We were enjoying an excellent dinner at Fallow, a recently opened restaurant in St James’s Market, when my eye was caught by the swift movement of a man seemingly waltzing around the tables.

He was definitely in his mid 60s from the colour of his hair. He was well dressed and he seemed totally at ease. He would seat the customers; he would signal to waiters to bring over menus and wine lists; he wore a constant smile; and he seemed very much at ease, so that his actions seemed designed to make his customers feel at ease.

It must have taken me an hour to realise that this was none other than John Davey, a man who has spent almost the last 40 years either performing such front-of-house roles or training many in his approach, an approach that combines an appreciation of the setting, doing something nice for his customers, and making sure that, at the same time, they and all the team ‘have fun’. I invited him to lunch to hear more of his professional approach.

Davey’s family is Irish – he still remembers affectionately the warmth of the hospitality he and his sister enjoyed as they were taken around relations on their visits to Ireland – but he was born in Bristol. ‘Useless’ at school, and excited only by appearing in a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Davey began a City and Guilds course, which he passed with distinction. But his career turned when he was seconded to the kitchens of Avonmouth Docks. There he graduated from frying bread to cooking breakfasts for the dockers and he was hooked. A stint at a Trusthouse Forte hotel followed that cemented his fascination with the hospitality business. When a lecturer called for volunteers for a nine-month stint in a grand Swiss hotel, Davey found himself raising his arm.

Here, at the five-star Hotel des Trois Couronnes, he began as a ‘commis’, the lowest of the low, carrying trays of food from the kitchen to the waiters to serve. There followed a stint at the equally splendid Lausanne Palace, where he quickly learnt what has today become a fundamental principle. ‘Any restaurant, whether it has a view of Mont Blanc or a rainy London street like the one we are sitting in, provides the most fantastic setting. And it is up to you, from the moment you walk into that setting, to dress it to the best of your capabilities. That is your challenge, twice a day, to make that room look as appealing as it possibly can’, he explained.

It was in 1977 that his Swiss wife heard that a new restaurant was about to open locally and encouraged Davey to apply for a job as a waiter there. Successful, he soon found himself manager of what many considered at the time, and many still do, to be the finest restaurant in the world.

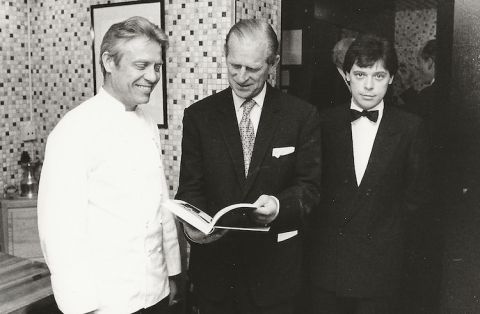

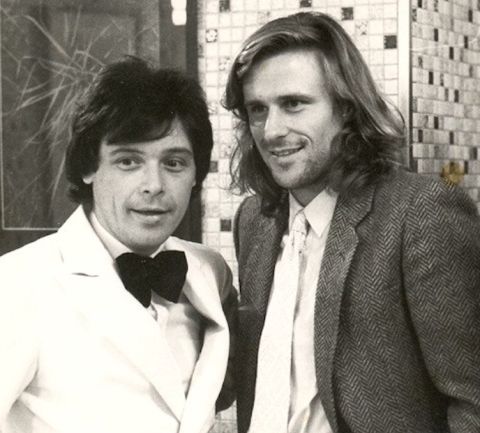

This was Frédy Girardet’s restaurant in Crissier, where Davey’s charm and ease – plus his English, once the phone calls became international – soon made him invaluable. A phone call from Washington DC led to him welcoming the late President Nixon; his charm secured him a second copy of a book signed by the late Prince Philip; and he looked after a long-haired Bjorn Borg, as well as rubbing shoulders with the likes of Pelé, Bowie and Niven.

The star-studded decade with Girardet reinforced several beliefs. Firstly, that it does not cost anything to be polite, to be attentive to guests. And while the well known expect to be treated as though they are special, it can be even more worthwhile to treat similarly those who do not expect it. At The Ledbury one evening he recalls a party of three arriving before the restaurant had opened. Ignoring the protestations of the receptionist, he brought them in, let them listen to his briefing and took them on a tour of the kitchens before seating them. It was an evening they would never forget.

Davey returned to London at the invitation of the late Sir Terence Conran to open Bibendum before moving on to Mossiman’s, The Lanesborough, The Square and Cecconi’s, then in 2008 founding his own consultancy. He admits with a twinge of regret that he never opened his own restaurant but, he confessed, ‘I’m not much of a businessman’.

But at a time when restaurant staff are in such short supply, Davey’s career and his experience ought to be followed more closely.

‘As a restaurant manager, when you walk into a room you are in charge, and you have to use every faculty to make yourself so: your ears, your eyes, your hands. It can be magical, this process of transformation, which can involve checking all the lightbulbs and the state of the lavatories. And at the same time you have to remember to be the mentor to your staff that you would have wanted to be when you were learning.’

He recalls the name of his mentor, Maurizio Santambrogio at Lausanne Palace, with affection but wonders whether the levels of hospitality in the UK have been overlooked as the emphasis has shifted so much to what happens in the kitchen.

Davey’s pet hates in restaurants are shared by everybody: too-long waits for the menu or the bill, a lack of product knowledge on the part of the waiters, and a general lack of attention. ‘Hospitality is easy’, was his constant refrain throughout our encounter. ‘It is inexpensive but it has to be fun.’

He smiled when he recalled a comment he recently overheard from a colleague as he was spotted walking into work, ‘Look, Grandad’s in tonight’.

Davey is indeed a grandfather, of four, who has had four knee replacements. But he does not regret a second of his many long hours in some of the best restaurants around the world.