The Heart of a Vineyard: Scherrer Family Old Vines

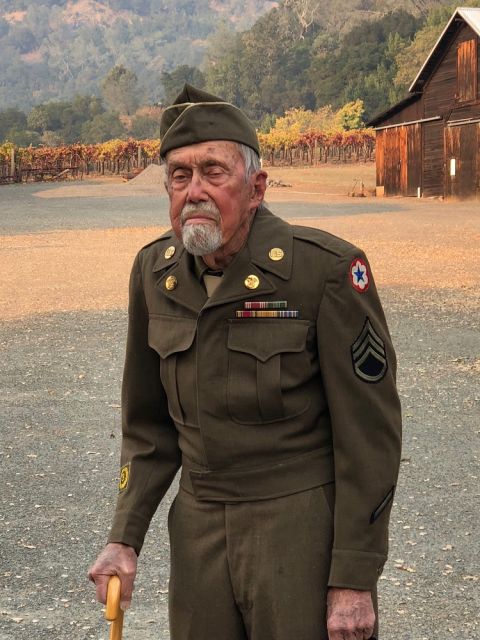

It was a cool November night in Alexander Valley, and Fred Scherrer was sitting at his father Edwin’s bedside manning the morphine nepenthe. In the early hours of the next morning, 93-year-old Ed, holding his wife’s hand, would slip away from this life.

Outside the window, the family vines were bursting with brilliant red and yellow leaves. Their brittle texture would make them nearly disintegrate in your hand, but from afar, they looked as alive as they would appear all year. They would soon retire to dormancy until their first buds would peer out the following spring.

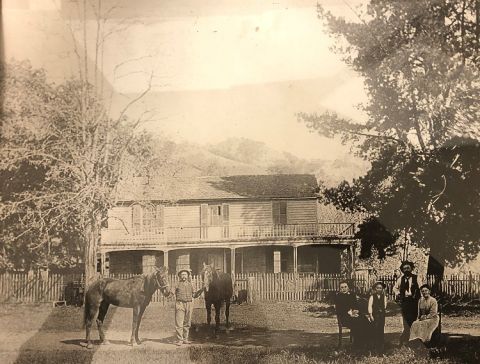

The land was originally purchased by Ed’s grandparents, Fred’s great-grandparents in 1889. In those days, prunes were the primary crop. In 1912, it was Ed’s father, Frederick, who spearheaded planting vines – Zinfandel and Alicante Bouschet predominately; the Alicante fetched the higher price on the market at the time. By virtue of instinct, or else good fortune, Frederick opted to graft to St. George rootstock, making the vines resistant to Phylloxera. Perhaps this is why some of those original vines still produce beautiful fruit today. When viticulturists with fancy degrees came along and recommended AXR1, Ed was ardent in his defense of St. George. He may not have been part of academia, but he had seen the proof in the pudding.

When Fred came along, he didn’t have much leisure time with his father and grandfather. Rather, his bonding with the family patriarchs came in the form of work. Being lanky for his age, when Fred turned 8, his feet reached the pedals of the family truck, so he manned the vehicle while his father and grandfather placed and removed the wooden props for the prune trees at the beginning and end of each season. When shoot-thinning needed to be done, Fred recalls his boots becoming soaked with sweat from the endless hours in the vineyard. Ed had grown up during the depression and had then enlisted in the military, and work ethic meant survival.

Fred had done his best to rebel against his father’s hard-nosed, conservative way of life. He was determined to be a veterinarian until his teenage years, when he began experimenting with making wine in the backyard. Until then, the grapes from the family vineyard had been sold. Fred then enrolled in fermentation sciences at UC Davis. Even if he was going to engage in the family business, he was going to do it his own way. He grew out his hair, played guitar, and started dating a Berkeley girl, much to his father’s dismay (and admonishment at times.) That Berkeley girl became Fred’s wife Judi, a remarkable business mind, and now his partner at Scherrer winery.

I met Fred on my very first visit to the North Coast. His was the first true winery in which I set foot. At the time, I recall a vague tinge of disappointment. I was an idealistic young sommelier, and I had imagined all wineries must look like those you see on Napa postcards. I’ve ironically now grown a bit of disdain for these sorts of operations because their expensive hallowed halls seem to be so often devoid of heart. Fred’s winery was a no frills former apple-packing warehouse, but I would soon learn that it was bursting with heart.

While I’ve now known Fred for years, It wasn’t until this past fall, just before Ed’s departure, that I finally saw the Scherrer family vineyard for the first time. I had become stranded on the West Coast after my harvest was cancelled as a result of wildfires. I found safe-haven with Fred, as his unofficial intern. We drove from his Sebastopol winery up to Alexander Valley in his 1997 F-150 truck, while we both wore N95 masks, which now doubled as protection from both a global pandemic and smoke.

Perched along the hillside was the family home, built in 1853, long before vines had ever thrived in these parts. A maze of vines sloped toward the South, drinking up the sunlight at its afternoon height.

Fred and I began to walk, our boots kicking up bits of dry, powdery earth along the way. He knows every vine by heart, when it was replanted, what it yields. The oldest vines, dating back to 1912, are spur-pruned and, remarkably, dry-farmed. They’ve been trained by 3 generations to thrive on struggle.

After our walk, we strolled up to his parents’ home, looking out over the vineyard. An abundant fruit and vegetable garden sat out back, and 2 cats roamed around. His mother was seated at the kitchen table, and not surprisingly his father was up and about. His sister Louise, who is now integral in farming the land, had just departed for the day. Neither Fred nor I knew at the time that Ed wouldn’t be with us much longer. There was no way to know, as Ed never slowed down. He was on the tractor less than one week before that last November night.

At Fred’s harvest party a few weeks later, he busted out his guitar, and so commenced an hours long jam session. This moment displayed just how different he is from his father Ed. However, for every moment like this, there are twenty when he has his head down and is working sans cesse. While Fred had done his best to enjoy the respite provided by less fruit to harvest, as a result of the year’s fires, you could tell he was squirming a bit inside. Just like those vines, he had learned to thrive from hard work. This is a man who has fashioned a make-shift shower in his winery, so he doesn’t have to go home for anything during harvest, after all. While he may text me song lyrics that he’s working on, he’s usually come up with them while doing punch downs or analyzing sugar content. He may be part hippie, but Fred is also, through and through, his father’s son.

When you taste Scherrer “Old Vines” Zinfandel, the wine possesses remarkable structure. For a variety that is often jammy, even bordering on blousy, and heavily-oaked, this Zinfandel is remarkably focused. Its acidity is, dare I say, racy, and its herbal quality and restrained blue fruit make you realize just how stunning and thought-provoking this variety can actually be. Each vintage reflects the specific character of the particular growing cycle, but the through lines are unmistakable. As wine professionals, we often have debates about the true meaning of terroir, and while I cannot suggest an ultimate singular answer, I must admit this wine tastes like only a wine made by this man from these vines could.

As for the future of the Scherrer Family Vineyard and Scherrer Winery, the script has yet to be written. Fred and Judi’s children Rachel and Ryan are in the exploratory years of their 20s. However, they’ve both spent time learning the ropes, and Rachel does seem to have that unique combination of clear, analytical thinking coupled with a deeply artistic spirit that makes a truly great winemaker. She takes after her father.

The photos are provided by Jillian Riley.