Sixty vintages under his belt

This is a longer version of an article also published in the Financial Times.

This article was first published on 31 March 2007. We are re-publishing it today in our Throwback Thursday series to complement today's review of recent vintages of Ch Figeac, including the first of the new, post-Thierry Manoncourt era.

See also Sixty vintages of Ch Figeac, published in 2007.

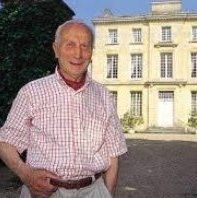

In January 1947 Thierry Manoncourt, a 29-year-old Parisian, arrived to inspect a property his mother's family had acquired, somewhat reluctantly, in 1892 in the south of France, having agreed to spend a year there. He has now made 60 consecutive vintages of Château Figeac in St-Emilion. I may have overlooked someone but I cannot think of anyone anywhere in the world who has been in charge of a wine estate for this length of time, much less someone who celebrates his 90th birthday in September and yet looks so extraordinarily youthful.

I saw him receive a lifetime achievement award in Germany earlier this month. He and his even more youthful-looking wife Marie-France had recently returned from a major wine junket in Singapore and Bali but they still went to bed long after me. Their smooth visages arguably do even more for the reputation of the therapeutic properties of wine than the grape-based spas and cosmetics currently sprouting around the world.

It truly was by accident that he became a vigneron. A great, great grandfather built the Moscow-St Petersburg railway line for Tsar Nicholas II. His father made the weighing scales used by Marie Curie in her researches into radioactivity. He himself trained as an agronomist in Paris where he expected to work and where the family had long been based, never having had any intention of visiting their neglected Bordeaux château. The only reason for leaving Paris was to escape the heat, so the south west held none of the attractions of Brittany and the alps.

But it was Manonourt's training at the Institut National Agronomique that sowed the seeds for a lifetime's work on this, one of the oldest and most respected estates on Bordeaux's 'right bank' (St-Emilion and Pomerol most notably). He brought to Figeac such an enquiring, scientific mind that he could not bring himself to leave it. This in an era when most comparable properties were being run by hired hands, typically men whose chief influences were the practices of their fathers and grandfathers before them rather than any formal training.

Manoncourt saw immediately that there was a great deal to be done. He set to work sowing cover crops in the vineyard to improve the health of the soil and was one of the first to abandon the copper sulphate treatment known as 'Bordeaux mixture' for the same reason. In the cellar one of the first jobs he had to tackle was bottling the legendary post-war vintage 1945. He noticed that the quality of the wine varied considerably from barrel to barrel, particularly although not exclusively according to the age of the oak. He accordingly set the lesser lots on one side and bottled them together as a second wine, La Grange Neuve de Figeac. This 'second wine' still exists today, was used for the entire miserable 1951 crop, and preceded all but a handful of second wines from Bordeaux's top echelon, the first growths.

He also became so interested in the different grape varieties planted in the vineyards, accepted as a fait accompli by most growers then, that he made trial vinifications of each variety separately and studied the resulting wines over time – a completely unknown practice in Bordeaux and the rest of France in the pre-varietal era. This led him to realise that Cabernet Sauvignon, to this day unusual on the right bank, made far better wine than Malbec and resulted in a significant replanting of the estate. Today Figeac is famous for its high proportion, more than a third, of Cabernet Sauvignon, traditionally associated with the left not the right bank.

In 1970 he was one of only three producers in Bordeaux to undertake the expensive but now widespread practice of putting the entire harvest into brand new oak barrels because the vintage produced wine that was concentrated enough to withstand it. He was also the first owner of a right bank estate to install stainless steel fermentation tanks in place of the traditional wooden ones, in 1971, preceded only by first growths Châteaux Latour and Haut-Brion.

Figeac's official status has long been a source of irritation and disappointment to Manoncourt. It is never long before visitors to the handsome, prettily decorated château in which the Manoncourts have lived for so long are told how, to make ends meet, past owners of Château Figeac, once the pre-eminent estate of the right bank, sold off successive slices of the original extensive property, including one particularly desirable section of gravel which was to become Figeac's famous neighbour Château Cheval Blanc (whose wine was originally sold as a 'vin de Figeac'). When the châteaux of St-Emilion were first officially classified in the early 1950s, Cheval Blanc was ranked one very important notch above Figeac. Every time this classification has been revised since – five times and most recently last year – Manoncourt has lobbied hard but in vain to have Figeac elevated to 'A' status alongside Cheval Blanc and Ausone.

Few proprietors have single handedly been responsible for more 20th century innovations than Manoncourt. His agronomist's training helped him find an effective treatment against rot which saved his grapes in the disastrous 1968 vintage and meant that Figeac was the only St-Emilion to be granted premier grand cru classé status in that miserable year.

He also claims that, thanks to this scientific training, he was able to master the important second, softening malolactic fermentation right from his very first vintage in 1947 and that Professors Peynaud and Ribéreau-Gayon, often credited with controlling it, used to visit him to try to work out why he was not plagued by the problems of le malo that everyone else experienced at that time. In the early 1970s he also created, with the help of his architect friend Jacques Lhuillier who had designed Paris's Maison de la Radio in the 1960s, a particularly smart underground cellar with glass doors – so innovative at the time (de rigueur nowadays) that California's Robert Mondavi came to view it no fewer than seven times.

I suspect the Californian might also have been encouraged to return by the quality of wine served at Figeac. Being free of the exigencies of a board of shareholders, and having many decades of his own wines to choose from, Thierry Manoncourt has tended to pull out some magnificently mature vintages at his dining table. Figeac, having been made by the same man for longer than any other bordeaux, has a particularly distinctive, traditional, one might even say rather unfashionable style. Unlike most other wines shown en primeur every spring, it gives no indication of having been groomed to charm tasters at this early stage and is easy to under-estimate in its first few years, perhaps partly because of the Cabernet Sauvignon too. But from about 10 years on it can be, and frequently though not invariably is, quite majestic. This must imbue a certain confidence in the chef-patron, now assisted by his son-in-law Comte Eric d'Aramon.

Like one of the very few other Bordeaux wine notables who actually lives full time at his château, Anthony Barton of Châteaux Léoville- and Langoa-Barton in St-Julien, Thierry Manoncourt has known family tragedy. Both lost their only sons in accidents close to home. Both were garlanded with major awards this month: Barton was made Decanter magazine's Man of the Year; Manoncourt was given this year's Lifetime Achievement Award by Weingourmet magazine in Germany.

Co-founder of the influential Union des Grands Crus de Bordeaux which did much to press Bordeaux's highly effective suit in Asia, beginning in Japan in the wake of the oil crisis in the early 1970s, Manoncourt is still very much part of the acceptable face of Bordeaux.

Apr 23 – I have just received the following message from Alessandro Soldi of Florence:

'I read with great pleasure the story about Thierry Manoncourt and his 60 consecutive vintages of Chateau Figeac. At Easter time I was in Langon in the nice hotel restaurant of Claude Darroze and I was drinking a Doisy Daene 1949 (incredibly lively for that age) when a nice man introduced himself as Pierre Dubourdieu, 84 years old, the maker of that excellent vintage. He suggested to drink a glass every day to live 100 years. Unfortunately the barrier of the language stopped the conversation but the intensity of it was outstanding.

'I hope to see again Mr Dubourdieu next year and it is not very unusual to find a French vigneron with 60 vintages in the palmares, especially if you drink a glass of Doisy Daene every day.'

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,396 featured articles

- 274,621 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,396 featured articles

- 274,621 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes