Average pleasures

Wine doesn't always have to be great, argues Richard.

Most wines I taste are of average quality. Mediocre. 15.5 out of 20. Middle of the road, meh, workaday, functional, ordinary, humdrum, fine. But hardly fine wine.

It’s inevitable that the majority of items within any sizeable set of things will be average. Most meals you eat, most football matches you watch, most wines you drink – even if the last category consisted solely of grand cru burgundy, there would, comparatively, be some disappointing experiences and some transcendent experiences, but most would end up somewhere in the middle. Go on enough rollercoasters and they get a bit samey.

For many oenophiles, averageness is the enemy. After all, why would you devote yourself to something if not to pursue its uppermost echelons?

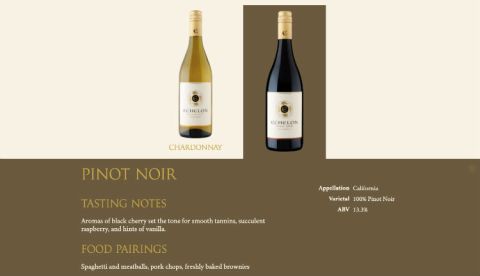

Digression*: is there a wine called Echelon, I wonder? Of course there is, and it’s from California, naturally. They don’t have a cuvée called Uppermost, sadly, although their Pinot Noir is apparently a great match with ‘Spaghetti and meatballs, pork chops, freshly baked brownies’, which makes a suitably bonkers addendum to my food and wine matching Spittoon.

(*Is there also a wine called Digression? Yep, and it’s a Provence rosé that looks like a perfume ... made for a California company.)

Anyway, the pursuit of excellence is nothing to be ashamed of. It’s only natural for the devotee of a cause to want to experience its zenith. No mountain climber wants to stop at K2. Olympians don’t lust after silver medals. And everyone who has been bitten by the wine bug is ultimately infected with a virulent urge to discover the best.

Not everyone need have the same ‘best’ in mind, of course – but for every preference there is a clear pecking order. For Cabernerds it’s Latour, Screaming Eagle et al. For Pinotphiles, DRC reigns supreme. Naturalistas might claim to be more egalitarian, but Gravner and Ganevat and Radikon still enjoy exalted status.

And so they all should. A consensus of opinion both expert and amateur testifies to the supremacy of these names. As a consequence of this reputation, these wines tend to have a price and scarcity that puts them beyond the normal reach of most wine lovers. But let’s say that cost and availability were no barrier. Whatever your preference, the best wine in the world is always at your fingertips. Your cellar is full of the finest wines available to humanity, and your freshly baked brownies are standing by.

In such a scenario, only ever drinking the best of the best, would you always be satisfied?

I’m sure some people would genuinely say yes, and I wouldn’t exactly call them wrong ... but I would certainly disagree, which amounts to pretty much the same thing anyway.

Because there is great pleasure and satisfaction to be found in the average. Well-made Côtes du Rhône and Muscadet, for example, offer a satisfying, expressive and appetising glass of wine. They remind us that wine provides a simply daily pleasure, that it needn’t always be rarefied or expensive or legendary.

Furthermore, these stalwart wines of the daily grind give us essential reference points against which we can then appreciate the more occasional wonders of the world’s finest. I remember reading Hugh Johnson’s lament that a tasting populated only by the greatest wines inevitably results in them being compared with each other, some therefore unfavourably – yet any one of them should, by themselves, be a beacon of quality. Is it really worthwhile knowing which vintage in a 20-wine vertical of La Tâche is the best? Or do each of those 20 deserve the attention afforded to a virtuoso soloist, perhaps only preceded by a good Bourgogne as a warm up?

Average wines surely have their place, then – but that leaves us with the question of how you identify the ones that are really worth buying? Indeed, can you even know how much better-than-average they are without having tasted all the others by way of comparison?

Well, having a database of nearly 200,000 tasting notes, as we do, certainly helps. But the question of how to find the best wine at an average level is wine’s great conundrum, and the reason why it remains an enigmatic, intimidating, infuriating and compelling subject.

Anyone can discover the world’s finest wines. Simply accumulate sufficient dosh and they will magically seek you out via the kindly merchants that sell them for a living. But finding the best, most interesting average wines – that is knowledge really worth having.

It will never be straightforward, and that is an intrinsic part of wine’s appeal. The point is that an outright dismissal of average wine would be to deny one of its fundamental pleasures: the quest for those unassuming bottles that defy expectations and deliver a shock of liquid pleasure; reminding us that sometimes, the joy of wine can come as much from the rest as from the best.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,406 featured articles

- 274,946 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,406 featured articles

- 274,946 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes