2023 – a year of contradictions reviewed

As consumption went down, prices went up. As water becomes an increasingly scarce resource, many wine regions were plagued by excess rainfall. As the average weight of bottles came down, the quality of what's in them went up. A version of this article is published by the Financial Times.

My leading impression of this year has been that prices of mainstream wine seem suddenly to have gone through the roof. Of course there is general inflation to be taken into account. Wine producers worldwide who absorbed increased costs of, for example, bottles and equipment for a while seem to have decided en masse to pass them on to us consumers. And in the UK, since 1 August, we Brits have had the additional imposition of a new and complex duty system tied to alcohol content which has added, pre-VAT at 20%, an additional 44 pence a bottle to most still wines.

At the same time, UK duty on champagne and other sparkling wines actually went down, by 19 pence a bottle, but I have seen no sign of this being passed on to those of us who buy it, despite the fact that over the last year or two champagne prices seem to have risen even more steeply than those of still wines. This was perhaps fuelled by the fact that investing in champagne (and, incidentally, whisky) has become a thing. Champagne price rises, incidentally, were arguably good news for producers of English sparkling wines, who have so often been accused of over-charging.

All these price rises come, contrarily, at a time when, for the first time in my long professional life, wine consumption is plummeting in key markets such as the US and the UK. There is competition from abstinence and now cannabis, as well as the alternative alcoholic drinks that are so much more interesting than when a handful of mass-produced brands of beer and spirits ruled the world. And in these difficult economic times it is becoming painfully clear to those who produce and sell it that wine is a discretionary purchase.

Even those who can afford Domaine de la Romanée-Conti burgundies have stopped buying wine at the rate they did a few years ago. According to Gary Boom, CEO of global fine-wine merchants Bordeaux Index, ‘People are definitely becoming more health conscious. We are finding even some of our favourite billionaires are drinking less.’ As proof of softening of demand, the Liv-ex price index of trophy wines peaked about a year ago and has been in steady decline ever since, with champagne and burgundy showing the steepest falls. Now that interest rates have risen, wine is no longer of much interest as an investment and London’s nucleus of fine-wine traders have been twiddling their thumbs for some time now.

Wine consumption has been falling steadily in Europe’s main wine-producing countries for decades but things are really serious now. The French drink almost as much rosé as red wine today and this has had a catastrophic effect on predominantly red-wine regions such as the Rhône, and Bordeaux, where surplus wine is being distilled into industrial alcohol and the French government has been bounced into providing subsidies for growers prepared to pull out vines. The problem is particularly acute in the Entre-Deux-Mers and the northern Médoc, where there was wide-scale conversion from mixed farming to viticulture at the end of the last century.

The last two grape harvests in much of Europe were comparatively generous, which isn’t particularly helpful (although it seems to have helped stem burgundy’s recent extraordinary price rises).

Growers all over the world are getting used to warmer and warmer summers, earlier and earlier harvests, increasing incidence of wildfires and long-term concern about the availability of water, not just in California but even in Burgundy, where some celebrated producers wonder whether they will be able to make wine at all in 20 years’ time. But 2023 was distinguished by rain – and floods that proved fatal in Romagna in Italy and Hawke’s Bay in New Zealand. Much of Europe saw so much rain during the growing season that it led to downy mildew so rampant that some producers who had carefully adopted organic methods, eschewing agrochemicals, were tempted to return to the convenience of spraying with fungicides.

The wet weather turned many vineyards into jungles, especially the increasing proportion of them with other plants grown between the rows of vines. It must have been tempting to turn to herbicides such as glyphosate (the active ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup), which has just been approved by the EU for up to another 10 years. The California winegrowing certification body Napa Green on the other hand has just announced that it will require its members to phase out the use of glyphosate by 1 January 2026.

But perhaps the biggest shock in American wine circles in 2023 was what looked like the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March. Wine may not have been nearly as important as tech to SVB but SVB was vital to vintners all over the country and especially in the leading wine state California. Although it was rescued by First Citizens Bank later in the month, the failure shook the confidence of a whole industry.

Another important wine industry has had its confidence shaken. Australian wine exports, once the envy of the wine world, are in the doldrums, the most important market China having been wiped out overnight by the imposition of retaliatory tariffs two years ago. There are frequent rumours of a détente but the Australians have taken the precaution of negotiating a trade agreement with India that excludes Australia from the punitive taxes that have long hampered the ability of India’s famous growing middle class to get their hands on imported wine. Australia is now the leading exporter of wine to India with a 42% share of the 10 million bottles imported into the country last year.

All this doom and gloom comes at a time when the average quality of wine, at almost all levels except the most industrial brands, is higher than it’s ever been. And we consumers can only benefit from an era when an increasing number of ambitious, clever people want to make wine even if they aren’t necessarily very good at selling it.

Awareness of the need to save our planet is increasing in the wine world, however. More and more wine bottlers now realise that wine’s biggest carbon footprint is the production and transport of glass bottles and barely a week goes by without some producer emailing me with news of their ‘lightweighting’ of bottles.

In October a group of retailers announced an important accord to reduce by the end of 2026 the average weight of the 75-cl wine bottles they sell to 420 g. The powerful Scandinavian alcohol monopolies are already on board, as are Whole Foods Market; Naked Wines in the US, UK and Australia; The Wine Society and Lathwaites (each extremely sustainability-minded); Lidl GB; Virgin Wines; and Waitrose, with several other important retailers nearly there. Recent signups to the accord include Terra Vitis, a French association of 2,000 winegrowers and producers committed to sustainable winegrowing whose members produce 300 million bottles a year.

A few more examples of 'lightweighters' to add to those in this earlier article. The extensive global fine-wine group Jackson Family Wines has been busy reducing bottle weights across the board and is currently testing a 397-g bottle on the line responsible for 90% of their production. A group of Alentejo producers have reduced median bottle weight from 780 g in 2013 to 520 g today and they are aiming for 420 g, while the Crimson Wine Group in the US, including names such as Pine Ridge, Seghesio and Archery Summit, is aiming to reduce bottle weight to 400 g by 2028. They reckon the industry average is 550 g and I have noticed over the last year a general considerable reduction from an era when some bottles weighed as much as a kilo.

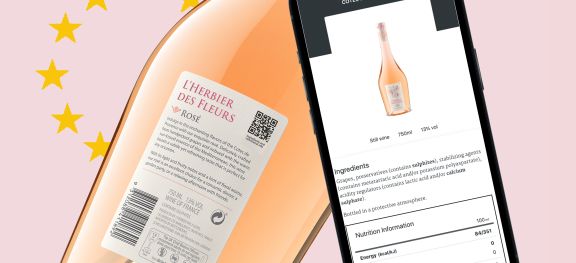

One brand-new development came into force earlier this month. Any wine produced after 8 December 2023 now has to spell out what’s in it, either on the label or, more likely, via a QR code. Your phone will now be able to tell you not just how your wine was scored but which additives it contains. Good news for those of us who are both curious and thirsty.

Jancis recommends …

We may be drinking less wine but 2023 has proved a quite exceptional year for reading about it. The books below are all great reads. Modesty would prevent me mentioning a particularly comprehensive wine reference book except that I contributed just 10% of the considerable new material in the fifth edition of The Oxford Companion to Wine (OUP £50/$65 944 pages). All praise should go to its new lead editor Julia Harding and assistant editor Tara Q Thomas.

Vintage Crime by Rebecca Gibb (University of California Press) £25/$29.95, 282 pages

Eye-opening survey of wine chicanery through the ages right up to the present day.

The World in a Wineglass by Ray Isle (Scribner/Simon & Schuster) $50/CA$70/£30, 720 pages

Urbane overview of wine today followed by profiles of the author’s favourite producers.

The New French Wine by Jon Bonné (Ten Speed Press) $135, CA$176, £112 two volumes 458 and 393 pages

Massive, deep, sometimes surprising, contemporary polemic on the current state of wine in France. The second volume is a compendium of noteworthy wines and their makers.

On Burgundy compiled by Susan Keevil (Académie du Vin Library) £30, 280 pages

Perfect holiday reading: 59 varied but relevant essays by well-informed contributors.

The Complete Bordeaux Vintage Guide by Neal Martin (Hardie Grant/Quadrille) £35/$45, 527 pages

Another great holiday read: Martin considers Bordeaux vintages 1870 to 2020 in depth and matches a film, music and an event to them. Amusingly.

Vines in a Cold Climate by Henry Jeffreys (Allen & Unwin) £16.99, 294 pages

Rollicking, sometimes entertainingly cheeky, tale of the modern English wine revolution with lots of useful technical information snuck in as well.

For detailed reviews of all these books see our guide to book reviews. EU label courtesy of Bottlebooks.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,408 featured articles

- 274,574 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,408 featured articles

- 274,574 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes