The vine moves Polewards

Yet more evidence of the expansion of the wine world. A shorter version of this article is published by the Financial Times. Above, the Adoria vineyard in winter. See also A Polish wine invasion. At the bottom of this article is a new feature, an addition to Jancis's FT articles designed to address some of the more fundamental aspects of wine.

Vodka is losing ground to wine in Poland. And it’s not just because summers have, as in so much of northern Europe, become warm enough to ripen grapes reliably.

It’s more a symbol of the westernisation of Poland, a sign that Poles travel widely, once to work and now, much more commonly, from their prosperous homeland to take holidays in warmer countries where wine is part of everyday life.

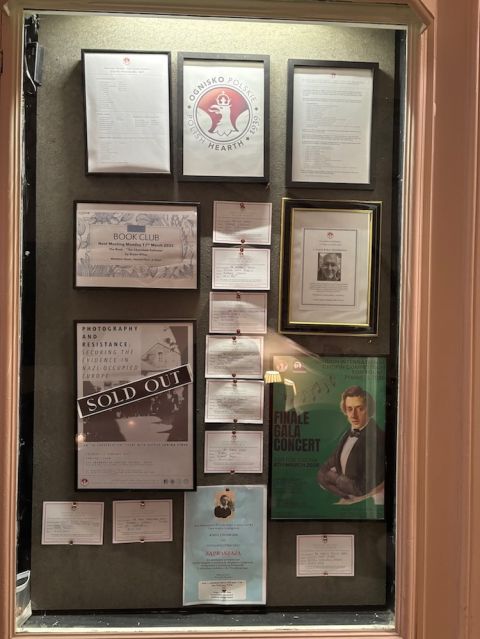

At a recent Taste of Poland event at what was the Polish officers' club in the Second World War when General Sikorski and the rest of the Polish government were exiled in London, 19 wine producers took part and just seven spirits distillers – as well as one producer each of beer, goat's cheese, preserves, and a particularly popular table doling out ‘real caviar’.

But the wine producers there represented a tiny fraction of the country’s total. According to Poland’s only Master of Wine Wojciech Bońkowski, more than 500 wineries (winnica in Polish) are officially registered, with around 200 of them sufficiently well established to sell more widely than at the cellar door. (Since the publication of this article I was informed by Katazyna Odunuga who represents Wine of Poland that more than 700 have now been registered.)

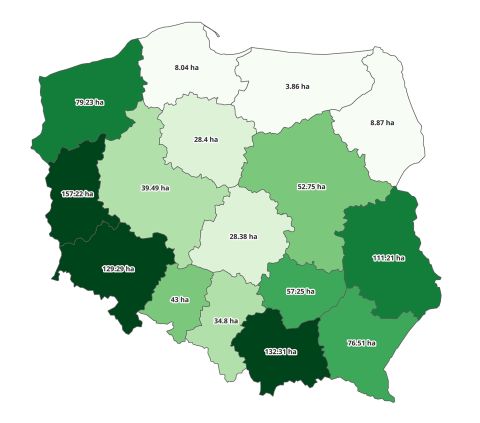

The wonderfully informative website EnoPortal.pl maps the location of each winery and, rather than clustering in one relatively warm zone, they’re all over the west and south of the country with the heaviest concentration towards the border with Slovakia. But one of the two biggest, Turnau founded by a successful farming family, is located in the far north-west, its growing season extended by the moderating marine influence of the Baltic. There are even a few wineries in Poland’s most continental corner in the far north-east, but no appellation system as yet.

The website even maps the distribution of individual grape varieties, which are generally highly distinctive. Although about 15% of vines are as familiar as Riesling, Chardonnay and the Pinots, much more common are hybrids, called PiWis in Germany, such as Solaris, Souvignier Gris, Hibernal, Johanniter, Muscaris and Seyval Blanc for white wines, and Rondo, Regent and Cabernet Cortis for reds. All of these have been specially and sensibly bred to resist disease so as to obviate the need for agrochemicals and/or to ripen early enough to escape the onset of the Polish winter. The young couple presenting the ambitious wines of Marcinowice winery disagreed as to whether Riesling or Pinot Blanc is the best variety for their bit of western Poland.

The Bacchus vine is also fairly popular, just as it is in England. In fact I was struck by several similarities between the wine industries of Poland and the UK. Despite both countries having a history of grape-growing in the distant past, in the modern age this is a recent phenomenon, in England from the second half of the last century and in Poland only really this century. Among the 50-plus Polish wines I tasted at the recent showing, it was the handful of traditional-method sparkling wines that stood out, as in the UK – although, as in England now, there were some impressive still wines.

There was no qualitative difference between wines made from hybrid grapes and the rest. From both Majątek Drzewce and Turnau (whose vineyard is seen below), for instance, I preferred their Solaris to their Riesling at the tasting. Whites were generally more successful than reds but as summers warm up and vine age increases, I would expect the quality of Polish Pinot Noir only to improve.

Poland is clearly no vinous backwater. Jazzy labels, orange wines and lightly sparkling pet-nats abound and some creativity had been put into some of the wine names. A pink pet-nat made from Cabernet Cortis and Regent and stoppered by a cork tied on with string, was called Rosecco. Silesian winery’s pet-nat based on a blend of PiWi varieties was called Piesecco, while their Rondo was labelled Rondo-Vous. Witaj Słońce makes wines, both red and white, called simply and rather appealingly Euphoria.

English wine also came immediately to mind when the UK’s only Polish wine importer Adam Michocki began to explain the economics of producing wine in Poland. According to him, Polish wine is relatively expensive because most of the producers are small, newish, family-run enterprises that make wine as well as growing grapes. Unlike in Poland, in England some vineyard owners simply sell grapes so they don’t have to invest in winemaking equipment, but the cost of hardware is a major headache for Polish winemakers, most of whom have had to borrow heavily and are all first-generation. ‘I say making wine in Poland is like making wine on the moon’, says Michocki, referring to the lack of facilities, although a few producers are starting to form associations within which equipment can be shared.

He was born and raised in Poland and came to England in 2016 as a sommelier, specifically to take wine exams (he is now studying to be a Master Sommelier). He worked in some smart, wine-minded restaurants, including Chez Bruce and The Glasshouse, and apparently found customers generally receptive, with a little nudging from him, to the cool, pure flavours of Czech wines. ‘When I served them, people had some joy and sparkle in their eyes’, he claims now.

This, and the wine boom taking place back home, emboldened him to switch to importing and he started Central Wines specialising in Polish wines in September 2021 – during lockdown when wine-drinking was enjoying a worldwide boom. He does sell wine online but his chief focus is selling to Michelin-starred restaurants. He proudly volunteered that his wines are in two three-star establishments, six two-star ones and 19 one-star restaurants.

His sales pitch to them is that Poland’s dry Rieslings can compete with and undercut Germany’s Grosse Gewäche wines, and the Chardonnays can do the same for the lesser wines of Burgundy. ‘And there are also lots of people looking for unusual grapes and the exotic flavours of the hybrids – they’re the grapes of the future’, according to Michocki.

I enjoyed all the wines listed here. Most of them were dry even though the domestic market was largely weaned on to wine via medium-dry styles. But the wine I really savoured, Adoria Riesling 2021, was enjoyed when I returned to the place where the tasting had taken place for a Sunday lunch in the (quintessentially) Polish restaurant Ognisko on the ground floor. It was the one and only bottle of Polish wine run to earth by the staff during a busy lunch full of Polish families. I was told by Michocki that the six or seven Polish wines they tried out there didn’t find favour with the substantially Polish clientele, perhaps because the list as a whole is excellent, wide-ranging and very fairly priced.

The tasting event on the floor above the restaurant had been so crowded that I got the impression that every Pole in London was there, and they all seemed very interested in the wines. This being the first-ever generic Polish tasting in the UK, the ambassador was there to make a speech and provide encouragement.

This house in South Kensington really is the heart of Polish culture in London. In the entrance hall is a black and white photograph captioned ‘General Władysław Sikorski, Helena Sokorska and Lord Halifax at the official inauguration of Ognisko Polskie (Polish Hearth) 16 July 1940’. On the notice board next to it is a list of this year’s 16-strong Executive Committee followed by the seven members of the Appeals Panel. My appeal is that they revisit Polish wine.

Superior Polish wines

The Poles are so keen on wine that very little Polish wine leaves the country – hence the lack of stockists this week.

Sparkling wine

Adoria, Metodą Tradycyjną Brut Nature 2022 12.5%

Turnau, Classique Brut NV 11%

£44.90 Central Wines

Still whites

Adoria Riesling 2021 13%

Dom Charbielin, C Souvignier Gris 2023 12%

Dwór Wilkowice Bianca 2022 11.5%

Folwark Pszczew Riesling 2022 10%

Turnau Solaris 2023 12.5%

£29.80 Central Wines

Turnau Chardonnay 2023 12.5%

Reds

Marcinowice, Klony Francuskie [French clones] Pinot Noir 2022 12.5%

For tasting notes, scores and suggested drinking dates, see A Polish wine invasion. For international stockists, see Wine-Searcher.com.

| How do grapes ripen? |

|

The grape ripening process transforms the tiny flowers that appear on the vine in early summer into luscious, juicy grapes picked in autumn or, increasingly nowadays, late summer. The flowers need to be pollinated before they turn into hard, bright-green baby grapes that, during summer, will build up sugars and lose the excessively tart acidity that characterises them initially. The sugars build up in grapes, and all sorts of plants, thanks to photosynthesis. Using solar energy, water is drawn from the soil and combined with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere taken in via stomata under the leaves to form sugars in the fruit. A certain minimum amount of sunlight is needed for this to happen (which is why viticulture is impossible too close to the poles), but if it gets too hot, the stomata close and photosynthesis stops. Vines are then said to shut down. Ideal is a slow, steady ripening process. |

| For much more detail, see The Oxford Companion to Wine. |

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,403 featured articles

- 274,903 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,403 featured articles

- 274,903 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes