The real balsamic vinegar

Sometimes known as black gold, Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena may not bankroll giant conglomerates or start international wars, but it has a price tag worthy of its epithet. And a bit like crude oil, once it’s a part of your life, it’s difficult to live without it.

I confess to a certain level of blissful ignorance when I set off to Emilia-Romagna earlier this year (blissful refers to the state of my wallet, which has suffered in consequence). I knew that there was good-quality balsamic vinegar, and inferior balsamic vinegar, and was satisfied that because I paid a whopping £9 for my 100 ml at the supermarket, I was buying the good stuff.

The first moment of revelation came when reading the price list at an acetaia (the vinegar version of a winery) where the cheapest balsamic vinegar clocked in at €50 per 100 ml, and the special ones at over €100 per 100 ml. The second came over lunch, watching the unsmiling snowy-haired 80-year-old Italo Pedroni (qualified Master Taster and producer of Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale) drizzling, with slow tenderness, droplets of thick dark syrup from a tiny bottle onto a mound of silky tortellini. ‘Non sull'insalata!’, he admonished, peering balefully over his black-rimmed spectacles at me. As if I’d dare to squander this nectar on lettuce leaves… (I had only ever put balsamic vinegar on lettuce leaves.)

Pedroni’s wife, the long-suffering Franca Prampolini, is the extraordinary cook at the Osteria of Rubbiara. Here we sat at a long trestle table in a room worn by 200 years of hungry customers and watched as bottles of Lambrusco and plates piled high with rich-smelling food were plonked unceremoniously in front of us. No menu. No choices. No margin for picky eaters. No salad. (Definitely no salad!) Men get served first. ‘If you don’t empty the plates, we don’t serve the next course.’ Cowed, I ate enough tortellini to fuel a marathon. It was the first time I’d tasted proper traditional balsamic vinegar, its deep-timbred savoury sweetness adding a new dimension to smoky meat, and the extraordinary burst of sharp flavour when drizzled on home-made vanilla ice cream.

The brown sticky vinegar – aceto balsamico condimento – that we routinely buy in supermarkets tends to be an IGP product and is, to a greater or lesser degree, inferior. It’s made from a blend of vinegar, concentrated grape must and caramels, and because the ageing process is usually only around three months, other ingredients are added to give it flavour, texture and colour. Relatively unregulated, its quality varies wildly.

The proper DOP stuff comes with a grand mouthful of a name: Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena, which can be extended to the grander heights of Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena Extra Vecchia DOP for the aged product. (There is also Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Reggio Emilia, from a wider geographical area.) The rules are strict. It can be produced only in the province of Modena – from the vines to ageing to bottling. It must be made from grape varieties traditionally grown for wine in Modena, most commonly Trebbiano di Modena, Trebbiano di Spagna (Trebbiano Giallo) and any of the Lambrusco varieties, although other varieties grown in Modena may be used. Pedroni, unusually, uses only grapes grown in their own vineyards, and then only two varieties, Lambrusco di Sorbara and Trebbiano di Spagna. There are maximum-yield regulations and the grapes must be picked fully ripe at about 15 °Baumé.

The grapes are pressed immediately and the clear grape juice poured into the large open-top cookers. The must is then cooked slowly for anything from 12 to 40 hours to concentrate the sugars and reduce the liquid (now a thick, sweet coffee-coloured liquid called mosto cotto) to roughly half the volume. High temperatures (over 100 °C/212 ºF) mean fast cooking, which allows for a quick turn-around at harvest, but lower temperatures (80-96 °C) preserve delicate flavours and phenolics. The mosto is left for a couple of months in tank to allow it to settle and clarify.

Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena has a long history, with the first written documents referring to a special vinegar of ‘mature musts’ being aged in 36 barrels in a tower belonging to the Duke of Modena in 1508. In 1747 we see the words aceto balsamico being mentioned, and the production process since then has remained almost unchanged, passed on from generation to generation. It’s in the rarefied sanctum of the acetaia, high up in the loft, dimly lit, the warm air thickly sweet and sharp, stooping beneath old rafters blackened with angels' share, that one feels the skin-prickle of traditions steeped in time.

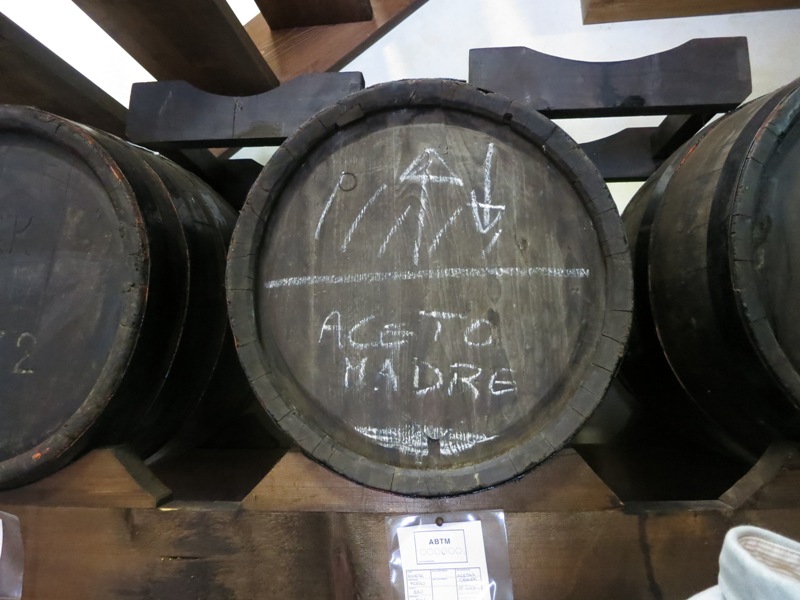

The barrels, tarry black and some warped with age, lie in neat little rows on wooden racks, embroidered squares of fabric over the bung holes, like tiny altar cloths.

The battery, or batteria as it is called, is a 'family' of barrels lined up in a single row, which must be a minimum of three barrels in size, although the older ones sometimes number up to 12. (The longer the batteria, the more complex the vinegar.) On each batteria is inscribed a name – Maria, Rachel, Cesare, Giuseppe; named after a child at its birth, and usually given to that child as a wedding present, the batterie are family heirlooms, handed down with great reverence from generation to generation, cared for more tenderly than precious antiques, and above all, never blended. ‘Batteria? Is like family’, I was told. ‘We do not mix the families!’

The barrels can be made of chestnut, cherry, oak, mulberry or juniper, each wood giving a different character to the vinegar. Cherry gives fruit and sweetness; juniper gives a medicinal spice; chestnut, deep, savoury, coffee-tinged; oak, sweet warm spice and prunes. But the most important aspect for a balsamic-vinegar producer is the bacteria which lives inside the wood. Each acetaia has its own unique – much treasured and guarded – population, which gives the vinegar its signature flavour profile. The barrels are therefore never emptied or cleaned. The most sacred barrels are the botti madri – the mother barrels – which can be anything from 100 to 200 years old and produce the finest vinegar. When they start to leak too much, the barrel is simply covered by another layer of wood. Some botti madri can be three or four barrels thick. No retirement age for balsamic vinegar barrels!

Making genuine balsamic vinegar is a pursuit of patience, a game of quiet waiting. The most ‘basic’ product must be aged for a minimum of 12 years. The more sought-after vinegars age for 25 years to over 60 and are called Extravecchio. I stuck my nose into a little 150-year-old barrel, the vinegar glistening, still and viscous as liquid tar and breathed deeply: fig, just-brewed Turkish coffee, walnuts, anise. Each year, about 10% is lost to evaporation – about 50-100 cl from each of the smallest barrels (worth around €800). Each year, they draw off about 10% (never more than half the barrel) for bottling – just a litre, sometimes less, from each batteria. Each litre bottled represents 1,000 litres of grape juice.

Once they have drawn vinegar off the smallest barrel, two litres from the next barrel up is used to replace the one litre bottled and the one litre evaporated. The process is repeated all the way up until they reach the largest barrel, which is topped up with the new vintage cotto most, solera-like.

After removing the vinegar, it goes to the Consorzio to be tasted, approved and certified. The Consorzio alone is authorised to bottle Aceto Balsamico di Modena Tradizionale. It goes into a regulated 100 ml black glass bottle – a bit like an upside-down light bulb with a square stand on the bottom, and the Consorzio applies the back label, the cork, the capsule, a seal of approval, and a number. The producer is, at least, allowed to apply the front label.

Before we tiptoed out of the silent womb-like warmth of the acetaia, where the vinegars were ‘only just waking up after their winter sleep’, we were allowed to taste a spoonful of an 80-year-old vinegar. I felt like a child taking communion as I took the tiny spoon of syrup and put it in my mouth: treacle, fig preserve, raisins, and a dark Bovril-like flavour, then, lingering, the taste of Manuka and a shot of mouthwatering acidity, leaving the taste of apricots and salt.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,401 featured articles

- 274,903 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,401 featured articles

- 274,903 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes