How sweet is that Alsace wine?

21 September 2023 We are republishing Julia's 2021 article today because of the latest controversy in Alsace over sweetness and labelling.

The revised regulations governing AOC Alsace and AOC Alsace Grand Cru production were published in the Journal Officiel on 1 August this year, but French law allows two months from this date for any objections to be received by the INAO (on paper, by post) and for the revised regulations to be overturned. Pierre Gassmann, of Domaine Rolly Gassmann, argues that the changes threaten traditional styles of naturally sweet Riesling, as the maximum permitted residual sugar for wines labelled Riesling (other than for late-harvest, ie Vendanges Tardives, or botrytised, ie Sélection de Grains Nobles, styles) has been reduced from 6 to 4 g/l, or from 12 to 9 g/l as long as total acidity expressed as grams of tartaric acid per litre is not more than 2 grams below the residual sugar content – ie dry-tasting, by EU and INAO standards. This is irrespective of the requirement for the sweetness indicator described below. If, like Gassmann, you wish to oppose this change, you can read more here and download the petition from the link below. Sign it, add your name and address, then email the petition as an attachment to rollygassmann@wanadoo.fr – well before the 30 September deadline. They will print and send your petition to the INAO.

9 December 2021 Now, at long last, we have an answer to that question.

Alsace wine producers are to be legally obliged, from the 2021 harvest, to indicate on the label the sweetness level of their wines using a ‘standardised sweetness indicator’.

How many times have you hesitated about buying a bottle of Alsace wine because you weren’t sure how dry or sweet it would be, or whether it would go with what you were planning to eat? If you are like me, then you’ll have lost count. Surely sales of Alsace wines have suffered because of this?

Foulques Aulagnon, export marketing manager for the Conseil Interprofessionnel des Vins d’Alsace (the CIVA, the promotional body for Alsace wines) explained that the CIVA and the AVA (Association des Viticulteurs d’Alsace, the producers’ union) have for 20 years or more been writing to Alsace winegrowers to tell them how important it is to give clear information about their wines.

Some producers have understood this and attempted to solve the problem for their own wines. I seem to remember Olivier Humbrecht MW, a long-time campaigner for greater transparency in this matter, once used little bee drawings and then a sweetness scale on bottles of Zind Humbrecht, and some producers use or have used the International Riesling Foundation’s Taste Profile, which is based on a sugar:acid ratio rather than absolute numbers (see Jancis’s 2008 article Riesling sweetness scale launched) but there has never been a consistent approach, let alone a mandatory one, across the region.

Those who objected to any sort of indication of sweetness – most often those who don’t export – justify their inaction in various ways, according to Aulagnon.

- On my back label I can talk about the food and (my) wine pairing. It’s not necessary to talk about the sweetness…

- Everyone knows that we are producing pure bone-dry white wines!

- My wine is very well balanced and se déguste en sec (tastes dry even if it isn’t), but with the EU scale, it’s considered an off-dry wine … and my potential clients, buyers won’t be interested by an off-dry wine…

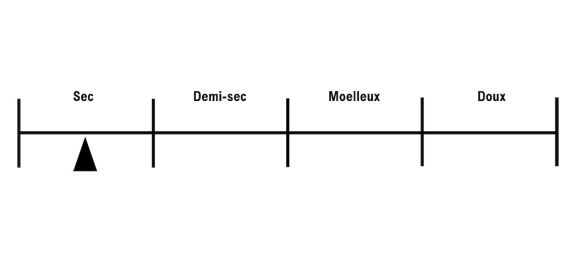

An Alsace legal order of 28 May 2021, ‘supported by the Alsatian wine industry’, according to Aulagnon, makes it mandatory for all producers of wine labelled AOP Alsace or Vin d’Alsace, to use one of the EU-regulated terms, listed below, or the visual scale shown above and below, to tell consumers how sweet or dry their wines are. (Alsace Grand Cru wine are currently excluded from the ruling because of ‘administrative procedures’ but that is very likely to change soon.) ‘The displayed sweetness guide will have to be visible, clear and standardised, and each producer will have to indicate this using one of the following two options.’

In words

These are the terms set out in the EU labelling regulations of 2009. ‘Mellow’ seems to be the euphonious Alsace interpretation of what the EU system categorises as medium or medium sweet (French moelleux). The categories are not based solely on sugar levels but also take into account the level of acidity (expressed in grams of tartaric acid per litre in the definitions below).

Dry: if the sugar content of the wine does not exceed 4 g/l (or up to 9 g/l if the total acidity is not more than 2 g/l lower than the residual sugar content, eg total sugar content up 9 g/l if the total acidity is no less than 7 g/l, or up to 8 g/l sugar if the total acidity is no less than 6 g/l).

Medium dry: if the sugar content of the wine is between 4 g/l and 12 g/l (or 18 g/l if the total acidity content is not more than 10 g/l lower than the residual sugar content, eg 18 g/l sugar if the total acidity is not less than 8 g/l).

Mellow: if the sugar content of the wine is between 12 g/l and 45 g/l.

Sweet: if the sugar content of the wine exceeds 45 g/l.

Visually

Two versions are possible but it must be unambiguous.

EU logic?

It has always been mandatory to state the dryness/sweetness level on sparkling wines because, as the EU regulations point out:

Consumers often make purchasing decisions based on the information provided concerning the sugar content of sparkling wine, aerated sparkling wine, quality sparkling wine and quality aromatic sparkling wine. The indication of sugar content should therefore be compulsory for those categories of grapevine products while it should remain optional for other categories of grapevine products.

It is still optional for still wines under EU law and only compulsory if a member state passes its own law, which is why Alsace has taken so long to get to this point. (See The Oxford Companion to Wine’s dosage entry for the mandatory labelling terms for sparkling wines.)

I’m really not sure why the EU made that distinction though the rule-makers explain it thus:

The sugar content of grapevine products other than sparkling wine, aerated sparkling wine, quality sparkling wine and quality aromatic sparkling wine is not an essential element of information for the consumer. It should therefore be optional for producers to indicate the sugar content of those grapevine products on the label. However, in order not to mislead the consumers, the voluntary use of terms related to the sugar content for those products should be regulated.

I wonder who on earth came up with that (and got paid to do so)?

Aulagnon is pleased and relieved about this development. He wrote to me: ‘That’s definitively the good news that we were hoping for for a while, and now it has become reality. Now the consumers, and the trade as well, will be enlightened by this EU scale, which is not just about the residual sugar but also about the balance in the mouth, including the tartaric acidity.’

As the CIVA’s press release says, ‘This new and attractive feature aims to make it easier for millions of consumers to choose their wines, help less expert professionals to navigate the industry and simplify the food-wine pairing process.’

It seems highly likely that this was the overriding argument that persuaded those producers not keen to go along with this. Let’s hope this improves the fortunes of Alsace wines around the world, wines that are so often lauded but whose quality is not as often recognised in what we actually buy.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,420 featured articles

- 274,421 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,420 featured articles

- 274,421 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes