'My name is Adrianna Catena. I’m a historian and fourth-generation vintner, currently living in North London with my partner and sons. I grew up in Argentina, spending my summers at the family winery in Mendoza, tormenting my father, Nicolas Catena Zapata, with a habit of climbing up and leaping across the steel tanks. I moved to California in 2002, graduating from UC Berkeley with highest honors and the Departmental Citation in History. In 2008, after a year in northeastern Senegal working with the NGO Tostan, I settled in the UK, completing an MPhil and DPhil in History at Balliol College, Oxford. In 2010, I co-founded El Enemigo Wines together with winemaker Alejandro Vigil, a project I am deeply proud of. I’m always looking for ways to weave history and wine together. In 2017, I collaborated on the creation of Catena Zapata’s Malbec Argentino label with Stranger and Stranger, the first wine to narrate the history of a varietal (in four allegorical images) on its label.

'Between 2017 and 2020, I held a Leverhulme Early Career Research fellowship at Warwick University. In 2020, Covid scrambled plans and perspectives, moving me to take a larger role in the family winery. It’s been a mad but fulfilling year. For Women’s Day 2021, I was included in Vivino’s blog post: ‘Ten Inspiring Women to Celebrate on International Women’s Day,’ (along with the amazing Shakera Jones and two women I admire greatly, the Lopez de Heredia sisters). The future, for me, is (always) about learning, finding new ways to share and participate in the wider wine community.

'As a historian in a family of winemakers, I jumped at this opportunity. The topic is far from my own area of expertise (in early modern Spain and the Atlantic) but gave me a first chance to delve into our family’s work, experience, and trajectory from a historical perspective. It gave me occasion to remember my grandparents, listen to my father’s stories, and boast a bit about my sister. I also love old vines (who can resist them?), and it was a joy to write this piece. Thank you!'

See our WWC21 guide for more old-vine competition entries.

Caruso in the Library

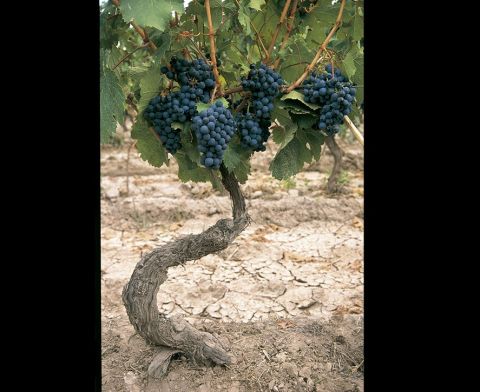

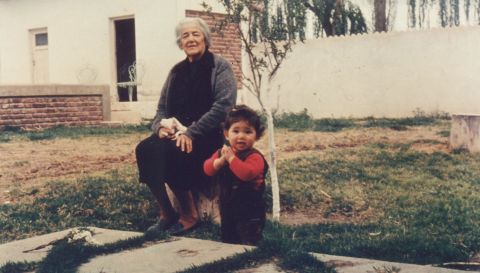

Around 1928, in Mendoza, a winemaker fell in love with a schoolteacher. It was an odd pair. He was an outdoors man, fun and outgoing; she was studious, shy, meticulous. He liked dogs, Caruso, and long, loud lunches; she loved books, numbered lists, and polished shoes. They married, had four children, and remained stubbornly different until a car accident took her life three decades later. Every Sunday for the next thirty years, he visited her grave with flowers (building a rosarium, that still survives, to this end), before heading over to the old Italians’ Club for cards and vermouth. Towards the end of his life, Domingo purchased an old vineyard, planted around the time he’d met Angélica (pictured above), and named it for her.

I don’t think it would have mattered much to my grandmother, whether a vineyard was named after her, but I’m sure she would have been deeply proud of the work this one inspired. The wines from Angélica became a moving force in the recognition of Malbec abroad when the 1996 Catena Malbec was selected #1 by the Wall Street Journal, in the first article to cover Argentine Malbec for a major world newspaper1. The vineyard would reflect Angélica’s legacy in other ways – the academic, investigative vein she gave our family, the love of learning – launching our research into Malbec with the Catena Cuttings, the largest collection of Malbec plants in the world and founding project of the Catena Institute of Wine (CIW).

As they near their centennial, the vines at Angélica are, quite simply, beautiful. The small, dark blue grapes still make enthralling wines, delicate and perfumed, with hints of ripe plum and sweet, generous tannins. The thickened trunks, twisted by the weight above, beckon you closer. Every visitor, without fail, stoops to touch them. The soil is loamy, gravelly, well-drained. Underground, deep root systems, some beyond two metres, speak to the slow passing of time. Here past meets present and future; in a natural response to water stress, thousands upon thousands of fine roots have appeared. They’re looking for the water that once regularly flooded the riverbanks – flooding we haven’t seen for decades. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Angélica

An area traditionally esteemed for the quality of its wine, the valley of Lunlunta takes its name from an indigenous Huarpe word for the sound of underground water, of water running over stones – a reference, perhaps, to the round alluvial stones found across the region’s subsoil. At 920m in elevation, the vineyard’s 70 hectares extend west from the main road to the river, opening onto a sprawling view of the Andes. The earliest reference to its existence appears in the 1924 viticultural census, and we can assume cultivation began a few years earlier. The vines tell the rest of the story. Planting began next to the road, conveniently close to the railroad that had revolutionised the region some decades earlier. Over time, the vineyard was gradually extended by massal selection – a few more rows every couple of years – advancing in this fashion towards the river Mendoza, with the final lots or cuarteles grazing its waters.

The quality of lots 18 and 20 bear witness to the gradual selection process, the work and wisdom of those who first cared for it. The vine population is also highly diverse – a genetic treasure. Lunlunta is exceptional in this sense, home to some 2500 hectares of old, ungrafted vines planted, like Angélica, at the height of Malbec cultivation in the country.

Malbec: a family history

The story of Malbec in Argentina is well known; in 1853, lured by the future Argentine President, Domingo F. Sarmiento, French agronomist Michel Aime Pouget began work on a large nursery and garden in Mendoza, baptised the ‘Quinta Normal’. To populate his venture, Pouget would introduce a variety of French varietals (by way of Chile), including the first vines of Malbec. The novel grape adapted itself particularly well, with a swift and dramatic increase in cultivation just as phylloxera ravaged Europe. Where the French and Italians were forced into grafting onto North American rootstocks, Argentina, phylloxera-free, could continue propagating its vines through massal selection. By 1930, the country boasted an annual per capita consumption of 66 litres of wine, satisfied in its entirety by national production, over 2/3 of which came from Mendoza, where 51.5 percent of vineyards were planted with Malbec.

Some of this genetic material was diluted in the course of vine pull schemes introduced during the 1960s and 70s, as domestic demand shifted towards jug wines. Across Mendoza, French varietals including Malbec, Cabernet, and Semillon were replaced with the higher yielding, local Criolla and Cereza varieties. The country’s romance with the black grape of Cahors was long over by the time my grandfather purchased the vineyard in the early 1980s. His eldest son, Nicolás Catena, was running the family winery, and he didn’t think much of Malbec either. Saturday evenings, everyone brought their loyalties to the table: Nicolás drank Cabernet, his father Malbec, and his grandfather Bonarda. It was love, and then a bit of serendipity, that eventually changed my father’s mind. The story, in our family, goes something like this:

During a last visit to Angélica, in his final days, Domingo enjoined his son not to forget Malbec. It was out of devotion, then, that my father revived this old, neglected vineyard. But he had neither hopes nor ambitions for it. Years later, for the harvest of 94’, he engaged Tuscan winemaker Atilio Pagli. On a drive to the winery, my father talks relentlessly about Super Tuscans and his dreams of growing Sangiovese in Argentina. When they arrive, Atilio walks over to a crate of grapes from Angélica, en route to be destemmed, and falls head over heels with Malbec. He can’t stop asking questions, about everything: the soil, microclimates, the age and origin of the vineyard. He asks to be taken there immediately.

Trials and tests followed. Pagli worked tirelessly, subjecting the fruit from different parcels at Angélica to varying fermenting styles. He went for sangria, once at a terrifying 40%. And it worked! Some time later, at a second meeting with my father, he relayed his findings. ‘I have good news and bad news. You’ll never make a great Sangiovese here. But: what you have in Malbec is unique and extraordinary.’ As is often the case with such fateful episodes, recollections can differ. In Atilio’s version, the climactic moment is more dramatic, set at night and over dinner, with a small and select group of winemakers that would include Paul Hobbs and Pedro Marchevsky. Towards dessert, Atilio gives an earnest speech in defence of Malbec – there is potential here, he declares, for a ‘national grape’. The table erupts, voices are raised, and translators struggle. Cabernet! yells one side, Malbec! the other.

My father smiles at the memory (it was an interesting dinner). ‘We learned tremendously from Atilio’s work and experiments. But I think the most important consequence of this sudden infatuation, by an esteemed Italian winemaker with our grape, was that it convinced me to pursue Malbec.’ It was 1995, and we had a lot to learn.

Building an Archive

As we set out to make top quality wines with an ancient, largely forgotten varietal, the need for rigorous, controlled studies became evident. Enter Laura Catena. Under her direction, the winery embarked on a long-term path of committed scientific research steered through the Catena Institute of Wine (CIW). It began with a selection of 135 cuttings from the Angélica vineyard. Individual plants with valuable characteristics – balanced, low yielding, with small, concentrated berries – were isolated and reproduced as a massal and clonal selection in our high-altitude vineyards, ensuring the continuation of our mother population. Angélica has offspring.

The cuttings were planted first at Agrelo, four clones per row, where climate and soil are comparable to Angélica, allowing for the study of its viticultural and enological behaviour. Next, both the massal selection and individual clones were planted at Nicasia and Adrianna vineyards, in Altamira and Gualtallary, to examine the effect of high-altitude terroir on plant behaviour. In 1997, five of these clones were sent to the University of Adelaide and UC Davis to be studied for viruses. The results were rare and unforeseen; on both occasions, all five were found to be virus-free. The CIW has also shared this genetic material with the wider Argentine wine community. During a zoom session for Malbec World Day 2021, Thibault Delmotte, head winemaker at Colome winery in Salta, declared some of their best Malbec came from Catena’s clones.

For twenty-five years, the Catena cuttings have been studied ceaselessly: their yields, cluster size, shape and flavours (some spicier, some more floral or tannic). Every harvest, their behaviour is observed and recorded. All of this requires patience and commitment – a cutting takes three years to give its first harvest. It demands the kind of energy, determination, and sheer grit my sister (superhero that she is), brings to her every undertaking. It requires teamwork. As I sat down to write this entry, a chorus of voices sent files, figures, findings, followed in interviews by theories, anecdotes, and observations more emotional than I expected. Angélica has students.

The CIW maintains the largest collection of Malbec plants in the world. The list of its achievements and ambitions is long. It includes the most extensive Malbec study to date, and ground-breaking work on terroir. For Alejandro Vigil, head winemaker at Catena Zapata, the impact of climate change is a daily reality. ‘In the context of changing environmental conditions, it’s very much about preservation: the massal selection from Angélica is our great library, a genetic ark and archive of Malbec.’ Today, the focus at the CIW is on sustainability. Ongoing collaborative studies are aimed at the preservation of biodiversity and soil microbiome, understanding, for example, how we might coexist with traditional plagues in a pesticide-free environment.

In our conversations, however, the team seems proudest of its most recent undertaking: the preservation of a century old vineyard, named Rosas after its owner, reproducing its population through massal selection at a different site before it was sold and cleared for housing. Another story.

The Urge to Preserve

Old vines have their quirks and complications. They resist mechanization – everything must be done by hand. They require a particular kind of care. At Angélica, although we’re still flood irrigating, watering has been improved by retouching soil levels, minimizing water loss across the property. We switched from low to high trellis systems, facilitating leaf growth to increase photosynthesis, nurturing a balanced ripening, the development of tannins and aromas. Old vines are less productive. Where a normally producing vineyard might give between 8 and 12 tonnes per hectare, Angélica yields a mere two to three. They can also be healthier, more resilient, staunchly independent.

One of the main reasons for keeping old vines is their genetic material. In any population of vines, the individuals that compose it will be genetically diverse. Some will adapt better to colder, others to warmer climates; some will develop stronger, deeper roots, more resistant to drought; others will present shallow roots, adapting to clay soils and more plentiful water. Maintaining a diverse population (as opposed to a single or small number of clones), offers more consistency in the face of climatic variables. ‘We don’t really know,’ says Laura, ‘how this genetic material might one day help us respond to climate change and disease. But I think it’s clear to all of us at the CIW, that we need to do our best to preserve it.’

Beyond their value as hardy, genetically diverse populations, age alone seems to warrant their conservation: these vines are part of the world’s viticultural heritage. No less their flavours – a century in the making and impossible to recreate. But the strongest draw is also emotional. For Laura, these vines are like people: old and wise, coolly enjoying life. They should be left to complete their life cycle. ‘Their yields are low, and they are only kept alive by flood irrigation, a wasteful form of watering. From a sustainability standpoint, they should be replaced.’ Asked if she ever considered it, Laura laughs. ‘No. We still have a lot to learn from them.’

The Social lives of Vines

The vines at Angélica are marvellously diverse. Some plants are very low yielding, others high. As a population, they’re also remarkably adaptative. They work together, talk to each other. Individual plants that might ripen two weeks apart if planted separately, ripen at the same time. Maybe this is why they’re so resilient. ‘A population of vines,’ Laura explains, ‘socializes through hormones secreted by their roots; they warn each other of impending insect danger. They nurture microbial populations, their symbiotic partners, in order to withstand drought and absorb scarce nutrients.’ They’re amazing. Today, they face higher temperatures and decreasing water supplies. Their efforts are wise, ever more necessary. Angélica remains our constant teacher.

1Dorothy Gaiter and John Brecher, ‘The Dow Jones Argentine Malbec Index,’ The Wall Street Journal, 1999

The photos are provided by Adrianna Catena.