Diana Hawkins writes Diana Hawkins is a Certified Sommelier with a Bachelor of Science in Engineering from Harvey Mudd College; a Publishing Arts Certificate from Antioch University; and a Master of Science in Wine Science with First Class Honors from the University of Auckland, where she studied microbial terroir. In 2012, she quit her corporate job to pursue a career in the wine industry and has never looked back. During her time as a sommelier in Chicago, she developed wine and beverage programs for top Chicago restaurants including James Beard award-winning Lula Café and worked the floor at three Michelin star Alinea. In 2017, she traded in her wine key for a pair of work boots and moved to Aotearoa New Zealand to pursue a winemaking career. She is based in Aotearoa New Zealand, where she works as the assistant winemaker for the McBride Sisters and for her own wine brand, Responsible Hedonist. Always hungry for more wine knowledge, she completed her WSET Level 3 Award in Wine with Distinction in 2021 and dreams of becoming a Master of Wine. Diana is a Roots Fund and Women of the Vine and Spirits Trust Scholar and has been featured in SevenFifty Daily, Plate Magazine, Chicagoist, The Chicago Tribune, among others. She has written articles for VinePair, SevenFifty Daily, Wine Enthusiast, and JancisRobinson.com. When not exploring the wine world, Diana loves listening to music, kayaking around Waiheke Island, and practicing yoga.

What is a weed but a flower ‘out of place?’ and other Fukuoka lessons I learned from Tai-Ran Niew

Apocalyptic Dreams

I often lie awake at night contemplating how many microplastics and forever chemicals I ingested during dinner and how we’re ever going to get them out of the food chain. My weekly beach-strolls aren’t complete without recovering remnants of water bottles battered by waves and whatever other detritus of the Anthropocene has washed up that evening. As I walk, I wonder if we’re the last humans to know the taste of real honey or watch fireflies light up summer nights; the last to drink water or eat seafood without fear of contamination (assuming there will be any fish left to eat at all); or the last to enjoy a hot cup of coffee.

Surely, being the last comes with the responsibility to both conserve and savor?

Conserving so future generations can also have these delightful experiences, and savoring so, if all is lost, we can at least report back that once upon a time life was glorious.

…Does anyone else think like this or is it just me?

Maybe it’s because these thoughts run round my head on a regular basis (and I don’t want to live the rest of my adult years in a Mad-Max-inspired, dystopian hellscape), I think it’s way past time we do something to address this impending environmental calamity.

Humanity has reached a point where we need truly radical ideas to solve these challenges because it’s clear the status quo will not get us where we need to go. Perhaps nowhere are new ideas needed as much as in the agricultural sector, which has remained mostly unchanged since the 1960s. Sure, the tech, chemicals, and yields have improved over the decades, but the approach to farming and role of the farmer have mostly remained static.

Regenerative agriculture is often viewed as a way to revitalize soil health and farm sustainably.

But, what if it’s our approach to agriculture that’s actually in need of renewal?

Natural Farming

I'm sure the adoption of fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, etc. after WWII was because they actively made farmers’ lives [and livelihoods] better. So, I don't begrudge people doing this. But now we have computers, different materials, electric engines, and other technology. Yet farming never asked:

‘Do we still need the chemicals? Is there a way of redesigning everything from scratch that would be better for the planet? Maybe even economically?’ – Tai-Ran Niew of Niew Vineyards

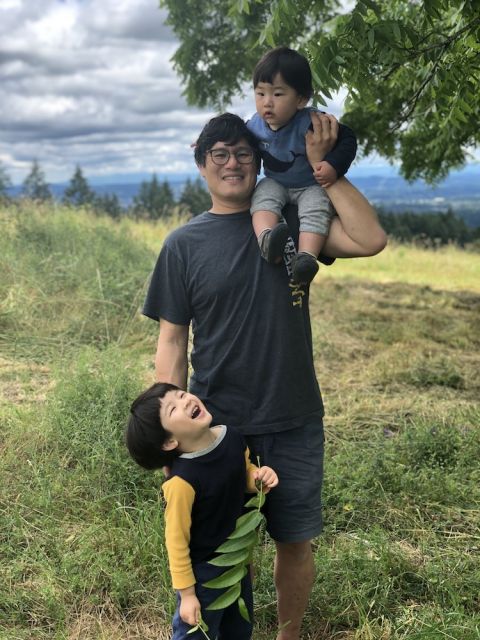

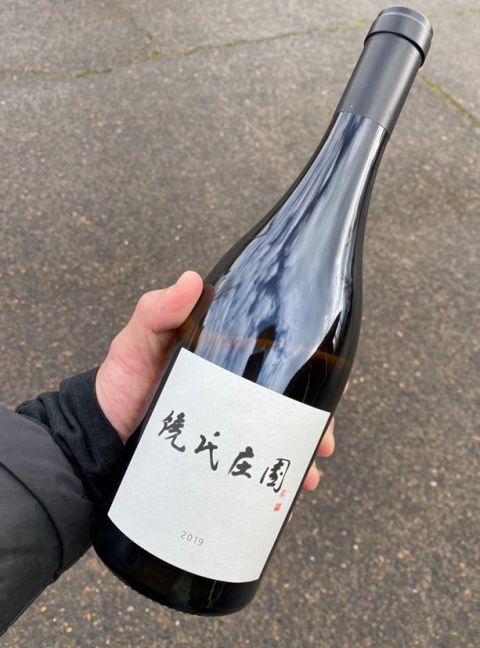

On an east facing slope amongst the Chehelam Mountains in Oregon sits Niew Vineyards. The vineyard is unusual due to its high elevation, Chardonnay plantings, and viticultural approach. It is wild – occasionally so much so that Tai-Ran Niew, its proprietor, will weed whack the interrow to rein in its exuberance. Though aside from the occasionally whack and mow, the vines are left mostly undisturbed. They are trellised, but the canopy is minimally managed. Rain and moisture stored deep within Jory soils are their only source of water. You won’t find a tractor or sprayer here, and neither organic nor chemical sprays are used. Tilling is also out of the question. If powdery mildew threatens the vines, a drone armed with cow’s milk is deployed – the only thing he currently applies.

I learned about Niew Vineyards during a conversation with Yooie Chang of Yoovin Distribution. Before that, I hadn’t heard of Tai-Ran Niew or Masanobu Fukuoka, a Japanese farmer who created the philosophy of natural farming, which now shares his name. Fukuoka is similar to other regenerative practices where soil cultivation, plowing, and tilling are deemed unnecessary, as are herbicides and pesticides. But there are key differences. Weed control, compost, and other soil preparations are not utilized leading to the oft-quoted Fukuoka expression “nature doesn’t compost.”

If you hold space for this adage, as I did, you have to admit that it doesn’t – not really.

“In nature, you don't gather plant material, move it a long distance away, process it, and then put it back on the same spot,” Tai-Ran explains. “The carbon footprint of that is huge, and if you don’t need to do it, why do it? The point of Fukuoka is to only do what is necessary. You can do very little if everything is synchronized properly with what nature wants to do,” he continues.

It is romantic to say: ‘Tai-Ran left the UK and moved to Oregon to start a vineyard.’

And, while factually correct, it ignores the years of research and experiences that led him to do so.

Tai-Ran is first and foremost a pragmatist, which is fitting seeing as he has a PhD in Aeronautical Engineering and spent years working in finance. When he left finance in 2006, he started devouring oenology and viticulture books. Somewhere in between contributing to the Purple Pages and starting Niew Vineyards, his wife gifted him Fukuoka’s The One-Straw Revolution, which changed his views on farming.

“If you leave a rainforest alone, will it get more or less fertile overtime? The answer, of course, is more. Mother Nature has designed an ecosystem that’s supposed to keep going with no human intervention. So, why don't we let nature help us? It’s intrinsically more powerful, intrinsically more sophisticated, and intrinsically better for the environment.”

Wild and Pristine

Rather than fight what nature wants to do or have a knee-jerk reaction to it, Tai-Ran instead observes. This way he can fully understand the natural mechanisms behind what is occurring. He studiously takes notes and critically reflects upon what he sees. Only after careful, meticulous observation does he intervene. This approach is challenging for most grape growers to wrap their minds around, especially those who view themselves not as farmers but as sherpas of the vine.

Producing high quality grapes has traditionally meant exacting as much control over their environment as practical, standardizing vines so they look identical to their neighbors, and supporting them using fertilizer and protective sprays. However, if left in a (mostly) undisturbed state, nature can also ensure a crop is maintained on its own. Wild ecosystems can attest to this as can Tai-Ran, who is already seeing evidence of this within his six-year-old block.

“There is a vine that’s performed better than all the others, and I have no idea why. I go there, look at it, and really enjoy that this vine has worked everything out on its own. It is producing good fruit effortlessly – and that, to me, is unbelievably satisfying. I feel that I am closer to nature because I've removed myself more from the process. I'm literally watching nature say: ‘You know what that spot? It’s perfect.’”

Smith Acres, where Niew Vineyards is located, was a century-old, family-run Douglass Fir forest. It was logged and left undisturbed (save for a few stray cows) for at least a decade until Tai-Ran bought it. By the time the land changed hands, blackberry brambles had completely taken over making the site impenetrable. Blackberries are a common pest in Oregon, and, due to their prickly disposition and ability to rebound, they are difficult to manage. Faced with thickets of thorny brambles and untamed wilderness, many growers* would be inclined to bring out the heavy machinery and utilize herbicides to prepare the land for vines.

Tai-Ran used manpower and a herd of goats.

“The goats don’t dig up blackberry bushes. They just keep nibbling at them and eat until it's clean,” Tai-Ran says. While watching the goats gorge themselves on blackberry bushes, he noticed blackberries grow like mad in August, while the grasses are dormant in the dry heat. By the time spring came around, the blackberries are so far along, that grasses and other vegetation can’t outcompete them. “But if you actually mow or have goats graze in August, you give the grass a chance to catch up in the wet Autumn. Within two years, the grasses win. That's it, you don't need RoundUp. That's a classic example [of what can be learned from] Fukuoka,” he continues.

By observing first, Fukuoka lessons can be recognized and leveraged to the grower’s benefit. This immediately reminded me of a natural method put forth to mitigate virus-carrying mealybugs in Aotearoa New Zealand. Growers anecdotally noticed that organic vineyards didn’t have as much of a problem with mealybugs as those farmed traditionally. Research was carried out to better understand why this may be. It turns out that in monocultural vineyards, the only thing for mealybugs to munch on are grapevines. However, if cover crops or grasses are in the interrow, mealybugs are content to feast on what’s available there and do not always seek out higher vegetation. Diligent observation and connecting empirical data together are the bedrock of scientific discovery and innovation. Without it, progress cannot occur.

Nature's bounty

To truly renew something requires starting over and re-generating it from the ground up.

It means asking questions that were once viewed as answered and creating radically new ways of doing things – this is why a car is not simply a buggy pulled by mechanical horses. Completely revitalizing the concept of farming therefore necessitates a rethink not just of nature and farmer’s roles but also of how we think about cost.

Whether it’s more cost-effective to farm hand-in-hand with nature or through sheer force of human will and technology is an existential question that warrants reflection. Growing grapes and doing so in a financially profitable manner have been tied together so tightly for so long that most cannot tease the two apart.

Yield forecasts, grapevine maturity targets, and re-planting programs often have more to do with economics than grape or wine quality. These metrics are commonly used to weigh the pros and cons of different farming methods and inform decisions in the field – yet we lack similar financial values for the cost of soil degradation, climate change, or the impact on neighboring waterways. Without those figures, it is impossible to truly compare the cost of farming regeneratively (presuming environmental costs can even be measured in dollars and cents in the first place).

“People ask me: ‘Do you get great grapes?’ I say yea. They ask: ‘Can you get a lot of grapes?’

I tell them: ‘I get as much as nature will allow me to have,’” Tai-Ran says.

As a species, our track record of accepting what nature gives us is poor. Dissatisfaction with nature’s bounty is what has historically driven innovation in the agricultural industry. This is the reason frighteningly large chickens and overburdened dairy cows exist in the first place. Given our predilection for pushing nature beyond its limits, we may assume its boundaries won’t sate us, but that may not necessarily be the case.

“I think, if enough time is spent observing and thinking about it, you can do less and still get the same quality and yield. I'm not saying I can answer that myself. I've just started the process. But that’s why I took my vineyard as an experiment down that path. It will take generations to sort this all out unless a huge group of people with an enormous amount of capital decide to put their mind to it,” he explains.

Having the Conversation

Experiment is a word Tai-Ran deliberately uses to describe Niew Vineyard. His current aim is to determine if it’s possible to manage a vineyard using Fukuoka. This is one of the reasons he is not suggesting everyone goes out and adopts natural farming – at least not just yet. “I'm not an advocate. I'm not in any way suggesting people should adopt the way I think about farming, and I'm not saying that this is the way forward. I'm saying that I find it very interesting, and I absolutely love it,” he says.

Re-concepting viticulture is quite the task, especially when there aren’t many others doing so. Some have been receptive to Tai-Ran’s ideas and to re-thinking vineyard practices from the ground up, but many are unable to shift their frame of mind and are put-off by the very idea of this discussion.

Perhaps it is because Fukuoka, while having fewer input costs, is not centered on familiar, capitalistic principals; the time scales it operates on, while finite, are much longer than traditional cycles; and the farmer’s role, while indispensable, requires profound humility and resolute trust in nature.

But seeing where the status quo has gotten us (and given the ballooning cost of farming traditionally),

Shouldn’t we at the very least have this conversation?

As a winemaker who anxiously lies awake during vintage worrying about everything from the weather to the future viability of growing grapes anywhere at all, I had to ask him:

“Is it stressful to farm like you do?”

“No, not at all,” Tai-Ran says. “I could do this forever.”

*Including proponents of regenerative, biodynamic, and organic viticulture

Photographs provided by Diana Hawkins.