Bottle manufacturers, take note

8 June 2023 We don’t publish many heartfelt pleas but this is one worth republishing free. There may be encouraging signs that an increasing number of wine producers are aware of the need for lighter bottles, but are bottle manufacturers?

10 May 2023 A call for closer ties between those who make wine and those who make the containers for it.

In the early 1990s wine producers the world over were tearing out their collective hair over the poor quality of corks and the rising incidence of cork taint. The initial response from the cork industry was to deny that a problem existed. It took the manufacturers some years (and the prospect of diminishing sales as synthetic alternatives and screwcaps became increasingly popular) before they acknowledged that they needed to institute more rigorous cork treatments and testing protocols.

At the time I wrote a monthly opinion column for the US magazine that was at that stage still called (The) Wine Spectator and I vividly remember devoting one article to an impassioned appeal to cork manufacturers to get together with the wine industry to discuss and deal with the problem. I cited glassmaker Georg Riedel as an exemplar of a supplier to the industry who really engaged with its members. (At the time he was touring the world doing his comparative tastings of specific wine types in his and his competitors’ wine glasses.)

I certainly wouldn’t take credit for what happened, but since then Amorim and the like have truly infiltrated the wine world and are alive to its concerns, with the result that wine bottlers now have access to a much wider array of better-quality corks and the cork manufacturers’ business has grown immeasurably. Portuguese heads have been withdrawn from the sand for good.

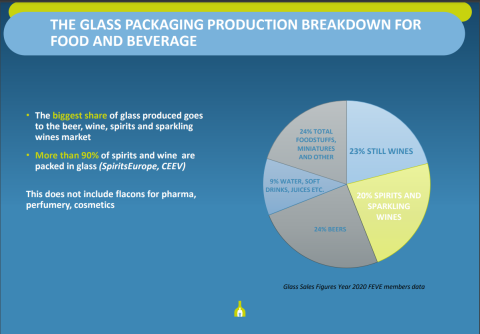

I’d now like to make a similar appeal to bottle manufacturers. Currently the relationship between them and their most important customers (see below; pharma, perfumes and cosmetics account for just 1 million tons of glass as opposed to the 23 million tons represented in this diagram) is becoming increasingly fractious. This has been driven in large part by recent stiff price increases as well as shortages and bottlenecks in the supply chain, by no means always fully and transparently explained.

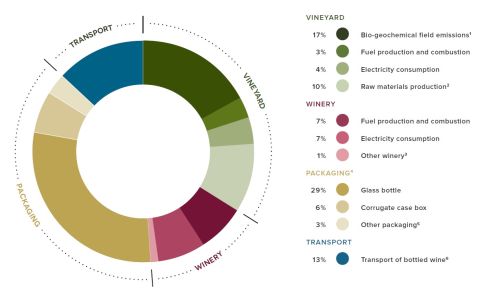

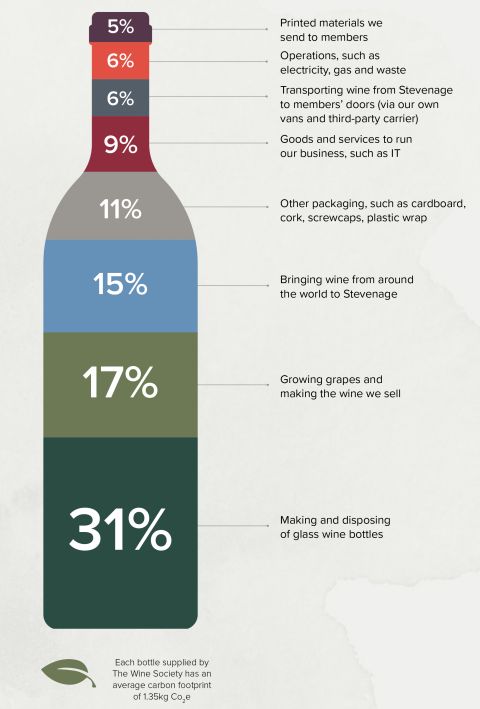

We are now familiar with the fact that glass-bottle manufacture and transport is the most significant contributor to wine’s carbon emissions, as the graphics below indicate. The first was commissioned on behalf of wine producers by the California Wine Institute, the second by UK online retailer The Wine Society. (Calculations vary slightly, not least according to where bottling and consuming takes place, but you get the general idea.)

We are pleased to have played a part in making wine producers, consumers, retailers and bottlers aware of this (see these 19 articles) so that there is now increasing interest in alternatives to glass bottles for everyday wines, as well as pressure on bottle manufacturers to supply lighter-weight bottles for wines designed for ageing (glass being the perfect, inert material for serious wine).

We have recently seen the growth of containers made from recycled plastic, aluminium and lined paper as well as increased interest in putting good-quality wine in both boxes and cans. This is not simply for consumer convenience and choice but increasingly because the carbon emissions involved in making and transporting them are much less than for the equivalent glass bottle. Santiago Navarro, promoter of the flat, recycled PET bottle, points out that according to brand owners Accolade, his package of Banrock Station performs better with regard to repeat buying than the glass bottle, and is very thrilled that The Wine Society is thinking of putting some of its own-label wines into this innovative package. (It’s not plastic itself that is evil, it’s what we do with it.)

But many a wine bottler and wine producer has tales of having difficulty persuading the glass-bottle manufacturers to supply lighter bottles. For the moment there is a shortage of moulds for lighter bottles because manufacturers still believe there is little demand for them. Smaller wine producers are also stymied by the fact that bigger bottlers have the means to buy two or three years’ worth of bottles in advance, leaving supply painfully short.

Those bottlers and producers suspect that some of the resistance is inspired by the fact that the manufacturers feel they can charge more for heavier bottles. But since lighter bottles use less raw material, surely it’s just a question of getting the pricing right? Yes, new moulds have to be designed but these lighter bottles will be increasingly demanded and the manufacturer who can supply them first will be rewarded with healthy sales.

There really is a strong argument for bottle manufacturers and the wine (and beer and spirits) industries to work together to increase sales and reduce carbon emissions, and for the glass industry to listen to the needs of their main customers. For the moment, they feel they have wine producers over a barrel (so to speak) and can afford not to take account of their concerns. How many switches from glass to cans, bags in box and recycled plastic will it take to change their minds?

That said, I have heard good things from several wine producers about European glass manufacturer Verallia, which has entered into several sustainable projects with brand owners. Purple Pagers may have noticed that, although we try to specify bottle weights as often as possible in our tasting notes, we have not so far mentioned the weight of bottles of sparkling wine since they have to be extra-heavy to withstand the pressure inside. There is good news from Champagne Telmont, who report that, in conjunction with Verallia, they first managed to reduce the weight of their bottles from 900 g (32 oz) to 835 g and have more recently successfully tested a bottle weighing just 800 g (28 oz).

Furthermore, increasing pressure from the growing cohort of environmentally concerned consumers will surely drive them eventually to accelerate investment in lower-carbon furnaces, which is long overdue considering the energy needed to keep a furnace going at scorching temperatures 24/7, 365 days a year.

There is also the much-vaunted shortage of sand, so far a vital ingredient in glass manufacture. FEVE, the association of European glass manufacturers, say they are aiming to use 95% of recycled glass instead of sand but at the moment that proportion, even in Europe where glass recycling is much more established and effective than in either the UK or the US, is only 52% on average so there is a long way to go. It would surely help all parties if those who produce drinks and those who produce glass bottles to put them in could work together – to improve the supply chain, to address the planet’s needs, and to lobby for the changes required to do so.

A few success stories

- Jason Haas of Tablas Creek has calculated that they have saved $2.2 million over 14 years, at a conservative estimate, by switching to lighter bottles. (Not music to the glass industry’s ears, admittedly.)

- At the major NZ winery Craggy Range, for long a devotee of extra-heavy bottles, they have reduced their bottles from 900 to 500 g (17.6 oz). Head winemaker Julian Grounds told me, ‘external pressure from distributors is the best thing that happened to us’, and the savings entailed by lightweighting were described by him as ‘the most powerful thing to show our owners’.

- Native Flora of Newberg, Oregon, have used a bottle weighing less than 500 g on average from the 2010 vintage and today use one no more than 467 g (16.5 oz). According to the owner, ‘we ship 90% of our production to consumers all across the USA, and only have three or four damage incidents per 1,000 shipments, or 0.2%’.

- Over 300 wineries in Styria in Austria use the unique, returnable Steiermarkflasche (Styrian bottle) for their wines. The return system was devised in 2011 by the state of Styria, the viticulture department of the chamber of agriculture and SPAR supermarkets. It saves around 6,000 tonnes of CO2 and 96% in energy consumption a year.

- Philip Cox of Romanian wine exporter Recaş reports that he buys tens of millions of 365-g (12.9-oz) bottles, which he managed to convince his local factory to produce ‘after a long struggle, but we found that 70% of a glass bottle’s CO2 emissions occur after they are produced, and things like recycling and re-use actually make things worse because glass is so heavy – the more you move it the more CO2 is emitted.’ Food for thought.

A California coda

While I was in Napa recently, I asked the Napa Valley Vintners to invite their members to submit lighter-weight bottles for my tastings there. Krupp Bros and The Vice clearly didn’t read the memo as they submitted bottles that weighed, respectively, 860 g (30.3 oz) and 750 g when empty – so would weigh about 1,610 g (56.8 oz) and 1,500 g full. Too heavy!

Those who have managed to use at least one bottle (usually for one of their less expensive lines) weighing less than 500 g (17.6 oz) empty, so about 1,250 g full, include Acre, Artesa, Grgich Hills, Honig, Markham and St Supéry. Special shout out to Grgich Hills, who use lightweight bottles for even very smart wines, and to Rosemary Cakebread of Gallica, whom I congratulated in my 2020 Napa Cabs tasting article for being determined to source US-made bottles rather than those shipped in from China, but berated over the weight of the bottle used for her 2020. She wrote last week to say she has managed to find a US-made bottle that weighs 300 g less for her 2021s, so only 500 g. Bravissima!

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,407 featured articles

- 274,950 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,407 featured articles

- 274,950 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 48-hour preview of all scheduled articles

- Commercial use of our wine reviews