an article also published by the Financial Times. Find 1,000 tasting notes on 2013 white burgundies via this guide.

It is not an exaggeration to say that there has been a revolution in white winemaking, and it may well have gone too far. You may not have noticed it as the changes have been made gradually over a few vintages, but the most dramatic examples are white burgundies and their counterparts, the most ambitious Chardonnays made elsewhere.

‘Buttery’, ‘rich’ and even ‘toasty’ used to be terms of approbation for these sort of wines, but no longer. An increasing proportion of them nowadays are notably high in acidity, have no trace of the toastiness of obvious oak, are almost lean on the palate and, crucially, have the tell-tale flinty smell of recently struck matches. These sulphide notes are associated with so-called reductive winemaking in which wines are protected from oxygen during ageing.

One reason for this significant fashion in winemaking (it is a man-made not a natural phenomenon) is as a reaction to what The Wine Society’s experienced burgundy buyer Toby Morrhall calls ‘the pox’. This was the mysterious premature oxidation that afflicted far too many late-20th- and early-21st-century white burgundies and turned them into something not unlike flat sherry. In Burgundy, wine producers horrified by this phenomenon turned sharply in the other direction, reduction being effectively the opposite of oxidation. As Jean-Marc Roulot, one of the most admired producers of Meursault, puts it, ‘there has definitely been a change in the way that producers, and consumers, view reduction, which, thanks to premature oxidation, is now seen as something more positive. There are also some widely admired producers of white burgundy who have opted for marked reduction so that reduction has come to be perceived by consumers as a sign of quality.’ Nose a line-up of white burgundies nowadays, and it can be a fumy experience.

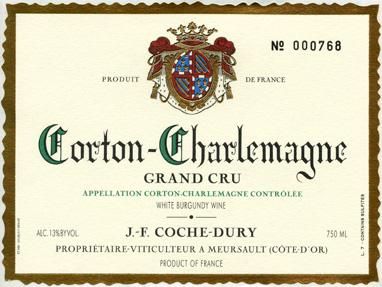

But it is not just a Burgundian fad. It has spread to the country that made its considerable international wine reputation on the basis of its oaky Chardonnays. Master of Wine and Chardonnay producer Michael Hill Smith of Shaw & Smith recalls how a reductive character used to be viewed as a technical fault by judges such as him in Australia’s all-important wine shows. As such it was actively discouraged as potentially ‘masking the purity of fruit expression which was so all-important in our whites in the past’. He notes, however, that ‘over the last three to five years or longer we have seen winemakers of high-end Chardonnay actively seeking to emulate the reductive “struck match” characters found in so many Burgundian whites including Domaines Leflaive and Coche Dury.’

Youngest-ever chair of Australia’s national wine show, the Burgundian-trained producer of Yabby Lake’s admired wines Tom Carson, puts the start of the trend even earlier. ‘I would say it was the early 2000s when it started to become more prevalent, but really it was around 2005 that it was quite noticeable. It has certainly been instrumental in bringing the general wine drinker back to Chardonnay in a big way. These cooler-grown, wild ferment, struck match, flinty and fine wines got wine writers writing about them. They were winning wine shows and the somm[elier]s got on board as well.’ Hill Smith notes that the trend has spread to other barrel-fermented Australian whites, not just Chardonnays.

So how do wine producers go about imbuing their whites with this distinctive character? It is only very rarely shaped by what goes on in the vineyard. Exceptionally in 2004 Burgundy’s vines were sprayed far more often than usual because of the threat of mildew and this encouraged reduction in the young wines, but usually it is the decisions a winemaker makes in the cellar that make the difference. To maximise the struck-match character, which some Burgundians call le matchstick, a winemaker minimises the amount of new-oak influence, eschews the once-fashionable technique of stirring the lees in barrels as this encourages exposure to oxygen, for the same reason minimises the movement of wine from one barrel to another, or at least does it in the absence of oxygen, and might well, like Domaine Leflaive and Roulot, complete the ageing of the wine in tank rather than in barrel. Because there can be considerable variation between barrels as to how much struck-match character each has, some winemakers deliberately top up the space left by evaporation at the top of barrels with the contents of a particularly reductive one.

In Australia other distinctive winemaking choices include ensuring ambient and not cultured yeasts are employed and suppressing the acid-reducing process known as malolactic fermentation. And wherever they are, those seeking reductive wines tend to add a bit more sulphur dioxide prior to bottling than was recently customary. Sulphur, which smells acrid in excess, a bit like the solid fuel coke, was once over-used and led to a swing in the opposite direction, which may well have exacerbated the premature-oxidation problem. But nowadays, as Toby Morrhall comments, ‘having lived through a huge loss in replacing poxed bottles, I am very reassured by a whiff of the sulphur which was prevalent 20 years ago when I first started in the trade. In fact the over-use of sulphur then partly explained the longevity of some wines. One had to wait four years for them to shake off the sulphur. One may have to do so again, but that is better than the whiff of oxidation!’

I’m all for wines tasting fresh rather than flat, but wines in which the reductive character completely obliterates the natural fruit can be both wearying and boring to taste – and if overdone, it can lead to bitterness. It is not enough for a wine simply to smell of struck matches; there has to be something interesting underneath. I sense the creak of a pendulum beginning to swing in the opposite direction. The wines of Coche-Dury and Domaine Leflaive, for instance, two of the most obvious struck-match practitioners, seem to be exhibiting it rather less in recent vintages.

And at least one high-profile white burgundy producer, Dominique Lafon of Domaine Comtes Lafon, is actively against le matchstick wines. ‘Why should I start making reductive wines just to avoid the premox problem?’ he asks rhetorically. Like a handful of quality-conscious producers, he takes pains to measure the dissolved oxygen in his wines, which helps calculate how much sulphur dioxide to use pre-bottling and, using a special new technique, he can even calculate the oxidation risk in bottled wines without pulling the cork.

I for one am looking forward to seeing just a little more fruit and little less matchstick in my white wines.

SOME FAVOURITES

The following burgundy producers could be said to have led the initial charge towards reductive winemaking:

Coche-Dury

Domaine Leflaive

These burgundy producers, listed alphabetically, have been some of their more successful emulators:

Boisson Vadot

Pierre-Yves Colin-Morey

Darviot Perrin

Arnaud Ente

Jean-Philippe Fichet

Hubert Lamy

Pierre Morey

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,430 featured articles

- 274,223 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,430 featured articles

- 274,223 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes