Part I

If asked to put a dollar value on a part of our living world, a funny thing starts to happen to our thinking. I think the best way to imagine this is by that all too familiar scenario played out by parents everywhere. If asked, say, ‘what is money?’, the rabbit hole posed by the child doggedly asking ‘why’ leads the adult to watch that last thin veneer of arbitrary justification simply melt away. Such is the truth about many things in our natural world and how it is that we try to appreciate them; they escape the metrics that we try and set up, their essence is one that escapes our understanding. In my professional and academic life, I’ve seen this happen when people try to assign a dollar value to our ecosystems and their innumerable services, but I’ve also seen it when grape growers are forced to reckon with the loss of vines that once held some portion of time’s indelible mark. How can we begin to grapple with what is lost, with what was had?

We at Brooks Wines were recently faced with this problem when someone drove their car through our estate vineyard, tearing out several dozen of our vines—some of the oldest original plantings in the Willamette Valley, Oregon (USA). And though it was the insurance companies that had to settle the question of how to “properly” define and compensate for their destruction, money, we understood, could not begin to replace 50 plus years of character inherent to their roots.

I think this incident greatly illustrates our relationship to our estate vines and why we forgo any question of replanting them for younger, more productive ones; should we be forced to lose a limb, we would prefer that someone else should do the chopping. Though this remains a hair dramatic, I don’t believe that it is entirely hyperbolic. We, like most growers, view our vines as our greatest asset and point to the vineyard as the source of our craft, quality and passion. And as stewards of some of the only old vine Riesling in the Willamette Valley, we feel that we are obliged to preserve those that we have under our care. To put it another way, like the character Chef in Apocalypse Now (1979) witnessing the army throw beautifully marbled prime rib into pressure cookers, ripping out our vines would be the antithesis to what we hold dear.

Part II

The origins of our estate begin with Don Byard, one of Oregon’s original wine pioneers. Like most who start in the industry, Don had a full time job when he and his wife, Carolyn, purchased the 20 acre (8.1 ha) orchard in the Eola-Amity Hills AVA (est. 2006) in 1973 and began replanting it with vines. The spark for such a decision, as Don will tell you, came from his discovery of wine, and particularly that of Riesling, during his service overseas in Germany. The timing for the start of their adventure could not have been better, as at that time, the idea that Oregon was too cold for grapes was being challenged by a group from UC Davis who saw the Willamette Valley as the perfect location for cooler ripening Pinot Noir and Riesling.

Don chose the location with this in mind, choosing a beautiful South-East facing parcel for want of the gentle ripening posed by the early morning sun and by the cooling evening breeze that came from the nearby Pacific Ocean. The site is special in another fashion when looking at the soil. As Claire Jarreau, our Associate Winemaker explained, unlike elsewhere on the Eola-Amity Hills, which contain primarily marine sedimentary rock, our estate is composed of Nekia, “a shallow, rocky, and well-draining volcanic clay composed of weathered Columbia River Basalt”. This is beneficial to us as winemakers with an eye to a changing climate by the fact Nekia “has proven to offer greater water-holding capacity than their marine sediment counterparts”. These volcanic soils are incredibly valuable for their ability to “better retain acidity in the fruit chemistry”, which is “important for us as winemakers, as it is the single greatest contributor to allowing us the ability to work in a more hands-off, natural way while still producing vibrant and clean wines”. On top of this, it allows the wine to retain a certain freshness during high temperatures, something that is especially important given the fact that this year’s June temperatures have already broken all historical records in the Willamette Valley, reaching 117 ℉ in nearby Salem (47 ℃). Given the reality that this and other effects caused by the climate crisis are sure to impact our area, we view this soil character as a crucial element to our continuation and style of winemaking.

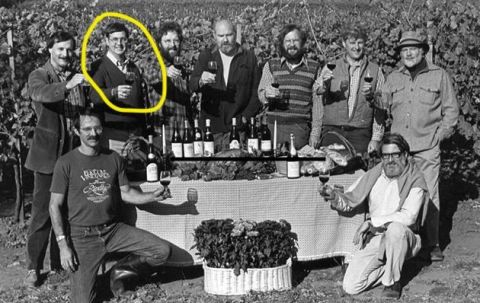

Following their appraisal of the site and purchase, Don and his family planted 5 acres of Pommard clone Pinot Noir and 5 acres of Riesling in 1973 , followed by 0.9 acres of Pinot Gris in 1979 and then another 9 acres of Pinot Noir (777 and 115) in the late 90’s on grafted rootstock. In 1980, when Don and Carolyn “were growing more grapes than [they] could drink”, the two created their label, Hidden Springs, with a group of friends in the same prune drier where we would later move our winery some 35 years later. To complete the circle, it begs mentioning that two of their daughters, Heidi and Heather, remain some of our oldest employees and serve wine sourced from the very hillside that they helped their parents plant as children.

We are not the first ones to consider the value of our vines and whether we should make drastic changes for the sake of future vintages, because Don too lived at a time when many winemakers were tearing out their original vines or regrafted them once it was found that the Willamette Valley was extremely well suited for Pinot Noir—83% of the valley’s production.

Like any decision, there were benefits and trade-off’s associated with either choice, but, after careful consideration, Don decided to stay true to his love of Riesling and kept his original plantings. And so, just as any decision can have unforeseen consequences, this was one of the many decisions that led us to be in the care of some of the oldest Riesling vines originally planted in the Willamette Valley.

The introduction of Brooks Wine’s to the vineyard began with my father and our founder, Jimi Brooks, one of the many ‘second-wave’ winemakers that emerged in Oregon after those like Don took a gamble and forged the way. After my father began Brooks in 1998, he began searching for a parcel containing old vine Riesling; his favorite varietal for its complexity and ability to show off the terroir if under the care of thoughtful and skilled winemakers.

Needless to say that when the two met, Don took an immediate liking to my father, partially due to their shared appreciation for what they considered to be an undervalued and misunderstood grape. I don’t think that Don’s affinity for my father can be understated, especially by the fact that outside of selling him fruit, he agreed to switch from conventional agriculture to biodynamic at my father’s behest in 2002; achieving Demeter certification in 2013. However, what began as a promising relationship was cut short by my father’s unexpected passing in 2004. Don, in a decision that I had not appreciated until much later, offered to hold his service amongst the very vines that my father worked and had once hoped to purchase. To me and my family, Don, his children, and later grandchildren, these vines are not a part of the scenery, but remain omnipresent features to ourselves and our integral memories; an intimate connection to the past, where we once measured our height by where we reached upon the trellis, by the fact that our very hands may have planted them, or that our fathers may have pruned them and given them their shape. Like a measure of time, we remember our loved one’s birthdays by when the buds break or by the time of harvest. Little may be left of the time that has passed, but we are at least able to admire the form that the vines have taken by the many hands that came before us in its passing.

Part III

Up until now, we’ve been lucky with our vines—incident with the Ford Explorer, notwithstanding—but the future remains uncertain. With a warming planet and its effects on how they have already impacted our area and industry—including a cancelled vintage from smoke damage caused from historically destructive fires in 2020—we as stewards have good reason to be concerned. Our deep appreciation for the fruit may be checked by the influx of higher temperatures, less rain and further damage posed by fires, pests and wood disease; the latter being already present in our vineyard and is “perhaps the greatest threat to old vines in Oregon”, says Jarreau.

But we remain proactive and are working always to improve the quality of our work. Steps that we plan to implement in order to improve our care includes the developing of our site through planting of trees, expanding and diversifying our already large garden space, as well potentially incorporating some sustainable husbandry practices that would help to service the property and vineyard. We see these efforts as a way to expand our holistic approach to the land and vineyard care that will have real impacts on vine health, the quality of the wine we produce as well the ecosystem that they are a part of. This is crucial given an increasingly uncertain future, because we cannot expect to make wine that truly shows the quality of the land and our practices without first looking to bettering our system.

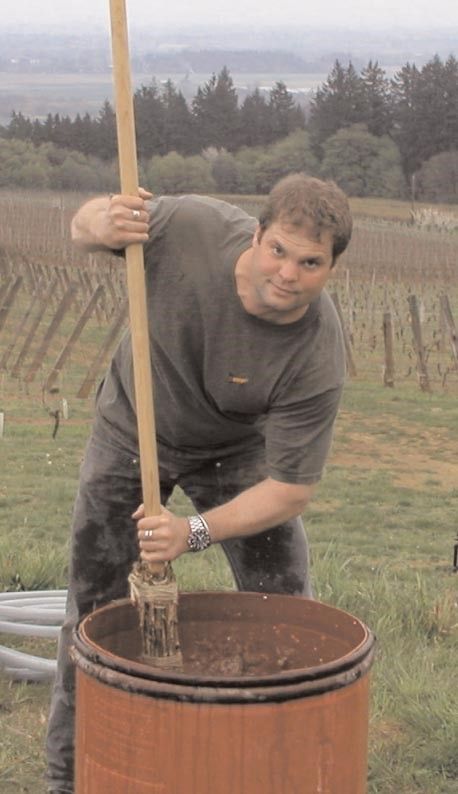

Presently, labels focused on old vines include the bottling of old-vine Pommard -- a consistent favorite by our Head Winemaker Chris Williams for their seeming “Old World feel [and] quintessential showcase of Pinot”; Estate Pinot Gris; two Rieslings, a dry style called Brooks Estate and a medium sweet, bright acid spatlese style named Sweet P, embarrassingly named after a younger me; one of our oldest labels, Rastaban, a loyal and approachable blend of all of our Pinot blocks; as well some of our estate’s Riesling blended into our reserve Riesling label, Ara.

Part IV

It’s difficult to discuss the future of grapes and the world with any certainty, and yet, such is the nature of raising vines. I think this can be best summed up by what a Corsican olive farmer once said to me of his charge, that ‘they are planted by the grandparents and enjoyed by the grandchildren.’ I’ve heard it said by some that planting is an act of love, and in some ways it is: it’s an act for those that we have not yet met, like planting a tree whose shade or fruit we know we may not come to enjoy. Hearing this farmer, I was immediately reminded me of our vines, wherein our stewardship stands at the crucial meeting point between past and potential future.

Given a changing world and market, replanting is a valid question. We know that, should we ever entertain the idea, intentionality will be the only way in which we can justify love’s labour’s lost and the further work it would require. It’s why we chose to replant those destroyed vines, in the hope that one day, someone will be able to enjoy the fruits of our labor and intentions.

The photo are all provided by Pascal Brooks, but the source of the photo with Don Byard in is Prince of Pinot and the main photo of winemaker Chris Williams is by photographer Carolyn Wells Kramer.