Maher Harb, winemaker of Sept, the only biodynamic winery in Lebanon, tinkers and toils in a single-room concrete winery that sits on layered terraces. He uses an old wood basket press for crushing both his white and red grapes. Although he says this isn’t very efficient, trying to work around the inconvenience of it resulted in happy accidents like skin-contact monovarietals of Lebanese white natives, Obeideh and Merwah. Harb, who grew up in the winery’s small village of Nehla in the northern Batroun district, is constantly throwing the dice when it comes to small batches of juice. “I’ll always be ready to experiment with a Lebanese grape variety,” he says, “whatever the risk is, I don’t care.”

Merwah was always on the tongue of locals in Nehla.

Harb’s earliest memory with his father and grandfather is a 1986 harvest of the village’s old patch of vines. He was 4 years old. “My grandmother used to tell me that the entire village lived from these vines. They would sell the grapes in Tripoli and Douma, and sometimes to the Bekaa Valley,” he says.

Having launched Sept in 2016, Harb is relatively new to the winemaking world. When he was still learning the ropes in France’s Montpellier two years prior, he visited Domaine Vassal, a research center that focuses on ampelography and autochthonous grape varieties, or as Harb puts it: “a central bank of all the indigenous grapes in the world.” He had heard that students there had planted and studied a collection of Lebanese grapes but he was surprised to find that all conclusions deemed the grapes unworthy for vinification. When Harb began experimenting with winemaking on his own however, he couldn’t understand why these grapes were so quickly dismissed.

But through experience, he learned.

Lebanon’s landscape includes two parallel mountain ranges that hug the Bekaa Valley on either side. At a latitude of around 33 degrees, the tiny country’s humid heat is offset by the mountains’ high altitudes. “In Lebanon,” says Harb, “few of the vines can thrive and make good wine under 500 meters above sea level. We’re different because the coastal part is semi-tropical. That’s not the case in Greece or Turkey because we’re on the heel of the Mediterranean Sea. That’s why it’s easy for us to grow mangoes, bananas, and ashta (cherimoyas) near the coast but as soon as you go 500 meters higher, the climate shifts to mediterranean.”

At the time of Harb’s visit, ungrafted vines studied at Domaine Vassal were planted in a neutral environment near the seashore to reduce the threat of phylloxera as the insect cannot thrive in sandy soils. When it comes to Lebanese grapes though, that environment doesn’t work. “I realized the students were doing studies in a reality that didn’t match the conditions where these grapes usually grow,” Harb says.

“In this kind of terroir next to the sea, Merwah won’t thrive, Obeideh won’t thrive, Meksassi won’t thrive. Obviously, it will never get to a normal maturity so their studies were biased and when I understood that, it gave me hope,” he continues.

In 2015, while in the process of creating his first batch of wines with a focus on native grapes, Harb was in search of a source of the ever-elusive Merwah grapes. “As easy as it was to find Obeideh, it was just as hard to find Merwah. Obeideh is indigenous to the Bekaa where agriculture continued throughout different periods in Lebanon’s history. Merwah is indigenous to the Lebanon Mountains though, mostly in Batroun,” he explains. Lands there, especially during the civil war of the 1970s, were neglected as the residents focused on survival, migrating to the capital and disconnecting from the land.

After asking around in Nehla about why the vines of his childhood had gone missing, Harb was told repeatedly that they “got sick.” His theory is a wave of phylloxera hit and locals uprooted afflicted Merwah vines near their homes to shift to higher-yield table grapes which was good enough to make arak, a high-proof anise-flavored spirit that many villagers still make in copper stills at home.

But healthy, forgotten Merwah vines that were wrapping their tendrils around olive, fig, and oak trees were still trudging along; they just needed to be found.

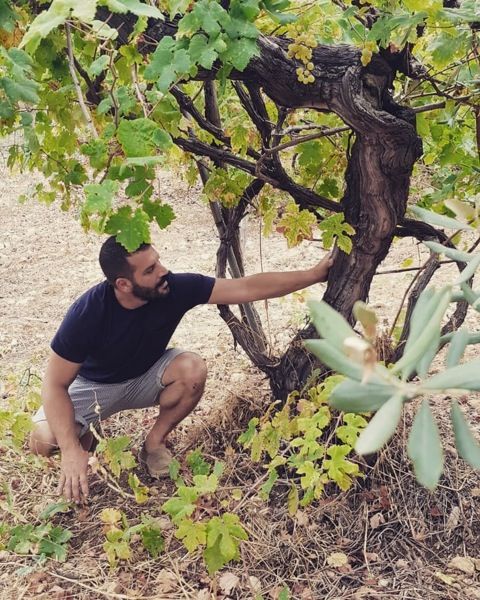

“The first vine I found was hidden under thorny weeds. It was still alive. You can estimate the age of a vine from the width of its trunk while taking into consideration its height or length. The more it's cut, the thicker its trunk will be. This is something our elders know more about,” explains Harb.

There are no concrete scientific analyses done here. Corroborated by testimonies of elders who witnessed a vine’s growth, estimates of a vine’s age are done through the life it shared with others who depended on it. Harb turned to his teta, or grandmother, and asked who planted this first vine he found in the family olive grove. “She said it was my great-grandfather and then she went through the whole lineage of how the land was divided and planted and who did what,” he says.

Once a vine fits into a family tree, it’s then a matter of math. “My great-grandfather was born in 1911 so, along with the trunk’s girth, we estimate it’s between 90 and 110 years old,” says Harb, “but that vine alone wasn’t enough to make wine so I continued my quest.”

Harb asked around in the village to find out who also had some bygone Merwah vines. He was told to go see a man about a vine who lived nearby. “A 90-year-old man is telling me that his grandparents planted these vines and each trunk is 2-3 times as wide as my hand. It’s really magical,” says Harb. Other elders of the village confirmed that these vines were planted by their grandparents. Harb says they claimed that “the sickness didn’t reach these vines” which meant that not only were they Merwah, but they were also ungrafted Merwah.

Like an overprotective parent, Harb worries about giving away too many details about the whereabouts of his hidden vines. He’s named his vineyard “the secret garden” because it’s not the standard series of trellised rows. It’s a noncontiguous collection of scattered vines across three neighboring villages (Assia, Bchaaleh, Douma) that Harb nurtures with the permission of the land owners. “It’s not just about quantity, this is just where they are,” he says.

He explains that Merwah was on the verge of extinction but now it is being revived where and how it has always grown. “This was the old way of planting vines,” he says, ”today’s big vineyards are robotics in nature –that’s not the real thing. Vitis vinifera is a rampant plant. Her existence is based on her capacity to attach to soil or a tree but on the soil, the grapes will rot. On a tree they will take their space.”

When asked whether he felt that these vines produced better wines, he was convinced there’s at least a difference between them. “If it’s done in the correct way, which in my opinion is natural vinification, then yes,” he says, “if it’s done technically, you lose everything. You lose all the nuance that old vines or a terroir can give you. I believe in that.” He went on to explain that old vine wines are not necessarily better but the depth they capture makes him confident about the future of his younger ones. Harb’s ten-year-old Syrah vines which are bottled as the crowd-pleasing Syrah de Nehla make him feel that they, and the wine they produce, will only improve with age. “I say to myself, imagine what this will give in 50 years? Something even more beautiful,” he says.

He also knows that the history behind the vines also makes it a full-package as a product for the international market which is of utmost importance for the longevity of the Lebanese wine industry right now. As the national currency tanks and basic necessities like fuel and medicine run out, exporting the flavor of the country is the most important way to sustain its continued development.

When it comes to knowing if he’s getting these flavors right, Harb says, “I believe doing them, at the beginning, like I do my natural wine, is a very honest way to show us what they are supposed to taste like. Taking them the extra step with skin-contact is an ancestral method to show how our ancestors used to drink those wines when they did it.” For the global palate, French varieties have a thoroughly documented library of expressions and somewhat expected flavor profiles. The lesser-known indigenous grapes of Lebanon are a blank slate for new drinkers but also for the professionals evaluating them. Even for winemakers indigenous to Lebanon, crafting these concoctions is new territory that has only been explored for the last decade or so.

With all the crises Lebanon is facing at the moment, if its winemakers want their bottles to stand out in this great big world, it shouldn’t be about getting it “right” according to everyone else. Perhaps, it should just be about getting it to be what it is: Lebanese.

The photos are provided by Farrah Berrou.