What's in a number?

In this age of scientific accuracy, we are surrounded by precise numerical measurements that aid our decision-making. The power of a car, the price-earnings ratio of a share, the calorie content of a yoghurt are all simple, measurable facts that can affect whether or not we buy the thing in question. With the wine market being so fragmented, diverse and complex, it is hardly surprising that rating wine quality numerically has become de rigueur. Scores are easily digestible nuggets of information that suggest a greater precision and objectivity than evaluative terms such as ‘good’.

I for one find them useful: as an instant record of my own opinions, as a starting point for group evaluation when judging, and as a convenient shorthand for the assessments of other critics. Scores are, however, one of those familiar concepts that become stranger the more closely you examine them. Here are some observations about scores that can at first seem counter-intuitive.

Scores do not measure anything. Being numbers, scores bear the appearance of measurements; therein lies much of their persuasive power. The natural answer to the question ‘what do scores measure?’ is ‘the quality of the wine’. But quality is not like length, sound pressure or half-life; it carries no unit like metres, decibels or seconds. Nor is it like a football score, arrived at by counting discrete events. Quality is a composite feature of a wine, arising out of attributes such as harmony, intensity and complexity. These individual merits themselves carry no unit either, and moreover their relative contribution to quality is dependent on both the wine and the taster. Since the base attributes cannot be measured, and there is no standardised formula that combines them, wine scores do not measure a property of a wine itself. So what are they?

Scores are medals in disguise. The philosopher Richard Shusterman draws a useful distinction between judgements of quality that describe the object itself, and those classed as performances. Giving medals at wine shows is an example of the latter: there is nothing about a wine that is inherently ‘gold’. Rather, the judges perform an act of praise in awarding such a medal. Similarly, there is nothing inherently ‘17’ or ‘90’ about a wine; these numbers are actually just the names we use in a more elaborate system of ‘medals’. The broad categories of gold, silver and bronze are divided into smaller groups, given numerical names to avoid our having to remember a list of 10 or 50 different metals.

Scores are arbitrary, which is not to say that they are random. But imagine two critics faced with a thousand wines. Now imagine, unlikely as it is, that they agree completely on how the wines should be ranked in quality: their favourite is the same, as is their least favourite, and every other wine in between. Their judgements are thus identical – and yet the scores they give could be very different. Critic A might choose to give the top three wines 19 points, and the next four wines 18.5, while critic B might begin at 18 and then drop to 17.5 after only two wines. By the time we reach the wines of average quality, there may be large disparities in the scores, despite the critics’ complete agreement as to the relative merit of all the wines. Nothing can determine where the boundaries between scores should lie on the quality continuum, or who is correct in this example; it is a matter of whim, beliefs and circumstance.

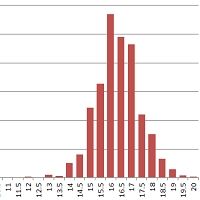

90 does not equal 90. It follows from the above observation that we cannot assume different critics mean the same thing by identical scores. They might choose a different score to represent an ‘average’ wine, and then distribute their marks either side according to a different method. Some make it exponentially harder to attain higher points, while others adopt a linear-feeling scale. Tom Stevenson, for example, refuses to give 100 points on principle, and James Halliday almost never scores over 97; conversely, Robert Parker has actually awarded 100 points more often than he has 99. Jancis occupies a mid-way position, with 20 points being genuinely obtainable, but considerably less so than 19.5, and so on. (Below is the distribution of her scores.)

Different publications also vary in how they match quality rank to score. The World of Fine Wine is by definition biased towards higher quality, and operates a stringent system in which a ‘very good wine, with some outstanding features’ can score as little as 14.5 out of 20, in order to increase the resolution at the top end of the scale. Imbibe, a drinks magazine aimed at British restaurants, defies convention by appearing to use the full extent of the 100-point scale, such that a score in the mid-60s is still perfectly respectable, and low-80s becomes outstanding. Having submitted samples to them in past, it made for terrifying reading until I cottoned on to their idiosyncratic mark distribution.

A single score contains no information, therefore, and a pair tells you only one thing: which wine the reviewer considered to be better. You cannot infer how good a wine is from a score without knowing how the critic in question maps their quality ranking onto their points scale. By the same token, scores from different panels within the same publication cannot be compared, because however precisely the editor tries to impose their own house style on the ratings, individual arbitrary factors will always come into play.

Normal maths doesn’t apply to scores. It is common, where a panel of tasters is involved, to give the mean (average) score of the group as an ‘overall’ rating for a wine. This number will be of dubious merit, since we have seen a score can only be fully understood in the context of a taster’s overall mark distribution. The panel might consist of two linear (Parker-style) markers and one asymptotic (Stevenson-style) marker – it is far from obvious in what context we should interpret these average scores. Another related mistake I sometimes hear is ‘this wine is twice the price of another, but not twice as good.’ This is meaningless: since quality cannot be measured numerically, it is not the sort of property that can be multiplied like that. I could disagree and say the better wine was three times as good, and there is no way to settle the matter.

Precision is an illusion. It is very tempting to start subdividing points, since rarely do two wines appear to be identical in quality. It feels natural at the time: ‘I gave 16 points to wine 1, 16.5 to wine 2, and wine 3 is somewhere in the middle, so I really should give it 16.25.’ This is diligent diary-keeping, but as judgement is questionably useful. Tasters are not like machines that we can calibrate before each use. They are under constant threat from Wittgenstein’s private language argument, which entails the question ‘How can a taster know that what they choose to mean by 16 points today is not what they chose to mean by 15.5 points last week?’ The more finely we subdivide our chosen points scale, the harder it is to be certain that we are marking the boundaries in the same place each time.

Words are more objective than numbers. I already mentioned at the beginning why scores are useful. It should, I hope, be clear by this stage that they are inherently limited, and reliant on words to imbue them with much meaning. Quality descriptions (‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘great’) are capable of describing the wine itself in a way that scores, being performances, cannot. Their meanings, although typically much broader than ‘17 points’, are also much more objective – they can be directly understood, without needing to acquaint oneself with a particularly taster’s mark distribution. At this point, we return to the realm of the intuitive, having justified the critics’ regular cry: ‘please read my tasting notes!’

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,415 featured articles

- 274,314 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,415 featured articles

- 274,314 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes