Contrary to popular history, The Willamette Valley’s fine wine industry did not start when David Lett planted Pinot Noir near Dundee in 1966. The Valley’s wine origins go back much further than this, and echoes of that story can still be found tucked away on a hill, just northwest of Portland near the town of Forest Grove. Instead of driving down to Dundee to check out the newest vintage of Pinot Noir, wine drinkers of 19th century Portland might have gone west to the loess hills of Forest Grove to pick up bottles of award winning Chasselas from Reuter Winery. Today, that history is almost forgotten, the thread cut by massive disruption of prohibition in the 1920s and again by the rapid proliferation of Pinot Noir in the valley over the last few decades. But there was a moment in the 1960s when that history was rediscovered by a forgotten father of Oregon’s modern wine industry, and again today by one of Oregon’s most talented young winemakers. That history lives on in the old forgotten vines planted by Charles Coury and the wines of Jeff Vejr.

Part 1: Charles Coury

One can’t understand the history of the Charles Coury vineyard without first understanding the man himself, for the vineyard embodies not only his dream of American cool climate viticulture, his commitment to developing Oregon into a world class wine region, and his appreciation of its history, but also his fatally outsized ambition.

Originally a trained meteorologist, Charles was bitten by the wine bug during the Korean War and entered UC Davis in 1961 to earn his Masters in viticulture. Within the early Willamette community, Charles would become known as a brilliant yet stubborn and difficult man, and these qualities are apparent even during his time at Davis. His Master's thesis “Wine Grape Adaptation in the Napa Valley” suggested that cooler climates were better for growing certain grape varieties, which flew in the face of accepted teachings at the institution. Charles was nevertheless an extremely successful student and was awarded a stagier at INRA- France’s government body that experiments with and catalogues grape varieties- and worked on the initiative to help redevelop the vineyards of Alsace following the devastation of WW2. This experience deeply impacted Coury’s future efforts in the Willamette. Not only was he witnessing first-hand the recovery of a cool climate wine region, but also the rigorously experimental approach that INRA took in matching grape to climate.

Charles moved to Oregon in 1964, and immediately began a process of research and exploration across the Willamette. Continuing with his academic mindset, he visited the archives at Oregon State University (then known as Oregon Agricultural College) and was shocked by the variety of grape varieties and farming techniques that were recorded by the pre-prohibition farmers of the 19th century. In contrast to Diana Lett, wife of David Lett and co-founder of Eyrie Vineyards, who reportedly said “it wasn’t easy being a pioneer back then,” Charles Coury claimed “This is no pioneering effort. This is a Renaissance. They were doing this 75 years ago. We are just rediscovering what was forgotten.”

Charle’s spent the next year searching for the best vineyard land. After asking local farmers in the area, he learned about the old Rueter vineyard in Forest Grove. Coury spoke to the two surviving Reuter daughters still living in the area, who told him more about the grapes planted and their award-winning wines. The land was currently for sale, the grapes long pulled up, but the original house was still standing, and the orientation and aspect of the slope remained ideal. In 1966, just a few months after David Lett began planting Pinot Noir (among other things) in the red hills near Dundee, Charles Coury began replanting the old Rueter Vineyard of Forest Grove. Given the incredible history of the site, it’s easy to imagine that Charles thought he was making the safe bet.

Part 2: Charles Coury Vineyards

Like all the early pioneers in the Oregon wine renaissance of the 1960s and 70s (this seems like a compromise that would have appeased both Lett and Coury) there were a lot of financial struggles in starting Charles Coury Vineyards. But whereas his colleagues started modestly, planting small vineyards and building low tech wineries, Charles had no desire to go slow. Armed with his conviction in the possibilities of cool climate viticulture, and his knowledge of the thriving wine industry that had once existed where he stood, Charles rapidly developed his winery, purchasing new stainless-steel tanks (which had been very popular in Alsace during his time there) when his colleagues were still making wine in tubs. To make this possible he took on several investment partners and started a grape nursery.

The grape nursery business both enabled and pushed Coury to plant a diverse variety of grapes in his vineyard, as he needed to propagate all the material. Charles was soon planting diverse clonal selections of Semillon, Chardonnay, Chasselas (perhaps a nod to his acknowledged forbearers in the region), Savagnin Rose, Flora (an extremely rare cross between Gewurztraminer and Semillon), Riesling, Pinot Blanc (including a rare, mutated clone called Pinot Gouges, taken in the early 1960s from Domaine Henri Gouges in Burgundy), and Pinot Noir. The list goes on much longer, but it is worth noting that Pinot Noir was not particularly privileged among any of the other cool climate varieties that Coury was experimenting with. This nursery was pivotal in supplying many of Oregon’s first wineries with plant material.

Unfortunately, Coury’s ambitions were quickly mired by the realities of the nascent industry. Coury’s ambitious investments into his vineyard and winery, coupled with several failed contracts at the nursery, quickly put his business in dire straits. In 1977 Coury was pushed out by his financial partners. The vineyard would be sold four times between 1977 and 1981, and for the rest of the 1980s the land was owned by a bank. In 1992 the vineyard was purchased by its current owners, the Stoyanov family, who renamed it David Hill, a legacy name for the property from the time of prohibition.

But, it is in part because of this early fall from grace that there are still echoes of earlier histories of Oregon wine at the Charles Coury (now known as the David Hill) vineyard, both of that fragile renaissance in the early 1970s, and Coury’s attempted excavation of the forgotten pre-prohibition culture. Ironically, history is often better preserved by apathy than any sense of preservation or glorification. A version of this story essentially played out with the Charles Coury vineyard: tucked away just west of Portland, far from the gravitational center of Willamette Pinot, the diverse plantings avoided being ripped up simply because it was not worth doing so. Instead, the Stoyanov family elected to expand the vineyard with Burgundian and Californian clones of Pinot Noir and throw the amazing diversity of old vine, own rooted white grape varieties into anonymous white blends. Who knows what would have happened to these vines if Coury had been just another success story in the modern history of the Willamette Valley, but it is hard to imagine that The Valley’s transition into a near Pinot Noir monoculture wouldn’t have been reflected in his own vineyard, just as the initially more diverse plantings of all of his contemporaries have as well.

It is tempting to think that the second reason this historical vineyard has managed to survive was Coury’s clever appreciation for the wisdom of Oregon’s first winemakers, but it was probably just luck. Like many of the original families that replanted the Willamette Valley in the 1960s and 1970s, Coury planted vines on their own rootstock. But, whereas the rest of his contemporaries planted further south on the Jory soil that The Valley is now famous for, Charles’ decision to plant in the traditional, loess vineyard land of the northwestern part of The Willamette has proven crucial. Whereas almost all the original own rooted plantings of the central Willamette have succumbed to Phylloxera, the Coury vineyard’s old, own rooted vines are still going strong, protected by the sandy textured, loess soils of Forest Grove. It is unlikely that Coury, the climate obsessed meteorologist, was thinking about this when he purchased this vineyard land, but the decision nevertheless proved fateful.

The quick demise of Coury Vineyards before the solidification of the Willamette Valley around Pinot Noir and his decision to plant further afield in the loess hills of Forest Grove, resulted in his vineyard becoming a sort of time capsule, a crystallization of not only of a nascent Willamette wine industry, but also a time when its future was far from certain and many possibilities beyond Pinot Noir were being contemplated.

Part 3: Rediscovering What Was Forgotten

Although never really lost, the potential of these amazing old vines, some of the oldest and rarest varietal plantings in the United States, was once again recognized in 2013 by Barnaby Tuttle of Teutonic Wines, and Jeff Vejr, a young wine lover with experience making old vine wines in Spain and France. Barnaby, inspired by Germanic wine culture, was interested in sourcing the Chasselas and Silvaner grapes planted at a vineyard in Forest Grove. He brought his friend Jeff along for the ride.

Barnaby and Jeff quickly noticed the huge vines located just adjacent to the winery, much larger than anything else at the property. They asked the vineyard manager, who nonchalantly replied, “that’s just our Semillon.” They enquired more and learned that they were in fact standing on what had been the Charles Coury vineyard, and that they were surrounded by many of his original plantings. Of what exactly, the current winery only had vague ideas. But Jeff was hooked by the mystique. His love of old vines had been engrained by his time spent in the Languedoc and Priorat, but he never imagined he would find such a treasure so close to home.

Jeff founded Golden Cluster that same year. The project is centrally a wine brand, but it is also an exercise in ampelography and history, dedicated to recovering the legacy of Charles Coury and cataloging Coury’s original plantings. Jeff makes several single varietal wines from Coury’s original plantings, highlighting the diversity and sense of experimentation that is often lost in the story of Oregon’s modern wine industry. All offer similar levels of depth and intensity, nakedly demonstrating what is only possible from fruit produced by old vines. The wine he has become most known for is the old vine Semillon, a dry style made at full ripeness (although in 2019 he experimented with a low alcohol, Hunter Valley style). He also makes some of the only varietal Flora and Savagnin Rose wines in the world. In the best vintages, Jeff releases a wine called ‘the first row’ which comes from the scion block that Coury planted to propagate his nursery. It includes 6 different grape varieties and dozens of different clones, including 22 different Chardonnay clones and the Pinot Gouges that Coury “imported” from the eponymous Burgundy estate.

Vejr, inspired by Coury’s more experimental approach, is more broadly attempting to re-open the question of what Oregon wine can be at its best (i.e. not necessarily Pinot Noir). He is making some of the most interesting, and most importantly delicious wines in Oregon, working with an incredible variety of grapes such as Saperavi, Sagrantino, Garanoir, Regent, Isorka, Syrah, Kerner, Sauvignon Gris, Agria, Fiano, Blaüfrankish, Rkatsiteli, across numerous labels. But the Golden Cluster wines from Coury’s lost old vines remain the heart of his work, a vinous embodiment of a forgotten history of the Willamette and the hope for a more diverse, delicious future.

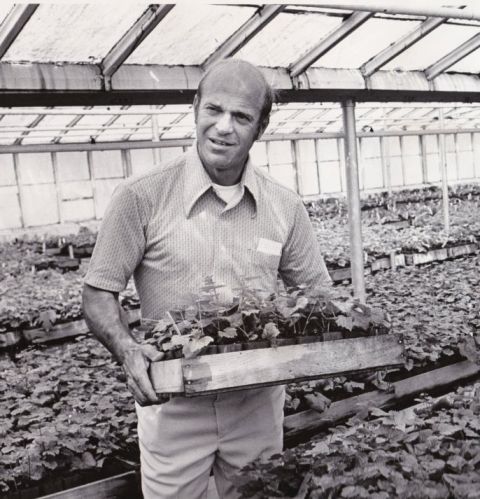

The photos are provided by Lewis Kopman. The photo at the top of the article is Lewis Kopman with a bottle of Golden Cluster Sémillon.