Kate Burns is an Australian wine writer who now calls Canada home. She holds the WSET Diploma in wines and is an ongoing contributor to Somm TV Magazine. Kate has worked harvest in the Okanagan and is enthused by telling the stories of the Canadian wine industry, with a strong focus on sustainability.

Regeneration: The Canadian Way

Canada is not a country known for producing value-driven wines, the production costs are too high. We seldom export our quality wines as our regions are not well known. In fact, most Canadian wine is inaccessible outside of the province its produced. So what is it that makes our wine industry so extraordinary?

Our wine landscape is small though a regenerative farm is not hard to find. A regenerative farm will look different. You will not find rows of neatly manicured vines cultivated in a monoculture system. What will stand out is the wild and unruly look of the land that is trying to emulate a natural ecosystem. These plants are sentient, intelligent and self-organizing. They will survive without human intervention. Our management of these environments is what defines regenerative agriculture through an understanding of how nature, animals, and humans coexist.

We Can Be The Change

We humans, have mismanaged our resources and depleted our natural capital far beyond its means. Our planet faces a climate and nature emergency, and viticulture is vulnerable. It can easily succumb to extreme weather incidents that are becoming more prevalent, caused by our exploitive practices. Many small farmers rely on this single annual crop for survival. The stakes for them are high. It is not uncommon to see producers have their yearly grape harvest wiped out by frost, heatwaves or smoke taint. These realities highlight the delicate balance we must find with our surroundings. We need a shift in mindset from control to cooperation with our environment and communities.

“About 30 percent of the cumulative carbon humans have emitted to the atmosphere comes from centuries of transformation of land, clearing vegetation and disturbing soil to raise livestock, grow crops, and harvest timber. Human exploitation of the land still causes about a quarter of our total climate pollution.”

- Climate Scientist Kimberly Nicholas, Ph.D. Author of ‘Under the Sky We Make’

Many local Canadian farmers and producers have the prescience to understand that with collective action, our small industry can be an environmental leader through knowledge, patience, practice and community and an example of how to do better.

It's In The Soil

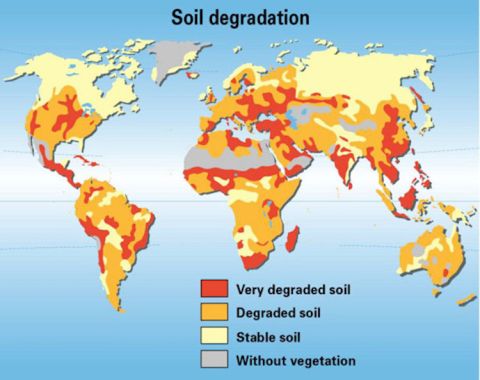

We are facing a modern emergency, and soil health is a defining factor. Desertification and soil degradation has led us to a critical point, and we are losing available cropland and the ability to sequester large amounts of carbon through healthy soils. Soil erosion from conventionally plowed agriculture fields is happening at a rate much faster than it can naturally regenerate itself.

“The nation that destroys its soils destroys itself.”

- 32nd President of the USA, President Franklin D Roosevelt

Within Canada’s Okanagan Valley is the region of Summerland. It’s an extreme place to be growing grapes with a semi-dessert climate. The summers can get hot, and the dirt below your feet is dry and dusty. Here you will find Lightning Rock Winery [pictured above, in main image], a farm created by Jordan Kubek and Tyler Knight, along with Jordan’s dad, Ron Kubek. Both Jordan and Tyler have been farming and making wine in Summerland since 2011, giving them intimate knowledge of their region.

They purchased Elysia Vineyard in 2017, which was conventionally farmed. The landscape was lifeless, and the soils were depleted, dead from having been heavily fertilized with synthetics. Elysia showed distress, needing over a thousand new vines planted in the first year. With Tyler spending most of his time in the vineyards, he began implementing a heavy compost regime and a no-till approach to bring life back to the soils. Weeds began to proliferate throughout the vineyard, creating an essential ground cover. The native plants and trees started to grow in places they would thrive. Over a short period, the vineyard began to heal and regenerate.

Canyonview Vineyard was purchased in 2018, adding to the Lightning Rock farm and the continuation of these farming techniques developed. All the winery waste, including the pomace, gets added to the robust compost pile. To help nourish this, Lightning Rock works with the neighbouring animal rescue, taking the fertilized straw to add to their compost pile. Tyler approaches his farming with an understanding of how plant systems interconnect. He doesn’t actively manage the cover crops, instead, they create self-sustaining capabilities as they would in the wild. As the wild flora flourishes on the farm, it has encouraged the native animals and insects to return to the property. Without pests on the farm, there are no predators, and without the predators, there is no fully functioning animal life cycle. The Okanagan has a large population of parasitic wasps, with over 100 species that feed on different pest insects, adding to the complex animal lifecycle.

Creating this functioning ecosystem has benefited the Lightning Rock farm in many regards.

“The last two years in the valley have been bad for leaf hopper, where vineyards have lost their whole canopy before harvest. I’ve never had to spray a single vineyard,” says Tyler.

Not only has soil life renewed with biodiversity and health and robust native animal systems returned, but these vines can cope with high environmental stress. Last June, the Okanagan suffered a heat dome, where the temperatures spiked over 45°C. These vines had the capability to survive without additional care.

The culmination of these regenerative practices shines through the glass in the electric wines that Jordan makes in the Cellar. She can take a less is more approach to winemaking with such healthy and vibrant fruit. Lightning Rock works predominantly with Pinot Noir, and their lineup includes a stellar sparkling wine program. The fruit that comes into the winery has an abundance of natural yeasts. These indigenous yeasts represent the complex microbiology that comes from a thriving ecosystem. The Elysia vineyard has a 200 ft higher elevation than Canyonview. The wind is constant, and its east-facing exposure catches the gentle morning sunlight. The soils are shallow on decomposed granite, and the wine it produces shows mineral tension. The Canyonview vineyard sits on a warmer south-facing aspect. Here, the soils are a deep sandy loam with granite river stones. The wines are opulent with a ripe fruit profile.

These sites sit just metres apart, but the expression of Pinot Noir they produced is highly nuanced. It is the intention of Lightning Rock to show how terroir expresses itself in the glass through the biodiversity of the farm.

“Terroir can be an abstract idea until you can taste it in the wines, side by side.”

- Tyler Knight, co-owner of Lightning Rock Winery

A Path To Reconciliation

What often gets overlooked in regenerative practises is the human element. But, a complete ecosystem includes fair labour practices, collaboration and work to restore indigenous culture, knowledge and land management techniques. One such winery that understands this is Benjamin Bridge. Located on the far east coast of Canada, the Gaspereau Valley of Nova Scotia is a true maritime region. From its inception, this winery held ethics of social and environmental justice for its community at the forefront. Gerry McConnell and the late Dara Gordon created Benjamin Bridge. As lawyers, they were both at the centre of creating social change through provincial and federal policy-making in Nova Scotia in the 1980s and 90s.

Creating Benjamin Bridge in 1999 was an intuitive decision of Gerry and Dara to connect land, humans and community through the lens of wine. They understood the ecosystem of this land was extraordinary, and they instinctively farmed organically from the beginning.

Benjamin Bridge is a generational winery, now in the hands of Gerry and Dara’s twin daughters, Ashley and Devon Mc Connell-Gordon. They have continued to evolve the farm with the same sensibilities as their parents, along with a collaborative and close team that includes Jean-Benoit Deslauriers as head winemaker. Benjamin Bridge is a member of Regeneration Canada and has always been proactive in looking after its ecosystem, but where they are making fundamental change is in the community. The vineyards sit on the traditional lands of the Mi’kmaq people, who have lived in this ecosystem sustainably for 13,000 years. The winery contextually understands that their 20 years of grape growing with European genetic material is arbitrary in comparison.

Benjamin Bridge has been actively engaging with the Glooscap First nation since 2017. Zabrina Whitman is a Glooscap band member, consultant, and policy advisor for the federal government on behalf of the 13 chiefs of Mi’kma’ki. She plays an important political and social role throughout the Maritimes and works with the local community on decolonization. She is also a food and wine lover and a close friend of the wineries, having been a wine club member of Benjamin Bridge since the beginning. This partnership started with anti-racism workshops for the leadership team of the winery. The learnings from this impacted their daily business operations, everything from how they approached communication to their hiring practices. From here, this friendship grew into a collaboration event, now in its fourth year. “Beyond Terroir” was created in response to a lack of representation of indigeneity food and wine and Mi’kmaq voices in the culinary scene of Nova Scotia. At these events, Mi’kmaq knowledge holders speak to guests while they enjoy traditional dishes like rabbit stew and moose loin, as seen through a modern lens.

Over these past few years, Benjamin Bridge has been building relationships with the chief, council members and elders and has learned parts of Mi’kmaq culture that help them understand how to do better. These learnings have trickled into their farming and business practices with a nuanced understanding. But these learnings are in their infancy.

As they keep moving forward, this allyship has culminated in a unique project with the release of the first collaboration wine between the Mi’kmaq First Nations and Benjamin Bridge. Zabrina facilitated the connection between the winery and the Glooscap community. The chief and council approved everything from sampling the wine to writing the text together and working on the label. Zabrina’s impact on the identity of this wine comes from within the bottle and the vital role she plays in this partnership. Benjamin Bridge’s commitment to the Glooscap First Nation community has led to the signing of a memorandum of understanding by Chief Sidney Peters and co-owners of Benjamin Bridge, Devon and Ashley Mc Connell-Gordon.

“Since time immemorial, Mi’kmaq have lived in balance within the unique ecosystem where these vineyards are now planted. This wine embodies the friendship and allyship between Benjamin Bridge and Glooscap First Nation and is a reflection of our mutual desire for a future in the image of this holistic definition of sustainability.”

- Glooscap First Nation and Benjamin Bridge Winery

Benjamin Bridge is 75% women-led, and their collaborative and non-hierarchal work environment means that every employee has a voice in the decision-making. They have transparency with the team, and no topic is off-limits, from finances to farming. The winery understands and values the happiness of its people and community. This core belief system has been there from the beginning. If their people are not well looked after, that makes a lesser wine in their eyes.

Animal Husbandry and Its Contribution to a Flourishing Ecosystem

Driving through the Naramata region of the Okanagan, you sense that this is a special place to grow grapes. Amongst the rolling hills of this small picturesque region sits the Bella farm. Jay Drysdale and Wendy Rose found inspiration in this site that had been neglected for many years before they purchased it in 2013.

The land had sufficient organic topsoil, and Jay naively thought he could just plant vines, and they would grow prolifically. But, that wasn’t the case. Neglect didn’t mean that nutrients were abundant in the soil. It was a steep learning curve to realize the best way for him to rehabilitate the land without using synthetics was to integrate animals. They began testing on a half-acre plot with a small flock of chickens. They then added pigs and ducks into the farm rotation.

Today’s livestock systems rely on feeding animals diets of grain and pallets. Alarmingly one-third of our farmland is committed to housing the animals we consume. Bella understands that creating a farm ecosystem that can sustain itself relies on the animals foraging as they would in the wild. Although these systems take time, the goal with the chickens is to have them live purely off the farm. Having them close to the compost pile is beneficial, and along with eating small amounts of vegetation, they are master insect and bug hunters. The farm has had no issues with cutworms or leafhoppers for years, and they have kept the grasshoppers to a minimum. While they hunt for bugs, the chickens fertilize the soil and eat weeds and grass, not as much as sheep or cows, but this vegetation is a vital part of their diet.

Pigs are the essence of Bella and are purchased seasonally. They travel only a short three hours to their new home in the vineyard each year. They are an Okanagan hardy breed, a mix of Lincolnshire, Durock and Hampshire. They like to be outdoors and can withstand low winter temperatures on the farm. These boisterous creatures need supervision when roaming the vines to control their impact, as they also enjoy digging up things they are not supposed to. They are vital in not letting anything on the farm go to waste. Bella works with three local restaurants taking the fruit and vegetable scraps, which amounts to around ten to fifteen buckets per week the pigs consume.

These hardy pigs will grow to around 250-300 pounds throughout the year and end up with well-marbled fat. Once slaughtered, the fresh and nutrient-rich meat gets divided among the Bella staff, with one pig going to the local community. They currently raise four per season but hope to get to eight as the farm grows.

Bella has kept ducks for the past couple of years, and their specialty is fertilizing. They are part of a pool system in which their waste is captured in water, retaining all the nutrients. It is then processed and put back into the vineyard as fertilizer. It contains high amounts of nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus, which helps build soil health and micrology. But, as nature would have it, a Bobcat attack wiped out all of Bella’s ducks earlier this year. They hope to reintegrate them into the farm system once more secure infrastructure can be built.

“Every animal on the farm has a purpose. We need to think about how we approach agriculture. I didn’t want to look at farming as what do I need to kill or eradicate to grow my fruit. I look at farming as a way to nurture and replenish. What can I add to make these plant systems better.”

- Jay Drysdale, co-owner of Bella Winery

These farmers and stewards of the land are what make the Canadian wine industry so extraordinary. They are part of a wider community of producers throughout Canada that understand that regenerative agriculture is the only path forward.