Wine investment – carpe diem or caveat emptor?

19 November 2020 There is so much useful insider knowledge here that we are republishing it free as a warning for anyone contemplating investing in wine.

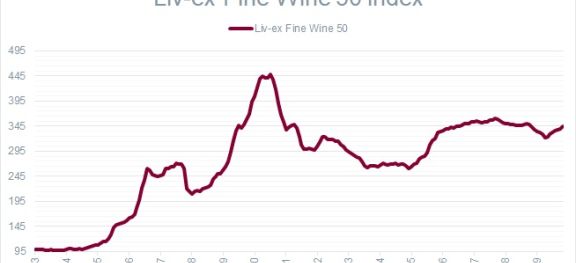

11 November 2020 Matthew Hayes, our man in Burgundy and a refugee from the fine-wine trade, comments on last week's article about Ian Mill QC's rewarding adventures investing in burgundy. Graph above from Liv-ex.com data.

Ian Mill QC’s personal account of his investment success could be inspiring to many, if soulless pecuniary gain is their bent: an almost biblical account of changing not water into wine, but wine into money, and lots of it to boot. However, if the final text is not a smidgen self-indulgent and self-congratulatory, I would contend that such wine-investment success, for the private investor, is largely a thing of the past. And Mill himself admits that his financial gain was almost entirely dependent on a network of privilege and opportunities, unavailable to any but the best connected. The basis of many an investment success is what you know, but Mr Mill’s exemplary success is, and he underlines this, a result of whom he knew and what the relationship was able bring to the party. I accept wholeheartedly that Mr Mill’s intellectual application to the task in hand played an equally handsome role, and paid handsomely in the end.

Today, as ever in wine, the closer you are to the source, the lower price you will be able to pay. I have no doubt that Mr Mill’s collaboration in Cabotte restaurant in the City of London, with its coterie of like-minded souls, continues to offer access to the greatest burgundies (not least, directly via the burgundy producers involved) at prices that the rest of the wine-investing world can only dream of. For example, to cite just two of the domaines he mentions, Roumier and Rousseau, were you able to buy directly from the domaine, you would pay €300 for a Rousseau Chambertin and €600 for a Musigny from Roumier.

I once paid The Wine Society only £600 for a full case of 1996 Rousseau Chambertin but the last time I looked, the Society’s price was upwards of £1,200 per bottle, and just last Friday I was offered, ‘in-trade’, Roumier’s Musigny 2017 at £12,000 per bottle. These are the prices mostly offered to the modern investor. The slack in between is taken up, rightly or wrongly, by the trade, most notably the fine-wine-trading block that has developed so organically with the rise of the secondary market, especially since the early 1990s.

Farr Vintners was founded back in 1978 but the other behemoths of the London broking world – BI, Fine + Rare et al – are creatures of the 1990s. This was an era when wine became a commodity, in the same way as oil or cotton, buoyed not least by some very bright sparks from the financial world such as Gary Boom, founder of BI, who applied modern financial analysis to what had previously been just a gentleman’s business.

Today, with an almost feral mob of brokers feeding off a secondary market which has morphed into a truly international multi-billion pound industry, the individual investor has been squeezed out. There is, in the long run, still money to be made, but not in the proportions that Mr Mill has done.

The wine market has been transformed since 1985. The variety of wines on offer has grown exponentially, as indeed, vitally, has the consumer market to which they are offered. Where once-venerable businesses such as Berry Bros & Rudd, O W Loeb and Corney & Barrow would offer their (even then) limited allocations to their well-heeled clients, demand for the have-to-have wines has mushroomed, and the individual market supply has diminished considerably.

It was a smaller world, well fed and well watered. To their great credit, you cannot rock up to Corney & Barrow with a wheelbarrow of cash and demand an allocation of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. It is highly likely that anyone sage enough to have taken an allocation of DRC in 1985 would still be taking it today if they possibly could. Again, the variety of wines available to the consumer today is legion, but the number of veritable, blue-chip, internationally recognised investment-grade wines has hardly increased; it is just that more people know of them today, as witness the vertical spiral of interest (and prices) in top-end burgundy since 2005. You can add a Masseto here, a Harlan Estate there, but for all they are cherished and celebrated by some, they will never offer the same returns as the historic estates of the Old World have done.

When I was a feral wine broker myself (we are all ashamed of something), I used to joke that I would not get out of bed for a profit of less than 20%. Twenty per cent is nothing compared to what investors in the 1980s who were prepared to wait have made.

I have recently been quietly selling the contents of the cellar of a friend’s father in the north of England. The vendor says ‘I’m too old to drink wine and my children are not really interested’. There was a part he had clearly kept in reserve with an eye to selling, but the vast majority were wines bought to be drunk. To name but two from the traditionally under-performing Rhône, his cache of 1978 Jaboulet Hermitage La Chapelle, bottles and magnums, found a buyer at respectively €1,050 and its double apiece. The vendor’s reaction? ‘They must be mad!’ I doubt he paid a tenner per bottle. The second example is a long array of Hermitage Blanc et Rouge from Jean-Louis Chave (and father) going back to 1982. I stumbled on an invoice from The Wine Society for the 1994s: £15 per bottle, including VAT, duty and delivery. The Society currently offers the Chave 2015 Hermitage Rouge at £250 a bottle duty paid. Full dozens are not on offer.

To my personal disappointment, the senior vendor has kept his rather admirable collection of Mosel and Rheingau Rieslings, on the basis that they will just go on and on. As we say on this Armistice Day, they will not grow old as we that are left grow old. As things stand, with just 1970, a little 1975, some 1982, 1985, 1989 and 1990 bordeaux left to sell I would under-guestimate his return at well over 500%.

In 1995 a bottle of Ch Margaux cost ‘only’ 500 francs, or £600 per case en primeur. In 2019, the same wine was offered at €320 (£3,390 per case), itself a substantial reduction on 2018’s €405. These, I underline, were the prices available to the trade and exclude brokers’ commissions of 10–20%. The advantage of bordeaux is that ostensibly there is at least quantity in which reasonably to invest; you could conceivably buy 20 cases of Margaux 2019, but you would have push out £67,800 in cash.

If you had followed Liv-ex’s erstwhile enthusiasm for the egregious acronym of SWAG – silver, wine, art and gold – as alternative investments, while at the same time keeping a high-profile investor average of 2% invested in wine, then you would be looking at a net, all-in investment value of almost £3.4 million (if £67,800 represents 2% of your investment portfolio). There’s no doubt that you can make money in wine today as an investor, but you now need big money to start with, even with the right connections.

Since Liv-ex was founded in 2000, its Liv-ex 50 index, which tracks the sales performance of the five Bordeaux first growths over the 10 most recent vintages, has performed reasonably well, although it is currently depressed. Since the vintage that broke the mould, 2000, when first growth prices rocketed to €180 ex-négoce, a ‘10-year basket’ bought then would have offered an investor the very healthy return of 250%.

Since then, however, the story is less compelling, with notable troughs. Currently, the five-year return is still a healthy 30%; for the last two years, much less so, at -3% and just 1% respectively. It is worth noting these figures cover a basket of vintages, so pity those sitting on a stash of 2002s or 2013s. These figures are also based on the prices being paid by the trade, not by individual private investors who would have to pay 10–20% on top. And, as the fine-wine trade becomes ever more global, investors have to sell back into the trade to cash in, or play roulette at auction.

At the same time, wine’s global adoption as an investment vehicle has led to wine being hoarded rather than drunk. Wine’s value rises only moderately because of age, per se; the major driver of its price is scarcity. If it is not drunk, it is not scarce, so it will accrue value less rapidly and will just age to maturity and then inevitably decline. This is the rather existential reason that HM Customs & Excise in the UK regard wine as ‘a wasting asset’ so do not levy a tax on any capital gains, adding to wine’s allure as an investment. At what point they might judge that a harmless hobby has become a quasi-vocational revenue source is a moot point best discussed with a qualified accountant. Maybe I should ask a QC.

For all Ian Mill QC’s eulogising the greatness of wines consumed, there is constant reference to price (and Michelin stars) in last week’s article. Some of the most disappointing dinners of my life have been in three-star restaurants. In my experience the size of a restaurant bill is in no way a reflection of its merit, happily inversely so on rare occasions. Similarly, what someone is prepared to pay for a wine is arguably more a reflection of that person than of the wine’s quality. (Surely we can all agree that half a million quid for one bottle of Romanée-Conti ’45 is a couple of bottles short of a full case?) This constant reference to price seems a transgression, even a betrayal of the wines and their makers, not least from someone so deeply and closely connected to them. This is the problem with speculation: speculation is a rather dirty secret, successful or not, best left quietly in the cupboard, ideally gathering interest.

Mr Mill, like me, is over 50. I hope his pension qualms have been resolved, but I feel many of these details might have been best left unpublished, quietly contemplated in a happy, wine-accompanied retirement. Despite the ‘tips to investors’ in the article, there is little here of general use. Although irrefutably an example of impressive personal financial investment success, as his penultimate paragraph points out, it is worth noting the unequivocal disclaimer (he is a lawyer after all) that Mr Mill’s success is based on long-standing personal relationships and access to inaccessible wines.

Patience and passion every investor can acquire, selection less so. Be it the right selection of wines or, for the bluest of blue-chip investment-grade wines, your own selection as a deserving client by those selling them.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,432 featured articles

- 274,133 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,432 featured articles

- 274,133 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes