WWC22 – Daniel Mills

In an interesting twist, this submission to our 2022 writing competition explores the regeneration of cider production in the heart of California's wine country. See our WWC22 guide for even more great wine writing.

Daniel Mills writes I am a wine professional and freelance writer in Phoenix, AZ, where I currently manage and buy for Montecito Bottle Shop, part of Restaurant Progress’ hospitality group. I also work as a wine rep for Good Omens, a Phoenix-based importer and distributer of biodynamic, honest wines. I spend much of my time reading, writing, and being outdoors, trying to better understand the land and history.

Bardos Cider and the Doctrine of Discovery

Upon Seeing the Great Apple Trees

This past March, I embarked on a backpacking trip into Arizona’s Superstition Mountains in search of an old apple orchard. Located to the east of Phoenix’s sprawling metropolis, it is a rugged and largely inhospitable mountain range where extreme summer temperatures, torrential monsoon rains, and winter snowfall leave short windows of accessibility to the more remote regions. My father and I have made an annual tradition of these trips, backpacking deep into wilderness areas to forgo the comforts of civilization and remember what it’s like to sleep underneath the stars.

Our specific destination, Reavis Ranch, is a tiny historic ranch located in the higher elevation portions of the Superstitions. We reached the trailhead after driving nearly twenty miles on choppy dirt roads that intersect with a system of arroyos, or dry creek washes carved out from seasonal monsoons that are notorious for danger. Even a light rain can turn an arroyo into a hotbed for flash floods, stranding vehicles on either side until the gulch is safe to pass through.

We began hiking among chaparral scrub and cacti, and a couple hours later arrived at our campsite around 1,700 meters among pine trees where Spring had barely just arrived and snow patches stubbornly checkered the ground.

Reavis Ranch, like the Superstition Mountains in general, is a subject of great lore. Elisha Reavis, nicknamed “The Hermit of the Superstitions”, founded the ranch in the 1870s in Apache Territory after trying his hand as a gold prospector in the California Gold Rush of the mid 19th century. He planted an impressive array of crops, including apples, which he would then sell in nearby mining towns by loading mules or horses with the harvest, trekking the rough terrain each way. While his life is the subject of much speculation, it’s not difficult to imagine that Reavis was of a peculiar disposition. What drives a man to settle so far removed from his peers, condemned to hard labor as a means of survival, and exposed to the hostilities of Apaches in their home territory?

Standing on the ranch, I took account of my surroundings. Massive pecan trees still in hibernation towered on the edge of hay fields turned golden by the afternoon sun. Grape vines, possibly the native Vitis arizonica, crawled along a foundation where remnants of a hearth could be discerned. A perennial stream nearby revealed the fresh tracks of white-tailed deer in the snow piles that lined its banks.

And then there were the apple orchards.

I stumbled right upon them at first, mistaking them for a large and impenetrable bramble patch before stepping back and realizing what was in front of me. The trees were large, sprawling, and otherworldly—their limbs branching horizontally outward, shaped by the burden of their own immense weight. It was difficult to see where one tree ended and another began. A century of isolation had turned them into a mangled network of entwined growth, both eerie and beautiful at the same time. The first signs of bud growth were barely visible in the early days of March.

Not long after, I’d learn more about the great apple orchards that persist across the United States.

A Rebellion in Wine Country

Aaron Brown and Colin Blackshear both have roots in Sonoma, but they were not entrenched in the wine industry there. Instead of the idyllic, romantic landscape of rolling vineyards many envision the California wine region to be, Brown explains that he and his friends saw the corporate, Disneyland-esque nature of the industry as something to be resisted.

“In the [1990s] when I grew up, the wine industry took this crazy turn and became a huge tourist industry and like a cash grab, so when we were growing up, all my friends hated wine,” he explains.

Later on, during his time in England, Brown was introduced to more holistic, environmentally conscious forms of agriculture through cider production, which placed emphasis on utilizing well-established orchards that date back to the Victorian era. After seeing how highly regarded and sought-after those historic orchards are, Brown gained a greater appreciation for the derelict, forgotten orchards that exist throughout much of the U.S., and particularly in California.

In 2019, Brown and Blackshear released their first commercial vintage of Bardos Cider.

“When we first started doing this, we were just using fruit that was being left to rot. So, we were getting the fruit for free, working in the community, and helping clean up the orchards,” Brown says, “Making cider felt like a rebellious thing to do in wine country”.

Not only was the fruit sourced without formal contracts, but Brown would drive to Mexico and fill his Toyota Forerunner with glass bottles from recycling facilities that he would then bring home and sterilize for bottling, creating a product from materials where hardly any money was exchanged in order to build it. Today, only a few years later, Bardos Cider’s production has increased to several hundred barrels a year and is distributed throughout the U.S.

While cider’s popularity in the U.S. is growing, it is still confronted with a lack of consumer awareness and persistent misconceptions, such as that it is always sweet or that it lacks the nuance and complexity of other fermented beverages like wine or beer. Of course, cider has a long and storied history in places like England, Normandy, and Basque, where it is heralded as a pillar of the cultures and identities of these regions. The lack of awareness and respect for cider in the states is not entirely accidental, and is due at least in part to bureaucratic restrictions placed on labeling by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), which approves and oversees compliance with federal laws related to alcohol.

Specific site names, varietals, vintages, and other identifying information that is commonplace and in many instances required for wine is far more restrictive for cider, if not outright prevented entirely. Such identifiers on labels could dramatically improve consumers’ confidence in purchasing styles or sweetness levels they prefer as it does with wine or beer. TTB regulations for cider have long been a topic of contention, leading to mildly humorous scenarios where lawmakers and regulators are unsure of whether to classify the beverage as “Champagne” or “beer” for tax purposes.1

Rather than be deterred by these barriers, Bardos has embraced them as part of a narrative of outcasts grinding against the status quo, proclaiming on their website that, “As witches, hermeticists, esotericists and magicians of the past were forced by the institutions of church and state to communicate in code, present-day US cider makers are restricted from participating in the winemaking community.”

In order to circumnavigate restrictions on labeling, they have created a series of symbols printed on their back labels, which can then be cross-referenced with a key on their website to learn specific varietals and production methods for each style. One symbol correlates to “two weeks on skins”, referring to how long the juice was macerated for, and another signifies “100 year old Gravenstein”.

Their statement continues, “Having grown up in the wine country, we are fine with this division because the wine industry has devastated the natural environment of California. Overseas money has industrialized the landscape of California and corporate interests have made it next-to-impossible for family wineries to carry on producing real wine.”

In conversation, Brown is far more forgiving and diplomatic in this assessment, expressing that, “As with anything, I would say that 99% of the time people start out with good intentions, but then as things become more institutionalized, problems arise.”

The issues he raises, while multi-faceted and complex, have tangible, real world consequences. Much of Bardos’ ethos and production methods are a conscious attempt at countering the environmental degradation and influence of multinational conglomerates that continue to change the landscape.

On Stewardship, Not Farming

Across the United States, an untold number of apple orchards exist whose origins can be traced back to the earliest days of European inhabitance. With the exception of a small number of native species belonging to the Malus genius, colloquially known as “crab apples”, the domesticated apples we enjoy today are not native to the North American continent. Encountering these native Malus crab apples in the wild is not guaranteed, either, since over time they have hybridized with domesticated and ornamental species.

It is estimated that over 15,000 varieties of apples once flourished across North America, but that number has now dropped by eighty percent to around 2,500. Only one hundred varieties are grown commercially, with the single variety Red Delicious accounting for 40% of production. Many of the now disappeared heirloom varieties were grown for cider production, which dramatically decreased during and after Prohibition, and from which it arguably never fully recovered.2

In the Eastern United States, apple trees grow wild with little difficulty, and will differ from their Western counterparts, retaining higher acidity in the fruit due to generally cooler climates. In California and to the West, established orchards are able to survive off seasonal rains, growing hardy and more resistant to unpredictable weather events and drought like deeply rooted old vines.

In order to achieve desired acidity levels in their cider, Bardos experiments with macerations and other production techniques according to varietal, harvest time, and terroir-driven factors. Compared to grapes, apple trees have a much longer harvest window, as early as late summer for some varietals and into December for others. “Winter Walker”, one of Bardos’ offerings, is produced entirely from late ripening varietals harvested in November that are naturally higher in tannin.

Brown and Blackshear maintain orchards in focused, intentional ways without the use of any pesticides, fertilizers, or other chemicals. Many varietals have irregular crop loads, known as “biennial bearing”, which can greatly effect fruit-size and concentration from one vintage to the next. Pruning can help alleviate stress in years where the tree is under strain from too much fruit set.

“With these old orchards, you don’t really farm them, you steward them. The main enemy of these trees is themselves. When the [fruit] set hits, it’s so heavy it will break the branches and kill itself, so you go around propping them and hand cutting off deadwood,” Brown elaborates.

Fermentation is achieved through native yeast, as opposed to inoculating with cultured commercial strains. There is no fining, filtering, or added sulfur dioxide. To create a sparkling cider, the current vintage’s juice is used as a dosage, re-inducing fermentation. The cider is dry, tart, and lively with refreshing acidity. Other producers working in this style are Oyster River Winegrowers from Maine, South Hill Cider from the Finger Lakes, and Coturri, who has been producing in Sonoma since the late 1970s.

Their cider making adheres to the same ethos and philosophy as the natural wine movement, which promotes returning to techniques utilized before the introduction and widespread use of chemicals in the middle of the 20th century.

However, natural wine was not on Brown’s radar when he began.

“Everything I was doing, I discovered my peers in wine making were now also doing. I didn’t know about natural wine or anything. It’s sort of this magical experience since my partners and I joined Bardos. It’s an experience that people are really drawn to,” he explains.

Now, they have found community in like-minded wine makers, experimenting with co-ferments and other collaborations, such as with Wavy Wines of Sonoma, who they produced their “Nouveau” with, a sparkling Petite Syrah and cider co-ferment.

Against the Doctrine of Discovery

For Brown and Blackshear, the experience of working with old orchards provides a unique insight on history and sustainability. Some of these orchards were established during Mexican rule in present-day California, which followed a long period of Spanish colonial rule. “Mestizo”, a Spanish word that refers to a person of mixed European and Native-American descent, is featured prominently on the front of their bottles as a nod to these conflicting, but inseparable histories.

“In California, you have a kind of appreciation for this sort of multivalent perspective. We learn history in school, but now it’s the 21st century, so there’s all kinds of other narratives and perspectives that weren’t represented in mainstream culture. You start digging around and finding evidence of old horticulture activity and thinking more from an Indigenous perspective”, Brown relates.

Tribal sovereignty, water rights, and land management are increasingly pressing issues in the age of climate change and year round wildfire seasons. Sustainable farming techniques like biodynamics and permaculture are becoming more widely embraced, and while they have insights to offer, are lacking in their ability to address the systemic nature of environmental and social problems. Sustainability is a nebulous, complex idea and conversations surrounding it often fail to account for the long, problematic history of land that has been colonized numerous times by various powers over the past 200 years.

Questions regarding land management and best practices that consider this history are far less abstract and more relevant when the source of your fruit, old apple orchards, have survived on land that once belonged to another country, and which now exist in a nation that struggles to comprehend the continued mistreatment of Indigenous peoples, as well as those who exist on the other side of a border wall to the South.

The experience of working with these orchards has been a catalyst for Brown challenging dominant narratives on land management. He laments that wineries have bulldozed historic orchards in order to establish biodynamic or organic vineyards as the region struggles with an oversupply of grapes, devaluing the market and causing some industry leaders to advocate pulling out existing vines.3

On Bardos Cider’s bottles, the phrase, “Resist the Doctrine of Discovery” is placed strategically on the bottom of the back label, and is easy to miss entirely if you’re not looking.

It’s a phrase that encapsulates the frustration with “conquering in the name of organic”, as Brown describes the behavior of wineries that engage in these practices. The pioneering, adventurous spirit that defines American viticulture as a region motivated by experimentation and forward progress, is the same spirit that can perpetuate harm to the land when left unexamined.

Alternatively, cider making allows a contrasting approach, a differing ethos, by honoring and making use of what is already here in the great apple orchards that persist across the United States, whose history belongs to no single country or people alone, but ultimately to all of us through our stewardship and care.

Notes

1 https://vinepair.com/articles/cider-vintage-label/

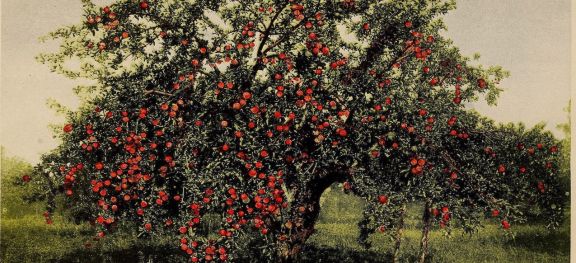

Main image is from Wikipedia Commons. All other images are courtesy of Bardos Cider.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,396 featured articles

- 274,621 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,396 featured articles

- 274,621 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes