WWC21 – Karkın Vineyards, Turkey

Architect Umay Çeviker has written several articles for JancisRobinson.com and is a fount of knowledge when it comes to Turkish wine, past and present. So it's no surprise that his entry to the old-vines writing competition is about a vineyard in Central Anatolia. His email began with the words, 'I have wanted to write this story for a long time. Many thanks for the opportunity. Greetings from the magical Cappadocia.' See our WWC21 guide for more old-vine competition entries.

Part I

Lausanne – 30 January 1923

Long negotiations between the new Turkish and Greek governments, in the aftermath of the Greco-Turkish war of 1919-1922, resulted in Article One of the Lausanne Convention: ‘There shall take place a compulsory exchange of Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion established in Turkish territory, and of Greek nationals of the Moslem religion established in Greek territory to begin on 1 May 1923. These persons shall not return to live in Turkey or Greece respectively without the authorisation of both governments’.

Karkın Vineyards, Cappadocia in Central Anatolia – May 1923

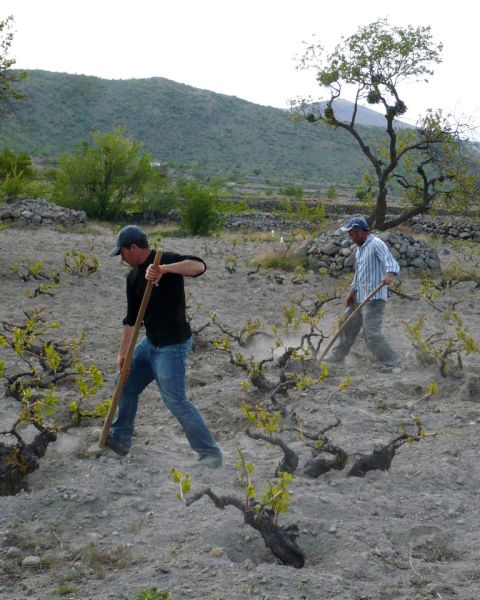

Despite the nerve-racking months of waiting, members of the Mayoglu family, a well-to-do Greek family living in Gelveri, were busy working in their vineyards at Karkın. With the snow cap on top of the volcano still visible, it would have been the right time to fill the pits around the old ‘Keten Gömlek’ vines with soil again. These vineyards at an elevation of 1,250m are situated on the windy northern slopes of Mount Hasan. Thanks to the sandy tuff nature of the volcanic soil the vineyards had been spared the earlier devastation of European vineyards from phylloxera. Locals believed a traditional farming practice they called ‘opening the eye’ also helped preserve the vines.

‘Opening the eye’ involves digging a trench around the trunk, to a depth of 30 cm, to expose the newly formed roots towards the end of February, when the soil is most humid. After six weeks, when the young roots that spread near the surface dry out and fall off by themselves, the vine continues to feed only on its main roots, which in turn are encouraged to reach deeper.

With annual rainfall of less than 350 mm a year this part of Cappadocia faces hot and dry summers, but in winter the temperature plummets to as low as -20 degrees with heavy snow covering the vineyards. Spring frost is a major hazard and can hit until the beginning of May. When the risk is gone, the vines are pruned and the open pits are filled back with soil. In the vineyards without a surrounding dry stone wall, additional soil is sometimes piled over the trunk to protect the vine from the harsh winds.

Provided a good growing season had followed, this was all the Mayoglu family had to do for a healthy harvest. In the year of 1923, they were not sure if they could make it until then.

İstanbul – 1920s

As skilled goldsmiths, the three sons of the Mayoglu family lived in Istanbul. As a side business they also traded the wine the family produced in Cappadocia. Under the Ottoman policy of toleration to enhance peace and stability non-Muslim subjects had been allowed to produce and consume wine. In the early 20th century, the ports of Thrace and the Aegean regions were busy exporting wine to Europe in quantities even larger than Turkey’s total production of wine today, so the lucrative tax revenues were hard to ignore too.

Having witnessed the First World War and the subsequent war between Turkey and Greece, the last decade had been tough for the minorities of both sides. Since the 1912 Balkan Wars when the ethnic Turks living around northern Greece had been forced to flee to Anatolia, minorities were threatened by the prevalent tendency in the early 20th century towards the breakup of multi national empires to create nation states. The Ottoman government’s settlement of that community in villages close to the ethnic Greeks hinted at things to come.

Gelveri, Cappadocia – May 1923

Even though the magical town of Gelveri, known for its stone mansions and rock-cut monastries, had never been a battle zone, life was getting harder for ethnic Greeks as tension grew between both communities. Although they had been living in this part of Central Anatolia since antiquity, in the end they were forced to leave their homeland and emigrate to Greece. It was so hard to believe that they kept curing their meat, harvested the grapes to make their wine and molasses. Hoping to return soon, some laid the walnuts they picked on the ground to dry, just before they left. They did not know at the time that it would take three generations before they returned to see their homelands ever again.

The Mayoglu family and other people from Gelveri were settled near Kavala in north-east Greece in what they would later call ‘Nea Kalvari’ after their hometown. Because they knew that the town’s name in Turkey would soon be lost, just like their local dialect.

Meanwhile, Turkey lost an entire middle class almost overnight: its merchants, artisans and winemakers, along with centuries of collected knowledge and traditions.

Part 2

Güzelyurt – 1995

Udo Hirsch, a German national who was then a consultant working in the Caucasus, first came to Güzelyurt in the mid-1990s to conduct a workshop on handicrafts. Gelveri, the town’s original Greek name, had ironically been changed to ‘Güzelyurt’ that translates as ‘beautiful homeland’ in Turkish. Hirsch recalls being offered bread fresh from the stone oven of a beautiful ‘Rum’ house. (Turks name the people of Greek origin that they lived side by side for a millenia as ‘Rum’ and use the word ‘Greek’ for the people from the mainland.) “In each neighbourhood a couple of houses share the same oven to bake bread. The taste of it served with homemade goat cheese blew my mind” says the tall, silver haired man now in his seventies: “I decided to come back soon”.

He returned a few years later and bought the same house where the Mayoglu family had lived.

Udo (pictured at the top of this article in his cellar at the winery) is not the type to desire a peaceful retirement after his fifty year long professional career as a consultant for the sustainable use of natural resources. Inspired by the experiences he gained in Georgia, where he lived for the good part of his career, he decided to establish a winemaking business to support local grape growers, after careful study of the history and nature of this region. He founded a winery with his partner, ceramic artist Hacer Özkaya, and they travelled all over Turkey to collect old amphorae used in winemaking. For the grapes though, they wouldn’t have to go far.

Karkın Vineyards – 2010 onwards

Although the Turkish immigrants who replaced the Greek population in the 1920s were not interested in making wine, they did not remove the vineyards. Locally known as ‘fruit gardens’ the vineyards are field blends of indigenous whites Keten Gömlek, Hasandede and Bulut along with red grapes Dimrit and Kalecik Karası. Some of these varieties are grown for molasses, some for drying and some for eating. Most gardens had a treading vat for stomping grapes and a stone fire pit for cooking molasses . Thanks to this local architecture reflecting the economic opportunity of the grapes, the vineyards survived even after the population exchange.

Some vines at the Karkın vineyards are over 100 years old, but the average age of the vineyards is kept between 50 to 60 years. One reason for this is the widespread belief that older vines yield less, and the other is that it is fairly easy to replant in a phylloxera-free vineyard. Since the sandy tuff soil is dry to a depth of 60cm in April, all it takes is to bury a 70-80 cm long cutting that carries an old piece of rootstock.

The other propagation method used is layering. A shoot is allowed to grow long enough to reach a desired point in the vineyard when a stone is placed to weigh down the the branch. When it develops its own root system after a year it is seperated from the parent plant.

Harvesting requires many passes through these fruit gardens to pick the ripened grapes. The rest is left to the archaic methods of winemaking at the Gelveri Manufaktur winery where low intervention principles are pursued.

Güzelyurt – Summer of 2015

As Udo was preparing to leave for the vineyards one August day, a bus with a Greek license plate parked a few meters from his house. It was carrying the third and fourth generation descendants of the Greek immigrants who were travelling as part of an annual mutual visiting programme. It’s heart-breaking to watch them repeat the futile efforts of family after family trying to identify the traces of memories passed down from their ancestors. In the evenings, the two communities sing and dance together to the many songs they share.

Witnessing this journey gave Udo the idea of making a wine in memory of the Greek people who lived in Gelveri and who looked after the vineyards for many centuries. Keten Gömlek, the old variety of the region would be the ideal choice. Translated as ‘linen shirt’ due to its thin skins, it makes perfumed wines with good acidity. This early ripening, small berried grape has a surprisingly loose bunch and resists vine diseases well, especially mildew.

Udo ferments Keten Gömlek, with a 30% addition of red grapes harvested at the same time, in amphoras locally known as ‘küp’. After the fermentation with wild yeasts is complete, fresh terebint berries are added and the wine is left to age for two years in the amphora. The berries of the terebinth tree are known for their resinous smell and medicinal properties. Udo used them to flavour the wine and preserve it as a nod to the Greek heritage of the area. He has been releasing this wine branded as ‘Mayoglu Terebinth’ since 2015 keeping the Keten Gömlek as its backbone and changing the red variety each vintage.

When they left their homeland the Mayoglu family were among the 1,5 million Greek settlers and 500,000 Turks who were forced to migrate. As they tried to embrace their new lives they faced being ‘twice a stranger’(*): among their nationals who were unwilling to acknowledge their existence for many years, and again in the lands they had left where their traces were being erased over time.

But the Karkın vineyards prove the opposite. They have survived and local communities have maintained centuries-old viticulture techniques, autumn festivals and ancient grape varieties. Just like the mutual songs and dances. And the architecture. And the many common dishes that Greeks and Turks enjoy having a squabble about. And the names of Mediterranean fish which we share. Politics cannot reach such deep roots.

When Udo made a return visit to Nea Karvali in 2017, he took a bottle of Mayoglu Terebinth with him and shared it with the people who, after four generations, still call Anatolia their homeland.

All I can do is to dedicate this article to those whose stories were never told.

For further reading

- ‘Aivali: A Story of Greeks and Turks in 1922’ by Soloup (2019)

- ‘Farewell Anatolia’ by Dido Sotiriou (1962)

- ‘Twice a Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey’ by Bruce Clark (2006) (*)

For further watching

- ‘The Great Population Exchange between Turkey and Greece” by Işıl Öcal: The Great Population Exchange Between Turkey and Greece

- ‘Twice a Stranger’ directed by Andreas Apostolidis & Yuri Averof: Twice A Stranger

All photos apart from 7, 8 and 15 are from the Gelveri Manufaktur archive. Photo 8 is by Sabiha Apaydın. Photos 7 and 15 are from Umay Çeviker's own archive.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,397 featured articles

- 274,704 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,397 featured articles

- 274,704 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes