The wine scene in Sweden

An impressive tasting inspires a deeper look at this fast-growing wine region. Above, first impression of Skåne, a late-afternoon swim in the still-warm North Sea near Båstad. For an extended version of this article, including tasting notes on 41 Swedish wines, see Sweden's emerging wine scene.

It wasn’t exactly billed as the Swedish equivalent of the Judgment of Paris but there’s no question that the organisers of the Swedish Wine Tasting in August 2024, in which 12 pre-selected Swedish wines were pitted blind against 12 European wines, hoped to overturn some preconceptions.

Without going into the mechanics of the judging, which was rather complicated and resulted in a broad range of scores among the many judges – mainly sommeliers and wine writers, both Swedish and international – it is absolutely true that the Swedish wines did extremely and surprisingly well, Kullabergs Immelen 2021 taking the top spot and Sweden having four wines in the top 10.

The 12 Swedish wines had been chosen blind, from the 90 or so wines submitted, by a group of Swedish judges, and resulted in a remarkably limited number of producers. Flädie, for example, had five wines in the line-up, Kullabergs Vingård three. This was disappointing since I tasted other very good wines from other producers in the days following the competition, for example from Thora Vingård or Särtshöga. However, it is possible that they decided not to enter their wines.

The competition was the brainchild of Swedish wine writer Mikael Mölstad, who came up with the idea in 2022 when he was asked to judge some Swedish wines blind alongside some European wines of the same style and price – and he was pleasantly surprised, and encouraged, by his findings. His project team included Sören Polonius, the public face of the competition, who trains the Swedish national sommelier team. (For full details of the wines and the judges, go to The Swedish Wine Tasting website.)

After the event I asked Mölstad what he thought of the results. He replied, ‘Sensational – I was so nervous and must admit that [the possibility that] a Swedish wine would come out as number one was not even a part of my best wishful thinking. I mean, you have to be humble when Swedish newcomers have to compete with some of the great wines from Europe – judged by some of the best wine-tasters in the world.’

The competition had its shortcomings but it made me thirsty for more Swedish wines and I had that opportunity to try more immediately after the tasting, visiting the Skåne region with a group of fellow judges.

Swedish wine’s fast ascent

As Mölstad wrote in his introductory notes on Swedish wine given to the judges, there are ‘very few new wine-producing countries arising out of nothing – but Sweden is one of them’.

The first vineyards were planted in the early 1990s by hobbyists, the first larger ventures at the start of the 2000s. In 1999 the European Union designated Sweden as an official wine-growing region but the country does not (yet) have any official geographical indications nor the wine regulations of European appellations, giving producers more freedom to experiment. ‘Wine from Sweden’ means that the wine is grown and made in Sweden from Vitis vinifera varieties, though some varieties with a percentage of non-vinifera genes (for disease resistance or cold-hardiness, for example) are conveniently classed as vinifera.

According to Mölstad, there are currently around 200 Swedish wine producers, including 70 or so commercial ventures. Collectively they farm about 200 ha (494 acres) of vineyards producing about 500,000 bottles of wine a year – though if sales in Systembolaget, the country’s long-standing alcohol monopoly (created in 1955), are anything to go by, Swedes are very keen on more eco-friendly packaging such as bag-in-box (25% of sales by volume, 14% by value).

Wine consumption is also increasing in Sweden, traditionally described as part of the ‘vodka belt’, fostered by what must be the biggest wine club in the world, Suomen Munskänkarna. According to its chair, Mats Lindelöw, whom I met at a fascinating tasting of non-wine drinks (eg co-ferments of grapes and apples, or apples and hops) at Hotel Riviera Strand in Båstad the night before the competition, it has around 30,000 members in 180 local groups.

Sweden’s wine regions

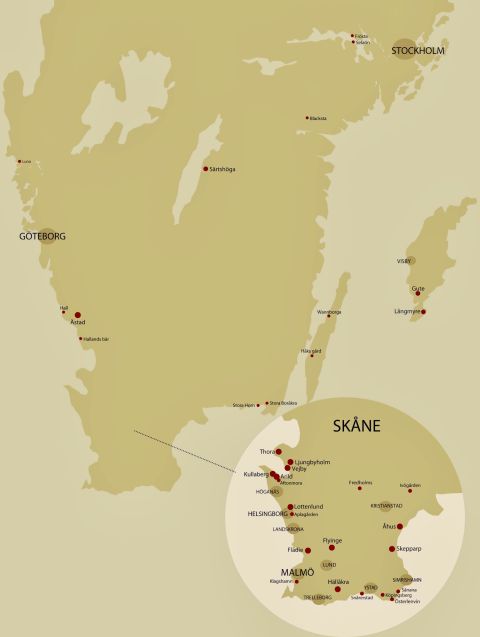

While there are vineyards and wineries on the Baltic islands of Gotland and Öland, in Halland on the west coast and at Blaxta outside Stockholm, the epicentre of the country’s wine is in Skåne. This southern region (see map below) is home to many of Sweden’s vineyards as well as about three-quarters of its commercial winegrowers, as well as some great landscapes, seascapes and beaches.

The train journey from Stockholm to Båstad, in the north of Skåne, was both entrancing and restful, with miles of fields, forests and farms. Sweden is the third-largest country in Europe, after Ukraine and France, and yet has a population of just 10 million, with around 13% of those in Skåne. You can also fly there from Stockholm or Copenhagen but you would miss the chance to feel the open emptiness of this lovely country.

The vineyards are mostly but not exclusively close to the coasts, with particular hotspots on the Kullahalvön and Bjäre peninsulas on the west coast, which are warmed and buffered by the proximity to the North Sea and the influence of the Gulf Stream.

There are several wineries further south, towards Malmö, and on the eastern Baltic coast, which is cooler, with more sand in the soils, leading to typically lighter wines. According to Emma Serna, chair of the Swedish Industry Association for Oenology and Viticulture and owner, with her Italian husband, of Långmyre winery, Gotland in the Baltic is the sunniest spot in Sweden and drier than Skåne.

Björn Odlander, owner of Kullabergs Vingård, pointed out that while Sweden’s northerly latitudes are a challenge to grape-ripening, the wine regions typically enjoy 20% more sunlight than Bordeaux during the vegetative cycle, promoting photosynthesis. Odlander described his location near the top of the Kullahalvön peninsula as a ‘love spot’ with water on three sides to buffer weather extremes and prevent frost, and temperatures up to 35 °C (95 °F) in the summer but no risk of sunburn on the grapes.

Swedish vineyards that have previously been too cool to ripen grapes may be benefiting from the warming temperatures of climate change but they, like those in other cool climates, are also experiencing damaging extremes. The Odlanders, for example, have installed expensive hail nets on some of their vineyards.

Joakim Palm, owner of Ljungbyholm on the west coast of Skåne, believes that ‘Sweden’s challenge is the unpredictable weather: drought one year, lots of rain the next, very windy in 2023, cold during flowering 2024, storms in the summer, hail in late June’. However, he agrees with Odlander that a ‘peninsula climate’ suits vines: the water between the two peninsulas moderates the extremes and prevents spring frost. ‘Summers are longer here, so grapes can hang into October.’

Mölstad predicts that before the 2030s, ‘Sweden will have up to a thousand hectares of vineyards producing some of the world’s best cool-climate sustainable wines’. His emphasis on sustainable is important because this is key to Swedish agriculture more generally. For example, Swedish growers are not allowed to use copper sulphate as a fungicide in their vineyards. Even certified-organic winegrowers in Europe can do this, within certain limits. (The most common alternative approach in Sweden, based essentially on planting disease-resistant varieties – see below – is to spray with a mixture of sulphur and bicarbonate of soda.)

Sweden’s cool-climate grape varieties

Sweden’s cool climate explains the dominance in the vineyard of so-called PiWi varieties, those that have been bred for disease resistance and/or to ripen in cooler climes. While they all include some non-Vitis vinifera genes, they have been conveniently classified as vinifera and can therefore be used to make ‘quality wine’, ie wine with a geographical indication.

The light-skinned Solaris, introduced to Sweden in the 1990s, is far and away the most widely planted variety. Other whites include Muscaris and Souvignier Gris, occasionally Donauriesling. Dark-skinned varieties are far more difficult to ripen and are therefore less widely planted. They include Pinot Noir and Pinot Noir Précoce (aka Frühburgunder in Germany) plus PiWi or cool-climate varieties such as Rondo, Cabernet Cortis and Pinot Nova.

Solaris is so ubiquitous that it was hard to avoid Solaris fatigue on this trip, but the variety can be made in a wide range of styles, from crisp, unoaked, mouth-watering whites to barrel-fermented, multi-vintage or skin-fermented, even botrytised wines. It seemed to me that, left to ripen too long, Solaris becomes just too heavily aromatic and tropical and lacking in freshness, even if one of its advantages is high acidity. When it was like this, oak was not a good bedfellow. The few wines I tasted that included Souvignier Gris, and experiences I’ve had in other countries, made me think that this is one of the most promising PiWi whites. Pinot Nova also looked promising at Kullabergs Vingård, as did Pinot Noir Précoce in the hands of Thora Vingård.

Cellar-door revolution

Another major challenge looks set to be at least partially dismantled. At a dinner after the wine competition, Johan Krallis Anell, the Swedish government’s Food Export Coordinator and the OIV representative in Sweden, explained that, because of the monopoly, winegrowers have not been able to take advantage of burgeoning wine tourism to increase their direct-to-consumer sales at the winery, although some of the better-funded and bigger ones do have their own restaurant, which is a useful outlet. Arilds Vingård, the biggest in Sweden with 38 ha (94 acres) of vines, has a very large and popular restaurant in which they sell about one-third of their production.

Although there have been three public enquiries into the matter, it was only in 2024 that the government agreed to change the rules. It is hoped that the new regulations will take effect in the first half of 2025. There are restrictions, however: the option will not be open to very big companies that process wine, and the sale of wine has to be part of an educational experience such as a tutored tasting, seminar or tour, for which there must be a charge. Victor Dahl, CEO of Kullabergs, believes that allowing cellar-door tastings will encourage many more into the industry and accelerate the development of wine tourism.

In the interim, Systembolaget seems to work reasonably well for small producers, at least locally. While the monopoly’s selection is based on a competitive tender system, Swedish winegrowers do have the opportunity to sell their wines at least in the closest monopoly store, sometimes in several more. I heard little criticism of the system from producers or consumers.

Skåne producers – a tour

Our brief tour of Skåne started on the west coast, on the Bjäre Peninsula. I’ve provided notes on each of the wineries visited, presented in geographical order – starting on the west coast, moving north, then south, and finishing in the east. You’ll find my tasting notes on the wine poured during our visits as well as those tasted blind in the competition at the end of the article.

Thora Vingård

Thora Vingård have a brand-new winery and restaurant and, just as importantly, two very good French winemakers – Emma Berto and Romain Chichery, who met while training in Montpellier. Owners Johan and Heather Öbeg, who lived, worked and met in California returned to Sweden in 2014 to look for a family home and dreamt of making wine.

Today they have 11 ha (27 acres) planted with 50,000 vines, mainly Solaris, from which they make three styles of wine with varying use of oak as well as a sparkling one. They also have some Chardonnay and Pinot Noir trained on individual stakes. (Optimistically, their first 300 vines planted were Pinot.) They are experimenting with Malbec and Cabernet Franc. Certified organic since 2023, the vineyards are also worked biodynamically and regeneratively, and are home to bees and many fruit bushes. An impressive range of wines, so it was a shame they were not included in the competition.

Ljungsbyholms Vingård

Further south on the Bjäre Peninsula is the embryonic Ljungsbyholms Vingård, owned and run by architect Joakim Palm and his wife Annika, head of a local school. They took over the management of their 100-ha (247-acre) family farm in 2019 but most of the land was leased for wheat, oats and vegetables, especially potatoes. They have gradually planted 1.5 ha of vines. They had no experience with farming or wine but they wanted to do something for themselves, something they associated with ‘the good life’ they had seen visiting vineyards in more southerly parts of Italy. One of their two sons is studying agriculture. (They have also bought a share in Matošin winery in Croatia.)

Their 1.5 ha are planted with Solaris, Rondo, Cabernet Cortis and Regent. Palm highlighted the problem with the parts of their land that are heavy clay, more suited to cereals: the Solaris ‘suffocated’ and the vine roots could not penetrate the soil unless drainage was installed. They are planning to plant another 5,000 vines this spring, and they have their own distillery.

Arilds Vingård

Still in the west, at the base of the Kullahalvön Peninsula is Arilds Vingård, Sweden’s biggest producer, owned and run by Annette and Jonas Ivarsson, who met at university and bought their 18th-century farmhouse in 1997 to renovate as a family home. Finding a vine by the house inspired them to plant their first 5,000 vines in 2007, with Annette (below) studying at Geisenheim and Freiburg. As Annette said, ‘making wine is too expensive to be a hobby’. To fund the wine business they opened a hotel and restaurant.

Today they have 38 ha (94 acres) of vines (18 ha not yet productive), including 12 ha of Solaris, a big and popular restaurant, a 37-room hotel and glamping in the parts of the vineyard that are not good for vines. Their Californian winemaker Joe Roman came here because he wanted to work in a region free of agrochemicals. They have farmed organically from the outset. Given the scale of the operation, some of the vines are machine-harvested but they keep some vines for manual harvesting because the activity is so popular with visitors, who pay for the pleasure and turn it into a harvest party. They don’t export their wines because they want to limit their carbon footprint. We tasted only barrel samples during our visit but the oaked Pinot Noir Précoce looked promising.

Kullabergs Vingård

Kullabergs Vingård, on the Kullahalvön Peninsula, is a sophisticated operation. It has been owned and run since 2013 by Björn Odlander, a leader in biotech and medical technology, and his architect wife Paulina Berglund. Their Swedish winemaker Felix Åhrberg (below, with Björn Odlander on the right) trained and worked in Germany and Austria and was sporting Lederhosen on the day we visited. They were all on a high after the results of the tasting competition, with several bottles of their very good sparkling wine sabred by Åhrberg on our arrival. They also have a South African consultant.

The new winery, designed by Berglund, is a stunning shrine to wood, especially viewed from inside. She explained that very thick untreated wood has better fire-resistance than steel.

They have 18 ha (44 acres) of vineyards, farmed organically but not certified, mainly Solaris (some planted by the previous owner) but also Souvignier Gris, Donauriesling, Muscaris, Pinot Nova and Cabernet Cortis. There are many fruit trees and bushes round the vineyard to protect from the wind and provide alternative nourishment for the birds. They also have a test field with 22 varieties. Harvesting is done by machine because of the labour costs. Our visit included a terrific lunch to celebrate crayfish day, with crayfish hats obligatory. Their 2022 Immelen Solaris was a great accompaniment.

Lottenlund Estate

Lottenlund Estate, owned and run by Tina Berthelsen (below) and her partner Manfred, is further south, near Helsingborg. Berthelsen worked in sales and marketing in the fresh-produce industry for 17 years but decided to move across to wine after they visited Montalcino in 2010. They already had the house and the land, an extra 10 ha (25 ha) bought to protect them from potential neighbours, and in 2016 they planted 4 ha with vines bought in Freiburg.

They now have 3.5 ha in the Bjäre Peninsula and 7 ha around the house and winery, all farmed without pesticides. Both sites benefit from proximity to the sea. All their vines are PiWi varieties, 60% white, 40% black grapes, a total of 45,000 vines: Solaris, Muscaris, Souvignier Gris, Donauriesling, Cabernet Cortis, Monarch and Pinot Nova.

Winemaker and viticulturist is Denmark-born Jacob Grinsted, a former IT project manager who studied viticulture in Piacenza, Italy. He described working in Sweden as ‘living on the limits of winemaking’, with just 1 kg of fruit per vine. Unlike the peninsula growers, they experience frost – in October not in spring. Their vines, apple orchard, beehives and chickens are all immaculate, beautifully tended. They also make excellent gin and vermouth.

Flådie Mat & Vingård

Further south towards Malmö is Flådie Mat & Vingård. Owned since 2020 by Håkan and Carina Wikholm, the original farm dates from the 1870s but was transformed from 2003 onwards by restaurateur Nils-Bertil Hansson into a hospitality destination with a hotel and restaurant. His son Martin established the 3-ha vineyard and winery. The first vines went in the ground in 2007 and the first wines were made by Murat 'Murre' Sofrakis from Klagshamn, whose winemaking skills put them on the map. COVID was the ruin of the business, which went bankrupt.

The Wikholms have another farm and vineyard north of Skåne in Assmåsa, north of Ästad, with 20,000 vines planted in 2018. They are working out how best to use the fruit from the two locations, but the wines are all currently under the same brand name. Their new Portuguese winemaker Gonçalo Santos (above) started in 2023 so this is still a work in progress but it is pretty remarkable that of the 12 Swedish wines chosen for the competition, five were from Flädie.

Flyinge Vingård

In the more central part of Skåne, north of Lund, historically famous for horse breeding, is Flyinge Vingård. Owned by Magnus Oskarssen (below), whose family is from Malmö and whose money is from real estate, the winery has 2 ha (5 acres) of Solaris, farmed organically, and 500 Rondo vines not yet in production. Their winemaker, Jasper Friberg, also makes wine under his own label (see below).

Oskarssen bought the land in 2009 with little knowledge of viticulture or wine. The soil is sandy clay over silt, and, as it is close to the river, the land was too wet so they had to install drainage. While they lack the buffering effect of the coast and are at risk of frost, which was particularly damaging in 2019, it’s generally warmer and less windy here, giving them very ripe fruit in the best years. Since vintages are unpredictable, they also make a multi-vintage wine.

Oskarssen says they are ‘still in the learning phase’ and if they started again, they would plant the rows further apart because at 59° north there is a lot of shading between the rows.

Jesper Friberg

Jesper Friberg (below) does not have his own winery but tasting his wines with him at Flyinge, where he is the winemaker, was deeply inspiring, not just because of the quality and distinctive style of the wines but because he embodies a model of production that had seemed to be missing in our winery tour: a young person without financial backing making wines from grapes bought from other young growers or from rented vines. He has 0.5 ha (about 1.25 acres) of vines planted with eight varieties that he does not own but has been looking after since 2023. He uses no sulphur on the vines, only herbal teas, insisting that the key to a healthy vineyard is to control vine vigour and ensure a good airflow through the canopy. He’s trying to encourage young people to grow grapes because there are just not enough to match the demand.

To fund his wines, he works 2–3 days a week as a roof thatcher. He, like many others, mentioned the importance of Murat 'Murre' Sofrakis, with whom he worked at Klagshamn and who gave him the chance to make is own wine with Klagshamn fruit. (Unfortunately we were not able to visit Sofrakis because he had no wines to show.)

Skepparps Vingård

The only winegrower we visited on the east coast of Skåne, Skepparps Vingård, is in Brösarp, just north of Kivik in Österlen, Sweden’s apple kingdom. Grapes ripen typically two weeks later than in western Skåne. Owner Bengt Åkesson (below), who worked with wine in the hospitality business, planted his first 7,000 vines in 2011. He now has 6 ha (15 acres) of sloping vineyards around the winery on sandy soils, just 2 km from the sea, and another 5 ha on flatter ground in Kivik. Actually seeing a slope was a novelty on this trip. All the vineyards are planted with PiWi varieties, including Solaris, Merzling, Souvignier Gris, Rondo and Cabernet Cortis. The area does get some frost in spring but Skepparps use a temperature alarm to tell the team when to go out with the Frostbuster.

There is a strong focus on sparkling wine and Åkesson advises other producers making this style. He also produces bulk wine and blends and bottles wine from, for example, Spanish producers who have won a tender with Systembolaget. The winery holds a huge annual wine festival in late August.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,406 featured articles

- 274,946 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,406 featured articles

- 274,946 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes