24 October 2022 Despite economic adversity, Lebanon’s winemakers have shown they can make exciting, innovative wines. The state must build on these gains, argues journalist and wine writer Michael Karam. Above, the snow-capped mountains in the western Bekaa Valley with the vineyards of Kherbet Kanafar in the foreground.

Multiple calamities have befallen Lebanon over the past three years. In no particular order: the local currency lost 90% of its value; the much-vaunted banking system was exposed as the architect of a Ponzi scheme that wiped out billions of dollars in savings and pensions; an already creaking infrastructure all but evaporated; there have been shortages of medicine, fuel and petrol; and then on 4 August 2020, a significant swathe of Beirut was devastated when hundreds of tonnes of badly stored ammonium nitrate at the city’s port exploded, causing one of biggest non-nuclear blasts in history. Oh, and there was also COVID-19.

Understandably, Lebanon’s 11-million-bottle wine industry has been up against it. When the lira began tanking in October 2019, the obvious thing to do was focus on exports, but the pandemic soon put a stop to that. With both hands tied, they had to reach deep into their Phoenician DNA and their reputation for entrepreneurial genius and crisis management.

And necessity really has been the mother of invention. Amid the economic chaos, there have been significant bursts of unparalleled innovation and evolution, an awakening of sorts, one which has seen many winemakers make wines that better reflect their origins and give genuine, regional context.

This new generation of young, less conservative winemakers now talk of skin-fermented whites and amphora-ageing. They make pet-nats that wouldn’t look out of place in Shoreditch or Brooklyn and a traditional-method sparkling wine from vines grown on the banks of Lake Qaraoun at 900 m (2,950 ft) elevation (see above). All this would have been unthinkable 10 years ago, when Lebanon rode on a global reputation for making muscular reds.

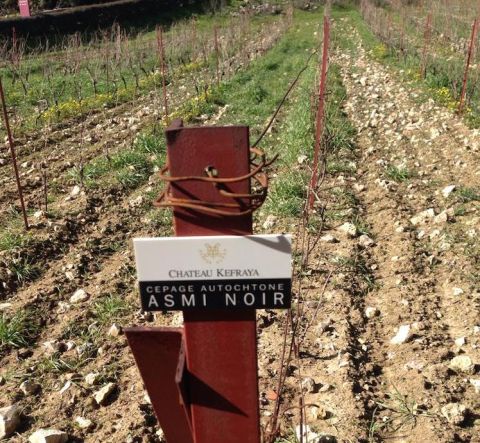

Indigenous varieties such as that shown above, the mere mention of which would have once prompted mass pearl-clutching among the status-conscious Lebanese, are now paraded with pride. Ditto the so-called ‘heritage’ grapes – Cinsault and Carignan in particular but also Grenache – pioneered by the Jesuits in the mid 19th century and which reigned supreme in the Bekaa Valley for 130 years before being pushed aside by the so-called cépages nobles.

Even in the less radical areas of the industry attitudes are shifting. The reds are less butch and the use of oak more thoughtful. Syrah, the grape that once played a secondary role to the mighty Cab and Merlot, now sits alongside the Rhône varieties as Lebanon’s current darlings. Saperavi and the local Aswad Kerash (‘Black Belly’) are also staking a claim for top billing.

And then there are the high-altitude whites, the revelation of the past 15 years. No longer flabby afterthoughts, they are fresher, more diverse, and arguably more elegant and exciting than their red siblings. Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and Viognier led the charge, riding into the Bekaa full of cosmopolitan swagger, showing the world that Lebanon could make achingly beautiful whites as well as barnstorming reds. But now, Merwah, Obeideh, Meksassi and even Assyrtiko, have shown they can also deliver a unique and profound expression of terroir.

But with all this activity there must be more focused regulation. Part of Lebanon’s charm is the laissez-faire way in which the industry operates, but there has to be at least minimal oversight and it is time for the National Wine Institute, envisioned in 2001 but only now getting into its stride, to finally deliver on its mandate and be responsible for all areas of grape growing and wine production.

But there is a higher calling. Pace the weapons-grade cannabis, wine is Lebanon’s most high-profile export, one with many assets at its disposal – the Bekaa Valley, the mountains, the diversity of styles and varieties, its rich francophone culture, and its key role in the history of wine. Throw in Lebanon’s fabled cuisine and you have a devastating combination of culture, civilisation, tradition and conviviality.

Wine is the soft-power tool Lebanon needs, not only to combat its pesky reputation for conflict, chaos and instability – 30 years on Westerners still make kidnap jokes – but also for helping push that most important of messages, that Lebanon is a genuine wine-producing country. It’s simple. Sell Lebanon and you sell the wine.

The trick is doing it properly and here is where the National Wine Institute must learn from the mistakes of the past ten years when the Ministry of Agriculture spent nearly $1 million to market Lebanese wine by hosting lavish, but useless, events in random capitals, the pick of the bunch being the 2013 Lebanese Wine Day at the Georges V in Paris. It was a masterclass in nepotism, waste and incompetence. It spent more in one day than the privately funded Wines of Lebanon generic campaign in the UK spent in an entire year. The latter won IWC Generic Campaign of the Year and saw sales increase by over 30%; the former left town with nothing but a big bill.

Marketing wine is not like marketing chickpeas, and if Lebanese wine really wants to kill off its image as an ethnic curiosity, best paired with kofta and humus, it needs professionals with years of experience in the global wine market to help them do it. So the institute must agitate for a strategic campaign to harness and promote all that is good about Lebanon through the lens of wine and everything else that goes with it.

Get it right, and the industry and, more importantly, the country will thrive. God knows, they both need it.

Michael Karam's book Lebanese Wine: A Complete Guide to its History and Winemakers will be published in 2023.

Main image credit: Château Ksara; all other images are the author's own.