From AR$1,690, 259.90 Norwegian kroner, 269 Swedish kronor, £25, $31.99, €39

As outlined in Three generations of Argentine wine, Familia Zuccardi have their origins in the Maipú area, just south-east of Mendoza city, where Alberto Zuccardi established the business in 1963. With around 650 ha (1,600 acres) of vines in Maipú and further east in Santa Rosa, the bulk of the family’s business is there.

But it is 110 km (68 miles) further south, in the higher-elevation Uco Valley, where their focus has been over the last 15 or so years. Here they have established a series of fincas and a new bodega, completed in 2016, for making fine wines from this fashionable area.

I visited in late 2014, by which time the bodega was complete enough to have vinified a full vintage, but was still very much a work in progress, as the image above of what is now the tasting room – with its glorious Andean panorama – clearly illustrates.

The style of the Malbecs we tasted there was revelatory and, for me, exemplified a new wave of Mendoza Malbec emerging from the Uco Valley. These wines are in an elegant, floral style, lighter on their feet than the established model of inky, ripe, dense, oak-laced, power wines.

Under the leadership of third-generation family member Sebastián Zuccardi, the winemaking style here generally involves very little oak and, when it is used, it is older or larger for minimal influence – as Julia noted when making their entry-level Zuccardi Serie A Malbec 2015/2016 Uco Valley her wine of the week three years ago.

Far more important is their deployment of concrete, in the form of unlined vats. This feature led me to make their Concreto Malbec my wine of the week today. As the name implies, concrete is the sole material used to make this particular wine.

This provides a notable link to the wine’s origins, with grapes coming from the Piedra Infinita vineyard surrounding the winery. Piedra Infinita also provided stones (it is literally named ‘infinite stones’) and sand for the concrete used to build the winery. The link is particularly tangible since, in my view, unlined concrete is not entirely neutral and does impart a subtle aromatic character. Wet concrete has a distinctive smell and there is a hint of something similar on this wine. This is no criticism: it adds an attractive … well … minerality – terroir indeed!

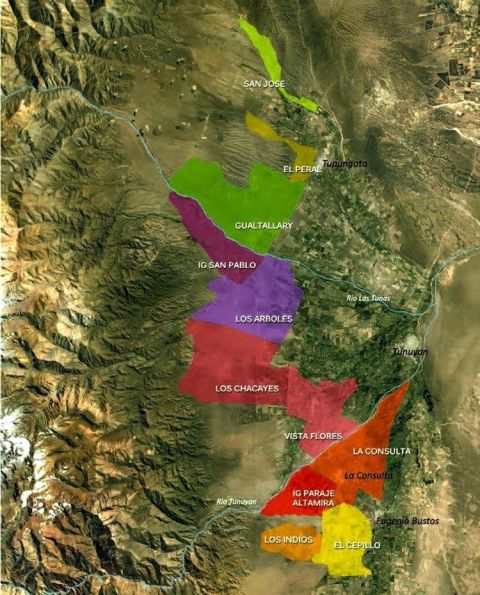

Moreover, stones and silty sand are key features of Paraje Altamira, the demarcated region in which Fincas Piedra Infinita and nearby Canal Uco sit. Originally defined in 2013 (though later enlarged after lobbying), this was Argentina’s first GI to be defined by geographical and geological features rather than political boundaries. See more here.

Paraje Altamira is a rough triangle sitting on an alluvial fan that has been criss-crossed by the Tunuyán river over millions of years. As such it is an amalgam of rounded stones up to the size of a car, embedded in silt and sand. Many of these stones are then coated with deposits of lime that have precipitated out of the Andean snowmelt over time.

Although Altamira appears to be a 10-km stretch of flat vineyards (actually around a 1% incline, rising 100 m over that distance), there is vastly more complexity beneath the surface – as the hundreds of soil pits dug around the region as part of its GI establishment revealed.

The subsoil essentially undulates with the river’s historic lines of flow, creating free-draining ‘ridges’ with large stones near the surface that alternate with ‘troughs’ containing more water-retaining silt. This can result in significant variations along a vine row in both vine vigour and ripening times.

Unfortunately, this information came too late for Zuccardi’s earlier plantings, such as Canal Uco in 2007, meaning they have had to adapt square vine blocks planted across these variations by either adjusting irrigation within rows, or harvesting at different times. But it is this attention to detail, and the progressive understanding of the vineyards they have in Altamira and other parts of the Uco Valley, that I think translates into quality in the glass, with the top-of-the-range bottlings such as Finca Piedra Infinita Malbec garnering major plaudits (albeit accompanied by a three-figure price tag).

Concreto Malbec, though sourced from Piedra Infinita, does not have such heady pricing, thankfully. The 2018, which Jancis scored 17/20, costs around £25 a bottle in the UK with lower prices elsewhere. The wine does, however, have signature features of Piedra Infinita and the wider Paraje Altamira, influenced by the 1,100 m elevation. This imbues a fresh acidity and encourages a perfumed, violet, floral character that together bring a sense of lightness to a wine despite its weight – at 14% it is no shrinking violet! That floral perfume is augmented by a second feature of Zuccardi’s winemaking here – a significant proportion of whole bunches. These add a lifted, half-herbal, half-floral scent that is, for me, distinctive when stems are present in a fermentation, and which works well here. The floral accent carries through to a good long finish that is accompanied by a savoury, flinty edge and a pinch of chalky tannins, completing a style that is a long way from the ripe, sweet-black-fruit-and-vanilla bombs of old.

As the range of currencies at the top of this article suggests, this wine is widely available in many markets around the globe and I would encourage those willing to re-evaluate Mendoza Malbec to give it a go, to get a sense of the revolution taking place here.