East meets WSET: how Asia learns about wine

Richard looks into the expansion of wine education across Asia.

In a country so keen to learn about wine, it’s ironic that jancisrobinson.com is blocked on some free wifi networks in Singapore. Here, as across Asia, wine is still sometimes viewed with suspicion, and as its popularity increases educating people about wine becomes more and more important.

Wine’s Asian invasion might be rapid, but it’s happening on very different scales across the region. Singapore, as a small city-state with a strong British influence, has a mature and sophisticated wine market. Chinese wine consumption is growing at breakneck speed in the major cities, but the vast majority of the population remains oblivious. Whereas in India, wine is still very much in its infancy.

But there’s no question that the market potential is massive, making it a very attractive proposition for wine educators. But in cultures where wine is so new, are traditional European approaches of learning about wine still relevant?

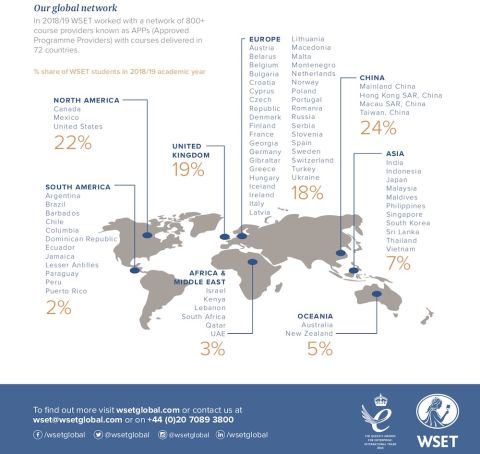

The Wine and Spirit Education Trust (WSET) would seem to think so – the map above shows their authorised programme providers across Asia. In the last academic year, the largest proportion of its students – more than 25,000 of them – were based in mainland China. Their qualifications have become the global standard for wine education, and the ‘systematic approach’ to wine tasting which they codified has given the wine world a standardised language of wine analysis.

While their programmes continually evolve (their flagship Diploma qualification was recently given a significant overhaul), none of the content is specifically tailored for Asian markets. As a result, students learn to describe wine using flavour references that may be very unfamiliar. Sonal Holland MW, one of India’s foremost wine educators, who went through the WSET programme, estimates that around 20% of flavours are unfamiliar to Indian consumers. She recalls having to buy liquorice and blueberries on trips to London to learn how they taste.

However, she also points out that aromatic descriptors for wine are usually figurative rather than literal anyway, so unfamiliar flavours needn’t be a barrier. It just means that students might learn the taste of a wine style first, and describe it using terms which they subsequently have to go and discover.

For Indian wine drinkers, this is no disadvantage, according to Holland. Alongside marriage, education is the most important life goal for Indian consumers, especially an internationally accredited qualification such as the WSET courses. Furthermore, the beverage industry is increasingly seen as a viable career path. Drinking alcohol is culturally familiar, but normally in the form of whisky and beer, so wine still has a long way to go – and education is seen as paramount to improving the prospects of wine.

One disadvantage of WSET courses in India is their cost. As a professional qualification, employers can be reluctant to fund their staff because they are unable to enforce a minimum term or repayment agreement (any such contracts are illegal in India). Yet there are almost no alternatives to the comprehensiveness and prestige of the WSET. Most other wine education courses (Cape Wine Master, Italian Wine Scholar and so on) have a regional focus which is too specific for the more general requirements of the nascent Indian wine industry.

Another disadvantage might be making the WSET’s necessarily academic style appeal to consumers. Reducing wine to a series of measurements – medium-minus intensity, medium-plus acidity, medium-minus tannins, medium-plus body etc – might be precise (and, importantly, easily markable), but it strips wine of all the romance and culture that is such an integral factor in its appeal.

Much of the appeal of wine to Asian consumers is what it represents: a fashionable, aspirational and sophisticated western drink. In that context, the most important things to learn are the stories behind wine. While the WSET does cover that to a certain extent, it is no substitute for wine in an experiential, social setting such as winemaker dinners or vineyards visits.

Both options are on the increase across Asia too. China and India both have vineyard areas on their doorstep, which already offer comprehensive oenotourism experiences. Plus, there is no shortage of visiting winemakers eager to impress their brands on a new and enthusiastic audience – in under four months of living in Singapore, I’ve been invited to events hosted by Ch Haut-Brion, Solaia, Opus One, and Vega Sicilia among others.

In fact, the thirst for learning about wine is such a rapidly growing phenomenon in Asia that three of the seven most recent winners of the WSET Vintner's Cup are of Asian origin – and female too, incidentally. It may not be long before the east is teaching the west a thing or two.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,434 featured articles

- 274,222 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,434 featured articles

- 274,222 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes