Alcohol on labels – how accurate?

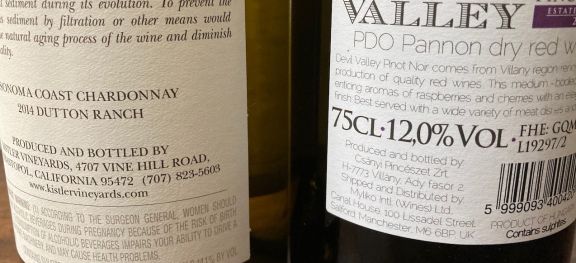

Tolerance takes on a new meaning for alcohol-conscious wine drinkers. A version of this article is published by the Financial Times. Above, the difference between alcohol-level presentation on labels in the US (left, bottom right-hand corner thereof) and the EU (right).

Alcohol may be what distinguishes wine from fruit juice, but many wine drinkers seem pretty wary of it these days. A recent global study by leading specialist researchers Wine Intelligence found that 40% of regular wine drinkers reported that they are actively seeking to moderate their alcohol consumption. But since hotter summers encourage the build-up of sugar in grapes, which yeast converts to ethanol, alcohol levels have been rising relentlessly. Wines of at least 14% alcohol by volume (abv) have become increasingly common.

Consumers take comfort in the fact that alcohol levels have to be stated on wine labels, but how accurate are they? In the EU a ‘tolerance’, or leeway, of 0.5% alcohol is allowed for most wines (0.8% for sparkling wines and those that have been in bottle for at least three years). And in the EU alcoholic strengths have to be given in multiples of 0.5%. So a wine with 13.5% on the label could in fact be higher than 14% abv.

Tolerances permitted in the US and Australia are even more generous. Percentages given on wine labels in Australia can be as much as 1.5% awry. So if a wine is labelled as 13%, the actual alcohol content could be anything from 11.5% to 14.5%. As long ago as 2008, wine writer Max Allen observed in The Weekend Australian that virtually all Barossa Shiraz was labelled 14.5% when many of them nudged 16%. He also reported that the national wine organisation was considering changing the domestic tolerance to 0.8%. But that still hasn’t happened (although the tolerance on Australian wines exported to the EU is ‘only’ 0.8%).

Within the US, where alcohol levels tend to be spelt out to the nearest 0.1%, wines under 14% alcohol are also permitted a tolerance of 1.5%, while those above 14% are allowed a tolerance of 1%. Thus a California wine with, say, 12.5% on the label could be anything between 11% and 14% in reality; and 14.7% on the label could signify anything between 13.7% and 15.7%.

It’s also worth mentioning that the type size of alcohol levels on US labels tends to be Lilliputian – a magnifying glass is often required to read them – whereas the EU mandates a decent minimum size.

I asked Damien Jackman, who is now UK Trade Director of the California Wine Institute, whether exporters of California wine bothered to convert their labels to comply with EU alcohol-labelling requirements. He pointed out that these are extremely rarely enforced. ‘In five years running Legal [requirements] for Treasury Wine Estates in the UK and Europe I think I had a German authority try to hold a shipment at a port once because the abvs on some Beringer wines from California were not rounded to [the nearest] 0.5%. I never had it raised as an issue by UK authorities.’

Most American wines exported in bottle (vast amounts of cheaper California wines are shipped in bulk to the UK where they are bottled and labelled in accordance with local regulations) tend to have their original US label on them. While UK importers occasionally superimpose a sticker with the alcohol level rounded to the nearest 0.5%, this still leaves consumers wondering how the tolerances have been interpreted.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s high alcohol levels were admired, especially by many American wine drinkers. The bigger the bang, the bigger the justifiable buck. During that era I saw alcohol levels of over 16% on some California wine labels.

Yet some connoisseurs insist that high levels of alcohol simply don’t suit certain styles of wine. Raj Parr, for example, outlawed any Pinot Noir above 14% when he ran the wine programme for Michael Mina’s restaurants in the US 15 years ago. The highly respected sommelier-turned-winemaker went on to found a movement called In Pursuit of Balance designed to showcase California wines that provided an alternative to the high-alcohol Napa Valley Cabernets (‘big wines’) proliferating at the time.

Parr and his fellow believers have spawned a perceptible reaction to the big-wine movement so that the California scene is now pretty polarised – between the old guard making big wines and the new wave deliberately picking grapes earlier to make more refreshing, lower-alcohol wines. Today Parr produces Pinot Noirs at Domaine de la Côte in southern California with alcohol levels well below 14%.

Recently I asked an insider (who requested not to be named because he did not want to be drawn into a truth-in-labelling fight) about recent trends in the discrepancy between actual alcohol and what’s on the label for the traditional big California wines. ‘There is less discrepancy than 10 to 20 years ago’, he reported. ‘Actual alcohols have come down a bit, and I think that labelled levels have come up a bit. In other words, 20 years ago the wine might have been 15.8% and labelled as 14.6%, and now the wine is 15.2% and labelled at 14.9%.’

Keen to distinguish themselves from the traditional big hitters on the cranium, new-wavers in both California and Australia (especially) positively boast about lower alcohol levels. Several people in California assure me that the new-wavers typically pride themselves on accurate labelling and transparency in general.

Meanwhile, the 25% tariffs former president Donald Trump imposed on wine imports from many EU countries in October 2019 as part of the Airbus subsidies dispute applied only to wines below 14% abv, which did not incentivise such accuracy. It is an open secret that, since then, the abvs cited on many European labels destined for the US have been massaged above 14%.

It’s also worth pointing out that sparkling wines are in a special category as far as alcohol levels are concerned. Their sparkle depends on the carbon dioxide given off by a second alcoholic fermentation when a mixture of yeast and sugar is added to (generally quite low-alcohol) base wine made from not-too-ripe grapes. The winemaker can determine the final alcoholic strength of the sparkling wine by calculating exactly how much sugar to add – which is why virtually all sparkling wines, in the EU anyway, have an alcohol level of about 12 or 12.5%. I have asked the wine trade association in the UK why sparkling wines are given a greater label tolerance (0.8%) than still wines (0.5%) and they are trying to find an answer.

In my recommendations this week, I suggest a few wines that combine character and pleasure with relatively low alcoholic strength. On the label.

Low in alcohol, high in flavour

Whites

Matthiasson, Tendu Cortese 2018 Clarksburg 12%

£17.95 St Andrews Wine Company, £19.99 The Oxford Wine Company

Exciting California answer to Gavi of Piemonte.

Zilliken, Saarburger Rausch Riesling Kabinett 2019 Saar 8.5%

£21 The Wine Society

So pure. Featherlight but the intense fruit is positively explosive. A German classic that will last for decades.

Ferdinand Garnacha Blanca 2018 Lodi 12%

£23.50 Vin Cognito

Both floral and saline, and much livelier than most southern French Grenache Blanc (same grape).

Georg Breuer, Estate Rüdesheim Riesling trocken 2018 Rheingau 12%

£24.50 The Sourcing Table

Impressive dry Riesling that’s ready to savour now from an impeccable estate.

Keep, Delta White 2019 California 11.5%

£28 Nekter Wines

Heady, intriguing blend of Grüner Veltliner with Chardonnay and Pinot Gris that finishes agreeably dry.

Vincent Caillé, Terre de Gabbro 2017 Muscadet 12%

£28.99 Handford Wines

Seriously intense, mineral-perfumed wine made in concrete eggs.

Reds

Meinklang, Roter Mulatschak 2018 Austria 11.5%

£12.95 Vintage Roots

Slightly fizzy, crown-capped light red that has proved infinitely versatile with a wide range of foods.

Chatzivaritis, Carbonic Negoska 2019 Greece 10.8%

£23.50 Maltby & Greek

Rare local Greek grape transformed, in an admirably hands-off way, into a super-fruity delight with a textured finish. Could be served cool.

Matthiasson, Tendu 2018 California 12%

£23.70 Nekter Wines, from $13.99 in the US

Sweet and sour blend of Barbera with Aglianico and Montepulciano, packaged in an admirably lightweight bottle with a compostable cork.

International stockists on Wine-Searcher.com.

See all 16 of our articles focusing on alcohol levels in wine.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,401 featured articles

- 274,903 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,401 featured articles

- 274,903 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes