Biodynamic viticulture in the Americas

22 June 2023 Continuing today’s biodynamic theme, we’re republishing this illuminating history free in our Throwback Thursday series. Sam has been on study leave this month, preparing for, sitting and recovering from the MW stage two examinations – fresh contributions from our Pacific Northwest correspondent will resume shortly.

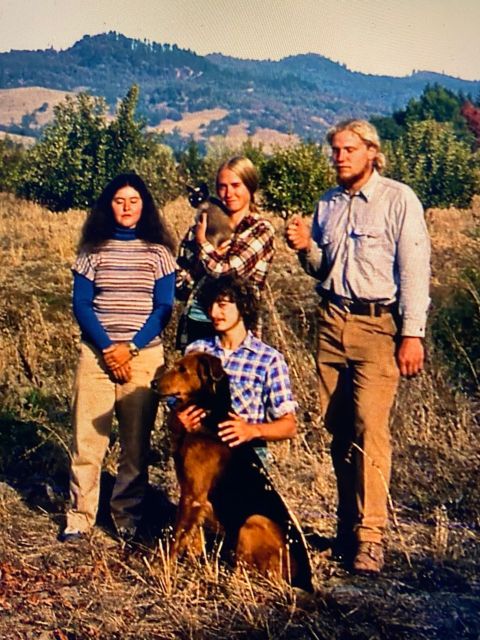

28 February 2023 How Ehrenfried Pfeiffer and Alan York primed the Americas for biodynamics and regenerative farming. Above, in a photo shared by Rodrigo Soto, York stands among several fellow proponents of biodynamics. From left to right: soil specialist Pedro Parra; Rodrigo Soto; soil microbiologist Claude Bourguignon; York; Anne-Claude Leflaive and Antoine Lepetit, in 2011.

‘I think, when we have the advantage to look back on this with the perspective of time, this era of “modern agriculture” will be seen as the shortest-lived system that has ever been pursued.’ (Alan York, 1997)

Biodynamics is a divisive topic, even among its practitioners. On one hand you have the practical elements of farming without industrial inputs – a focus on composting, cover crops and homeopathic preparations, combined with strict limitations on pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and fertilisers. Most people agree that these elements are impactful to overall farm health. On the other hand, biodynamics can include wholly unprovable spiritual and metaphysical elements. It is these elements which can lead to derision for the entire practice.

As someone who has followed the recent groundswell of support for regenerative agriculture (and supports it myself), I’ve listened to fellow supporters lambast biodynamics without recognising that the history of biodynamics in America is inextricably entwined with the history of modern organic and regenerative viticultural practices. While Regenerative Organic Certification (ROC) launched in 2020 and could be said to be a more scientific and comprehensive certification than Demeter, it wouldn’t exist without work done by biodynamic practitioners.

Our collective awakening to regenerative agriculture has been built on decades of practical experimentation, observation and collaboration from a handful of biodynamic and organic practitioners. Nowhere is this more traceable than in the Americas, where the biodynamic viticulture movement can be traced back to a single consultant by the name of Alan York … But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Austrian beginnings

Pesticides, herbicides and fertilisers have been around for centuries. As the population boomed and people relocated to cities, humanity looked for ways to enable fewer farmers to feed a growing number of non-farming people. But the use of such treatments soared after World War I, especially following the innovations made by German scientist Fritz Haber.

Drawing on Justus von Liebig’s mineral theory of plant nutrition (in which he identified nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium as essential macronutrients) and Carl Sprengel and Liebig’s ‘Law of the Minimum’ (which established that a plant’s growth is limited by the scarcest nutrient), Haber set his sights on creating a nitrogen fertiliser to help feed the world’s growing population. In 1909, he succeeded. The synthesising of ammonia, from nitrogen and hydrogen gases, became known as the Haber-Bosch process and is currently responsible for sustaining the food base for half of our global population. However, as the machine used to scale fertiliser production was finished in 1913 and ammonia nitrate is one of the world’s most explosive materials, it was used for war efforts for the following five years. Haber’s considerable brainpower was put to work perfecting the use of chlorine, phosgene and mustard gas as chemical weapons. By the time the war ended in 1918, chlorine and phosgene were being experimented with as components in pesticide manufacturing. Industrial agriculture and war had become inextricably linked.

Following the war, Haber’s chemical innovations began to spread, and the opposition was born: farmers who thought that the mercury fungicides, ammonia fertilisers and lead arsenate, chlorine and phosgene pesticides they were being sold had a deleterious effect on their soils and their families (there were quite a few poisonings from the lead and mercury). Austrian philosopher Rudolph Steiner met these farmers, learned from them, and in 1924, gave a series of lectures titled, ‘Spiritual foundations for the renewal of agriculture’. While Steiner’s lectures were what was immortalised, his formation of an international agricultural research group called the Experimental Circle of Anthroposophical Farmers was far more important. This group created and spread the first comprehensive system of non-chemical farming.

Crossing the Atlantic

Dr Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, one of Steiner’s pupils, began working with Steiner in 1922 on what are referred to as biodynamic ‘preparations’, nine herbal-, mineral- and animal-derived formulations created to nourish and sustain soil fertility. He, along with two other pupils of Steiner, made the first batch of what is now called 500 prep – aka ‘horn manure’ – and is arguably the most well-known of the preps used in biodynamic farming.

By the time Pfeiffer moved to the US to escape German advancements into France in 1940, he had been converting land and experimenting with ways of building fertility for years. Settling in upstate New York, he established the Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association and began consulting for municipal composting plants nationwide.

To make biodynamics easily accessible he created Pfeiffer Compost Starter, a compost inoculant containing seven out of the nine preparations. He also began to advise R I Rodale, who founded Organic Farming and Gardening Magazine in 1942 and is today widely considered the father of organic farming in the US.

By the end of World War II, Pfeiffer was well established as an advisor and consultant to farmers seeking an organic or biodynamic approach. When the US government began implementing aerial DDT sprays to combat insect-borne diseases, it was two of Pfeiffer’s students – Marjorie Spock and Mary T Richards – who, having observed a negative impact on avian and aquatic life, mounted a case against the government. They lost the case, but shared all their research, contacts, and trial transcripts with Rachel Carson, who used them as the primary source for Silent Spring, a book largely credited with catalysing the environmental movement after its publication in 1962. Unfortunately, Spock, Richards and Pfeiffer’s extensive contributions went unacknowledged in Carson’s influential work, and so biodynamics received little attention in the resulting movement towards organic agriculture.

California-bound

As the movement towards organic agriculture swelled, so did anti-war, anti-capitalist sentiments. California became the epicentre of liberal thinking. Universities in California began to overflow with discontented students, many of the men using the education loophole to dodge the military draft to Vietnam. Unemployment grew by choice (hippies were anti-work).

In 1965, the UC system, attempting to productively channel this discontent, opened the University of California at Santa Cruz (UCSC) to siphon off the more radical thinkers from the mainstream UCs. The campus was built in an isolated location and was devoted to a more experimental education without a graded curriculum.

Two years in, the campus hired Alan Chadwick, an Englishman who was tutored by Steiner, to develop a teaching garden. Chadwick, a revered biodynamic practitioner (though he never used or taught preparations) focused on observation, crop rotation, composting and conservation of resources.

Though the curriculum at UCSC was experimental, teaching organics in a UC system was still seen as flying in the face of scientific progress. Parents complained that Chadwick was luring their children away from more lucrative careers. Faculty complained that Chadwick was ruining the scientific curriculum. When I spoke to Paul Sansone, one of Chadwick’s students from this time period, he told me, ‘The university system told him that he couldn’t discuss biodynamics and that he had to give his lectures as theatre. He wasn’t given access to lecture halls. When the university kicked him out because they didn’t want organics in the UC system, [Herbert] Koepf continued the lectures at night, after the rest of the campus had gone to bed.’ Chadwick was forced to leave UCSC in 1972.

When Chadwick established a garden project in Covelo, California, in 1973, students he had met at UCSC followed him. Two of his former students, Jonathan Frey and Katrina Van Lente (who later married and started Frey Vineyards), joined the project in 1976. While there they met Alan York, who had been living in a commune in Santa Barbara where Chadwick occasionally lectured during his time at UCSC. York had apprenticed himself to Chadwick a few years prior and was the head of the east garden block at Covelo. When the three students parted company a year and a half later, it was without the knowledge that they would become the first people to integrate biodynamics into viticulture in the Americas.

Biodynamics in the vines

Jonathan Frey’s family had purchased a farm in Mendocino in 1959 and had planted vineyards in the 1960s to have something to claim for insurance if a dam that the federal government was building happened to flood the property. Grapes were sold to neighbouring wineries. When Jonathan and Katrina Frey left Covelo in 1978, the two struck a deal with the family that a few acres of the farm were theirs, rent free, if they worked to improve the property. The next year, their grape contracts fell through, and Jonathan Frey began making wine with the fruit they couldn’t sell. Today, Frey Family, still family owned and run, farms 350 acres (142 ha). They were the first winery in the US to certify under Demeter in 1996.

While the Freys were developing their biodynamic vineyards in northern California, Alan York cycled through teaching and farm management positions in Michigan and Missouri before returning to California in the 1990s. He began to work for an apple farm in Boonville in Mendocino, where he met Jim Fetzer. Fetzer’s family had founded Fetzer Vineyards in 1968 and had begun implementing organic practices under Michael Maltas (who had worked with Ehrenfried Pfeiffer) in 1986. After the company sold to the Brown-Forman Corporation in 1992, Jim Fetzer started his own project called Ceago Vinegarden (now known as Bonterra). Maltas recommended that Fetzer hire York. When I called Jim Fetzer, he told me that when he met York he said, ‘I’ll teach you everything I know about grapes if you teach me everything you know about biodynamics.’

At Ceago Vinegarden, Jim Fetzer continued to sell grapes to Fetzer Vineyards. This meant that York met many winemakers and viticulturists from Brown-Forman as they cycled through Fetzer Vineyards, staying months or years. He formed relationships with Fetzer’s president Paul Dolan (who, inspired by York, would go on to sit on Demeter’s board and help found ROC), Mike Benziger of Benziger Family Winery (which bought grapes from Ceago, and whom York would begin consulting for in 1997), and Álvaro Espinoza of Viña Carmen in Chile. This last relationship would lead to the spread of biodynamics in South America.

The US to Chile and back again

Over Zoom, Espinoza explains to me that he was hired by Viña Carmen in 1993. At the time, Brown-Forman was their US importer, and they brought him to California to promote the wines. While visiting, he toured Fetzer Vineyards and met Dolan. The two hit it off so well that Espinoza began to return annually. His interest in organics was such that he began to handwork a two-acre (0.8-ha) parcel at Viña Carmen by himself. In 1996, he bought his own property, Antiyal, and began farming it organically. Following the Chilean harvest in 1997, Viña Carmen granted Espinoza a six-month sabbatical to work the growing season at Fetzer Vineyards. He became closer with Jim Fetzer and Alan York and an interest in biodynamics took root.

Returning to Chile in 1998, Espinoza remembers a year that laid the groundwork for Chile’s success with organic and biodynamic viticulture. He began making wine and consulting for Emiliana Organic Vineyards, helping them to take the first steps towards organic certification. The same year he was approached by Rodrigo Soto, a graduate student whose thesis was on biological controls in organic agriculture; Espinoza’s two-acre parcel at Viña Carmen was the only organically farmed plot he could find in Chile. Espinoza agreed to allow him to run trials and gave him a harvest position. While working at Viña Carmen, Soto asked if Espinoza could connect him in California. Soto recalls that within minutes, Espinoza was on the phone with Dolan, who said, ‘tell him to get a visa, I’ll take him for eight months’.

After harvest, Soto flew to Fetzer Vineyards. By the time he finished his internship, he, too, was friends with Dolan, Fetzer and York. A month into his next internship Jim Fetzer called and told him, ‘After you’re done over there, come back. I’ve got Álvaro consulting on winemaking. Alan is in the vineyards. I want you in the cellar.’ Soto returned to California and finished out the 1999 vintage at Ceago Vinegarden.

Espinoza and Soto returned to Chile invigorated with the idea of biodynamic farming. Espinoza began to implement York’s protocol on his own vineyards and convinced Emiliana that they needed to hire York as a consultant. Soto, interviewing for a job as the winemaker at a new project called Matetic Winery, brought a slideshow of Ceago Vinegarden. ‘How do we do this?’ was Jorge Matetic’s question when Soto finished. ‘We bring Alan York here’, Soto replied.

In 2000, York became the biodynamic consultant for both Emiliana and Matetic. Not only did his clients credit him with improving the quality of their vineyards, but his work also proved that biodynamics could be scaled for viticulture (Emiliana is the largest biodynamic and organic estate in the world). Further, his influence in Chile extended beyond direct impact. Inspired by York’s work, Christian Matetic’s wife convinced her family to convert their new project, Koyle Winery, to biodynamics.

York’s influence spread. Espinoza connected him to Colomé in Argentina, which became the first winery in Argentina to be certified biodynamic under Demeter (though they were later forced to give up their certification due to issues with leafcutter ants, the most cited hindrance to organic viticulture in Argentina). York later consulted for Chakana and Altos Las Hormigas in Argentina – both of whom achieved organic certification for the vineyards they own, with Chakana eventually receiving Demeter certification.

In addition to consulting for the first biodynamic wineries in Chile and Argentina, and aiding the spread of biodynamics in California, York’s consultation helped establish the first biodynamic vineyard in Oregon. In the 1990s, York’s relationship with Mike Benziger led him to Oregon to consult on a property which Benziger had bought and planted in the Willamette Valley. While Benziger sold the property to Hawks View before starting a label, the time York spent there had a knock-on effect. Bob Gross’s Cooper Mountain Vineyards neighboured the Benziger property. Gross convinced York to consult for them. In 1999, the property became the first Demeter-certified vineyard in Oregon.

The practical appeal

In the first years of the 21st century, biodynamic consultants from Europe began to work in the US. But what is important about York is that he emphasised the practical elements of biodynamics, broadening the appeal, turning sceptics into believers, and creating enough of a belief in the biodynamic system that there was demand for more consultants. The spiritual elements, he told his clients, were theirs to discover and practice as they wished. Even the preparations, he maintained, came after conservation of resources and infrastructure.

‘He was convinced that you must master your craft before you utilised preparations. You had to manage cover crops before burying cow horns’, Soto told me.

Alberto Antonini of Altos Las Hormigas was even more emphatic.

‘Biodynamics can be too complicated at the beginning. When Alan arrived at Altos Las Hormigas he explained that we didn’t have to talk about preparations because we needed to fix things. His first great lesson was that if you don’t prepare your infrastructure you can’t get to biodynamics.

‘In Argentina, he showed me a clear example of what we were trying to achieve: a vineyard that was planted 100 years ago and was a masterpiece. Next to it, a vineyard developed by a modern agronomist that was dead within 25 years. Alan explained that the use of synthetic chemicals broke our soil chain. You need to create the environment that people did a hundred years ago, and, for that, observation is the key. Everything that’s wrong with farming is remote – all the Excel spreadsheets, not spending time in the vineyards; you’re not observing anymore. You must recover the spirit of observation. This can explain things that science has trouble explaining. Most of Alan’s knowledge came from observation.’

In 2014, York passed away, leaving large swaths of the organic and biodynamic communities in the Americas grieving. But his work continues to ripple outward. Biodynamics in viticulture, and in agriculture in general, have gained such popularity that producers across the Americas, never having heard of Pfeiffer, Chadwick, York or the Freys, have begun their own study groups and implementation of biodynamic practices. Contemporaries of York, such as René Piamonte in South America (1961–2020) and Philippe Armenier in the US (who helped introduce biodynamics to Washington State) continue to push the spread of biodynamics forward. ROC, though a different certification system, is a testament to the work biodynamic and organic practitioners have done in the last century. As both ROC and Demeter grow in popularity, the question should not be which of these is better. The question should be how we continue to turn the dirt of ‘modern agriculture’ into the soil of the 21st century.

*In 2022, Demeter had certified 560.1 ha/1,384 acres in Argentina, 1,334.3 ha/3,297.1 acres in Chile, and 1,811.4 ha/4,476.1 acres in the US.

Epilogue

In 2006, Soto caught himself checking his watch for the first time in six years. In that moment, he realised that Matetic’s team could handle anything; they didn’t need him anymore. He resigned and went to pick up York from Espinoza’s house. When Soto told York that he’d resigned, York called Mike Benziger and told him that he’d found someone to fill his head winemaker position. Soto moved his family and for the next six years took over as director of winemaking for Benziger. In 2012, Soto returned to Chile and began converting Veramonte Winery to organic and biodynamic practices. When that property sold to González Byass, he returned to the Napa Valley to take over as estate director of Quintessa. Soto and Benziger remain close friends.

Espinoza continues to consult for Emiliana as well as run Antiyal. He makes an exquisite sparkling wine, Media Noche, in partnership with Julio Bastías of Matetic.

Paul Dolan acquired Jim Fetzer’s Ceago Vinegarden for Brown-Forman in 2000. In 2004 he left the company and went on to buy his own property, Dark Horse Vineyard, converting it to biodynamic practices. In 2017, after serving on the board of Demeter for years, he helped to launch the Regenerative Organic Alliance and, in 2020, ROC. Truett Hurst Winery, a project Dolan founded with Philippe L Hurst, was one of the first estates to be ROC certified. Dolan’s commitment to ROC comes from a place of wanting the practical aspects of biodynamics to be accessible and attractive to everyone.

Recommended biodynamic wines with ties to this story

Antiyal, Kuyen 2018 Maipo, Chile 14.5%

Emiliana, Gê 2017 Colchagua, Chile 14.6%

Matetic, Coralillo Pinot Noir 2018 Casablanca, Chile

Quintessa 2018 Rutherford, California

Truett Hurst, Estate Zinfandel 2019 Dry Creek Valley, California 15.5%

Acknowledgements

This piece could not have been written without personal interviews with: Alberto Antonini, Philippe Armenier, Julio Bastías, Paul Dolan, Alvaro Espinoza, Jim Fetzer, Jonathan Frey, Bob Gross, Rudy Marchesi, Antonio Morescalchi, Juan Pelizatti, Paul Sansone and Rodrigo Soto.

Bibliography

Acres USA: Interview with Alan York. Balancing resources efficiently & creating a self-sustaining system: the nuts and bolts of biodynamics. Acres USA, April 1997.

Alan Chadwick: A gardener of souls. Accessed 1 October 2022.

Château Monty: McNab Ranch. Accessed 1 October 2022.

Chadwick, Alan. Performance in the Garden. Logosophia Press, 2007.

Day, Bill: Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, the Threefold community, and the birth of biodynamics in America. Biodynamics, Fall 2008.

Demeter USA. Accessed 1 October 2022.

King, Gilbert: Fritz Haber’s experiments in life and death. Smithsonian Magazine, 6 June 2012.

Louchheim, Justin: Fertilizer history: the Haber-Bosch process. The Fertilizer Institute, 19 November 2014.

Paull, John: The Rachel Carson letters and the making of Silent Spring. SAGE Open, 3(3), 2013.

Paull, John: Lord Northbourne, the man who invented organic farming, a biography. Journal of Organic Systems, 9 (2014).

Solovitch, Sara: Meet Alan Chadwick, the high priest of hippie horticulture. Modern Farmer, 17 August 2015.

Strayer, Pam: In memoriam: vintners mourn death of biodynamic consultant Alan York. Organic Wines Uncorked, 12 February 2014.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,408 featured articles

- 275,024 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,408 featured articles

- 275,024 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 48-hour preview of all scheduled articles

- Commercial use of our wine reviews