I have known Ferran Adrià, the exceptional Catalan chef, ever since 1996 when I first ate at El Bulli (or elBulli as it has been styled since 2000), the restaurant on the coast outside Roses, north-east Spain, which he made so famous.

Since then we have become quite close friends. I ate for the last time at elBulli shortly before it closed permanently in 2011, and we worked together at Somerset House in London when Adrià brought the first of his touring exhibitions, The Art of Food, to the city in 2013. I even cooked for Adrià once in our house, roast grouse with all the trimmings!

Despite our friendship, and the fact that every meeting and farewell opens with a series of hugs, communication with Adrià has never been easy.

He speaks Catalan and Spanish, which I do not. He speaks only a few words of English. We both speak French but Adrià’s French is rapid-fire and soon slips into Catalan, so that I have always had trouble understanding him. The presence as a translator of Ferran Centelles, who began his career working as a young sommelier at El Bulli in 1998 aged 17, at our most recent encounter in Barcelona was invaluable.

Over the years, Adrià appears to have hardly changed physically. He still has the same quantity of hair, although it is now a bit greyer than before. He still wears the same relaxed clothes. When we last met in July 2019 he was wearing a black and red T-shirt from OSSO, a sustainable butchery and restaurant in Lima, Peru, and a pair of jeans.

He still bristles with the same amount of energy. In particular, he has the most intense eyes, which seem to focus almost maniacally on you. Those eyes must have played a vital role during the 25 years he supervised the kitchens at elBulli, where 48 chefs were employed to cook for a maximum of 50 customers in a kitchen famous for the creation of so many new and fascinating dishes. The textured vegetable panache; the two new ways of presenting a ‘chicken curry’; and in 1994, the world’s first foam, incorporating white beans and sea urchins.

For the past eight years, the future for Adrià and the site that was elBulli have posed something of a quandary even to his closest associates. In 2015 his business partner Juli Soler, who had started work at elBulli even before Adrià, passed away. Plans were quite advanced for the conversion of the restaurant site into the elBullifoundation in which young chefs, the next generation, would learn the secrets of what made this restaurant so great.

The project in Cala Montjoi where elBulli is located will be called elBulli1846, and it will be a creativity centre not just for chefs but for other professionals. The works for elBulli1846 are almost finished and the centre is likely to open some time in spring 2020 with the ecologists finally placated. Adrià’s obsession lies with innovation and creativity and he is determined to dedicate the former elBulli site to both.

.

Adrià has never lacked for financial backers, including several described as ‘angels’. These range from Telefonica, the giant Spanish telecoms company, to Caixabank, Grifols (the multinational pharmaceutical company) to Lavazza, the Italian coffee company. Adrià has been able to secure backing for almost anything he wants, thanks to elBulli’s global reclame. It was voted The Best Restaurant in the World on five separate occasions. He even featured as an (instantly recognisable) character on The Simpsons in 2009.

But it is where Adrià has been planning the next stage in the transformation of elBulli that will come as a shock.

For the past four years Adrià has been holed up in a cavernous two-storey office in Barcelona's Parc de Montjuic above what is very obviously to the nostrils a somewhat incongruous Indian restaurant.

We reached his anonymous premises via a narrow and rather shuddery lift. He sits at the far end of what feels like a warehouse of memorabilia. We walk past a number of cases that hold many of the items that will form the bedrock of his eventual museum, and then past a long stretch of magazine covers and newspaper cuttings from his heyday years that hang from the ceiling. There is the front cover of Time magazine, the front page of The New York Times, and, as we approach the man himself, I notice the full, framed front page of the Financial Times, complete with his photo, from the day after he announced elBulli’s closure at Madrid Fusion in January 2010 when he was only 48.

Adrià is sitting opposite a large screen projected on to the far wall. It is of the elBulli site in all its glory. He then moves it on to reveal a screen with the following icons: cooking activities; ‘empowering creative’; ‘linking knowledge’; and finally ‘creativity’.

‘This is what we are doing here, building the future for the next generation of chefs', he avers reverentially. Then, focusing his eyes fully on me, he asks, ‘Tell me, Nick, what is molecular cooking?’ And before I can even begin to stammer out an answer, he replies, ‘You will have to tell me, because I don’t know.’

But here Adrià and his team are building an archive that will leave a permanent record for anyone interested. ‘We have digitised over 150,000 items that include all my recipes from day one. And we will rename the restaurant site 1846. This will take its name from the number of distinctive recipes I created and the fact that that is also the year Auguste Escoffier, the founder of the principles of French cooking, was born.’

Adrià abruptly stands up. It is difficult to imagine him stationary in any position, whether sitting or standing. ‘Come with me', he instructs, rather as though we are junior members of his kitchen brigade.

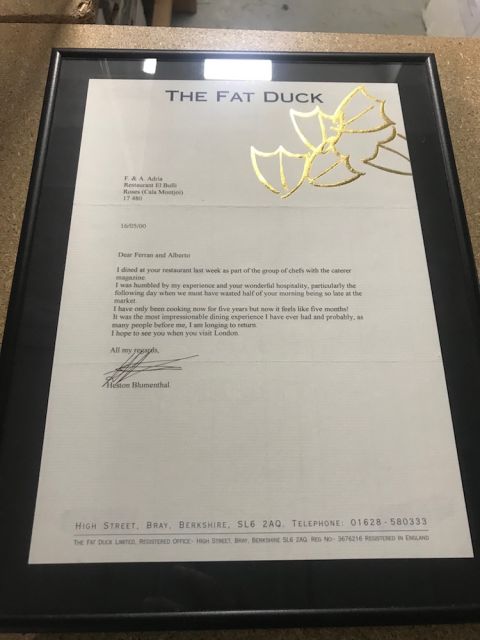

We stop at the first of many glass-topped cupboards. In the first is a photograph of Adrià alongside Alain Ducasse, the great French chef, and the late Paul Bocuse, the chef who made Lyons such a gastronomic attraction. Adrià is justifiably proud of this as he is of the next two exhibits, letters or emails from Heston Blumenthal, chef of The Fat Duck in Bray, Berkshire, and from René Redzepi, who created Noma in Copenhagen, Denmark, thanking and congratulating Adrià, after each had enjoyed their obviously inspirational first meal at elBulli.

‘Come with me', Adrià exhorts, ‘this is what I would like you to see.’ We come to two large walls that run the width of the building. ‘This wall contains the secret of how elBulli made its money. We were in essence a consultancy and mentoring business with a restaurant attached.

We were open only six months of the year because that was the period from May to early October when the customers would willingly reach us. That gave us plenty of time to focus on working with companies who would pay for the association and we could benefit with our skills. And that is what made the restaurant profitable. This was a considered decision. We were a restaurant as intent on being profitable as we were on being adventurous in what we cooked.’

On the wall was a column for each year listing the growing number of companies that willingly aligned themselves to Adrià, Soler and the elBulli brand. There is Lavazza; Barclays; Nestlé; Pepsico; Fast Good, the restaurant concept Adrià created for NH Hotels; and the development of Inedit Beer together with Barcelona’s beer Estrella Damm which brought huge benefits to both sides.

‘These associations made all this possible', Adrià pronounced, throwing his arms wide open to the display cabinets all around us. There were the baroque staff uniforms in heavy material that the owners of elBulli used before Adrià and Soler took it over; papier mâché models of how elBulli was laid out; and the bill for 2.5 million pesetas (£14,000) paid for by Adrià and Soler to cover a unique series of dishes all still preserved in a silver coating. Also displayed were large prototypes of the many bits of kitchen equipment that Adrià adapted such as the Pacojet that today, at just under £6,000, no modern chef will open a kitchen without. Surrounding the cabinets are shelves of books with the heading ‘Creative Cookery Books’.

As we head over to one particular display cabinet, Adrià continues expansively. ‘By 2023 all of this will be housed in a 6,000-square-metre museum at a so far unspecified location in Barcelona. This will be, along with the 35 books which we are publishing, of which eight have already appeared, my culinary legacy.’ This will all come under the title of Bullipedia, a gastronomic encyclopedia that Adrià hopes will become the reference for all future generations. Our Spanish specialist Ferran Centelles, seen at work on Bullipedia below, has already produced three massive tomes on wine.

This display cabinet is different from all the others in that what it contains is far more colourful. They are pink, blue, green, orange and yellow, different shapes and sizes. ‘These', Adrià explains with great pride, ‘are the physical replicas of the many ingredients I created so that the dishes can be brought back to life on the plate'. Below, Adrià marvels at a screen showing all 1,846 of these dishes.

But my initial question remains: why has Adrià, ably assisted by a considerable team which includes Soler’s son Panxo and his daughter Rita, devoted so much time, effort and money into ensuring that his culinary legacy will be preserved? The answer is both personal and historical.

The personal part lies in the fact that there has probably never been a closer association between a style of cooking – molecular (whatever that may be), a place, elBulli, and one chef, Adrià, who made it all possible. This association has been rendered all the stronger, and all the more poignant, by the death of Juli Soler, elBulli’s genial business partner, the strong front-of-house presence who made it all happen.

The historical answers lie in the files and cupboards that fill the floor below, to which we now adjourn. Here Adrià’s team has compiled an enormous reference library devoted to the history of cooking and, in particular, the nouvelle cuisine that revolutionised French cooking in the late 1960s, initiated by chefs such a Roger Vergé, Michel Guérard and Pierre and Jean Troisgros, before sweeping through the rest of the world.

But as Adrià flicks through copies of Gault & Millau, the leading French culinary magazine of the era, he turns to me and says, ‘But where are the visual records of all the wonderful dishes these French chefs created? There is not one. And that must be a huge disappointment for everyone: for the chefs who were so inspirational; for the customers of the time; and for the subsequent generation of chefs.’

Adrià and his team are working hard to ensure that this sad state of affairs will not befall the culinary revolution that they initiated.

The call for the first 'students' is currently available online at https://elbullifoundation.com/elbulli1846/en/.