In the heart of western Romania lies Banat (see this World Atlas of Wine map), a somewhat neglected vinicultural treasure bordering Hungary that’s recently emerged from a long period of neglect.

I discovered this hidden gem, Romania’s smallest wine region, last November when I went to Timișoara to attend ROVINHUD, a wine tasting organised by self-advocacy group Ceva de Spus in support of Romanian children with disabilities. (The 2023 event raised an admirable €35,000. You can read more about this initiative in Jancis’s 2015 account of her earlier visit.) Located only about 24 km/15 miles from Timișoara, Banat is an easy drive and well worth the trip – especially given that only around 6% of Romania’s wine production is exported. If you’d like to taste the wines, the best way is to go to the source.

History

Legends claim that the region is the birthplace of Bacchus, the wine god of the Dacians, some of the earliest inhabitants of the region, who was then adopted by the Greeks as Dionysus. The oldest written documentation of the region’s vineyards is dated 11 November 1447, a writ recording the sale of the vineyards from Ioan and Catherine Magyar to Michael of Ciorna, Ban of Severin, for 32 Hungarian gold forints.

The region’s winemaking fortunes took a downturn with a devastating phylloxera outbreak in 1888. The communist era and, in particular, the reign of notorious dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu further hindered its development. During that time, private property was banned and all wines were produced in co-operatives.

The region still holds reminders of its better days, such as the slightly eerie town of Buzias, now known for the abandoned spa that once attracted visitors seeking relaxation, healing and wine. On the way out of Timișoara, we were tailed by a Russian-era IFA van – to me a typical symbol of countries with a recent history on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain. Yet the region is also beautiful, with gentle hills rolling peacefully capped with little chapels scattered here and there.

According to Philip Cox, owner of Cramele Recaș winery and one of the Banat’s staunchest supporters (more on him below), a significant development in the rebirth of the region was EU funding for vineyard redevelopment. This funding began after Romania joined the EU in 2007; between 2010 and 2020, over 1,000 ha (nearly 2,500 acres) were replanted in Cramele Recaș’s vineyards alone, and it is estimated that at least 4,000 ha were planted throughout the entire Banat region.

The past decade has seen the opening of numerous new Banat wineries, supported by EU financing and encouraged by convenient transport links and greater access to markets in Western Europe since joining the EU. This growth has brought greater diversity, improved quality and a stronger emphasis on premiumisation.

Banat terroir

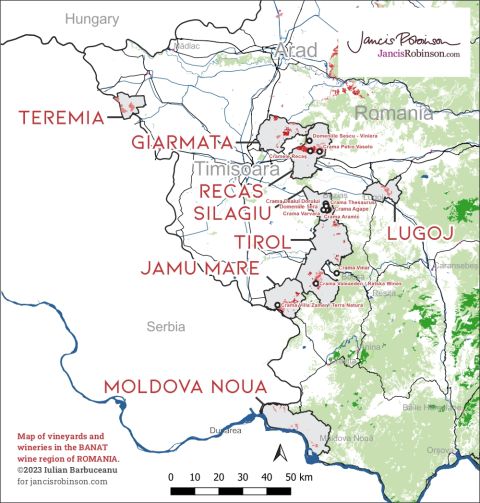

The Banat region spans approximately 28,526 km2 (11,014 mi2), with 1,498 ha (3,702 acres) registered as DOC in 2023 according to the National Office of Vine and Wine Products. A significant part lies within Serbia: the region was partitioned after World War I, with the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. Portions of Banat were incorporated into Romania, a very small part into Hungary (although this part doesn’t function as a wine region today), while the Serbian portion became part of Vojvodina.

Nestled within the Carpathian mountain range, the Romanian side of Banat is extremely diverse, with vineyards on the slopes of the south-western hills, in the Semenic and Poiana Ruscă Mountains to the east, the Lipovei Hills and Mureș to the north, along the Danube to the south and spreading out along the flatter Timiș countryside to the west.

Soils range from marl, clay, sand and gravel to loess. The vineyards sit at elevations of 100–350 m (330–1,150 ft), and encompass a great diversity of mesoclimates, from continental to Mediterranean. Banat is generally warmer than Romania’s other regions, with over 2,100 hours of sunshine annually. Humidity also plays an important role, with generally good rainfall levels during the winter and early summer and mainly dry weather during autumn.

Banat’s wine regions

Within Banat, there are two DOCs: Banat (307 ha/758 acres), with subregions Moldova Nouă, Dealurile Tirolului and Silagiu, and Recaș (1,191 ha/2,943 acres).

The Recaș DOC is the best known, not only due to its relative size but also its accessibility, being the closest wine region to Timișoara, where there is easy access to major transportation routes and international airports. The region is additionally helped by its long-standing reputation for quality wines, first established by the Swabians who settled here in the 1700s.

While that reputation was lost under communism, the region’s co-operative has been recuperated by Philip Cox, a Bristol native who moved to Romania in 1991. Working in partnership with a Romanian family, he relaunched it as Cramele Recaș in 1998. Since then, it has become one of the country’s best-known wineries, with 1,250 ha of vineyards in Recaș and long-term contracts with five other wineries in eastern Romania serving as crush partners. Including these partner wineries, the company produces wine from approximately 2,800 ha (6,920 acres).

It’s also one of the most forward-looking, experimenting in both vineyard and winery. It cultivates varieties such as the indigenous Fetească Regală and Fetească Neagră as well as varieties new to the region such as Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Negru de Drăgășani, a red grape variety developed in 1993 in the Horticultural Research Institute Drăgășani and that Cramele Recaș were among the first to plant. This freedom to plant new varieties has been a competitive advantage for Banat compared with other European regions with strict legislation that limits their choices. Wines such as their Pasari Chardonnay/Fetească Regală blend well-known varieties with lesser-known local ones, making it easier to introduce Romanian varieties to the export market.

They’ve also taken advantage of the local climate to explore its abilities with Pinot Noir, planting 72 ha (178 acres) dedicated to four clones of the variety (777, Dijon 113, Dijon 114 and a Geisenheim Institute clone designed to resist rot). This has allowed them to achieve the holy grail of the wine business: a varietally correct Pinot Noir that retails for under €10 (see their 2022 Zana Pinot Noir).

In 2018 the winery began producing vegan wines and wines from organically farmed grapes, and introduced Orange Natural Wine, a low-sulphite wine fermented partly in terracotta amphorae. More recently, Cramele Recaș introduced a bottle made out of plastic reclaimed from the Danube. Much lighter than its glass counterpart, the bottle is being used for a fresh, fruity Cabernet Sauvignon being sold in Germany.

The Banat DOC is far smaller and currently less developed, though that’s quickly changing. Most of the action is taking place in the subregion Silagiu, a hilly region of calcareous and terra rossa soils that was once highly regarded for wine, boasting 579 ha (1,431 acres) of vineyards at its height in 1919. Silagiu translates to ‘the village situated in three valleys’. The vineyards benefits from a climate moderated by the nearby Timiș and Bârzava rivers, as well as the hills of the Western Carpathians.

Today the region stands out for the number of small wineries popping up across its hills, such as Thesaurus, established in 2005 (with its first wines introduced in 2014), which was under the direction of South African winemaker David Lockley until recently, when he left to set up his own old-vine project. Another noteworthy venture is Crama Aramic, founded in 2010 by father and son Adam and Cosmin Crǎciunescu. Like most producers in the area, these two wineries grow international varieties such as Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon but are increasingly focused on reviving local varieties.

One of the newest is Agape, founded in 2016 by Adalbert Marton, a former winemaker for Crama Aramic. Adalbert has also spent time in Italy, studying agronomy and completing a course on biodynamic agriculture with Michele Lorenzetti.

He’s now become a leader in organic viticulture in the area, educating others as he expands biodynamic practices in his own vineyards to include sheep, ducks and chickens this year. The wines he produces from his 6 ha (15 acres) in the Silagiu Hills are some of the most impressive I tasted during my trip, from a vibrant, grapey Welschriesling to an aromatic, richly textured Chasselas 2021 from vines planted in the 1970s that clocked in at only 11% alcohol – especially impressive given the warm climate. In contrast, the 2021 Fetească Neagră is a big, purple-hued wine redolent of roses, violets, black cherries, pickles, bay leaves, vanilla and smoke. Tank-fermented and aged in French oak for 16 months, the wine is fresh yet elegant, with a long, umami finish and well-integrated tannins.

I recommend visiting this charming region as it emerges from its 100-year beauty sleep. It’s easy to get to from Timișoara airport, and local wineries welcome visitors for tastings with advance bookings. Take time to visit Cheile Nerei-Beușnița National Park, where you can explore the stunning Bigar Falls, an 8-metre (26-foot) cascade of water that falls over moss-draped stone. Additionally, Danube cruises provide breathtaking views of the monumental rock sculpture of Decebalus, an enormous tribute to the last king of Dacia, who defended the country against the Romans.