Saving the Restaurant – a new film

SOMM TV's latest production focuses on how the pandemic has devastated the hospitality industry.

In February 2020, Jancis and Nick's last pre-pandemic travels were to California. Writing about the trip afterwards, Nick declared his love for the restaurant Miminashi in downtown Napa. With its Japanese-style cuisine, and fun, casual approach to dining, Miminashi had gained increasing attention. It was written up in local as well as national newspapers and magazines, named one of the best restaurants in Napa Valley, and celebrated in multiple restaurant award lists. With so much attention, the restaurant was not just a locals’ favourite. It had become a destination.

Miminashi was the brainchild of chef Curtis Di Fede, who’d previously also helped launch seasonal Italian-inspired Oenotri, also in downtown Napa, and worked in dining for decades. But by November 2020, Di Fede announced Miminashi would close permanently. Lack of funding support for hospitality during the pandemic made it impossible to stay open.

The closure of this beloved restaurant is just one example of the plague COVID-19 brought to American restaurants. By late 2020 more than 100,000 restaurants in the United States were shuttered. In March 2021, it was announced that in California one-third of the state’s restaurants had permanently closed.

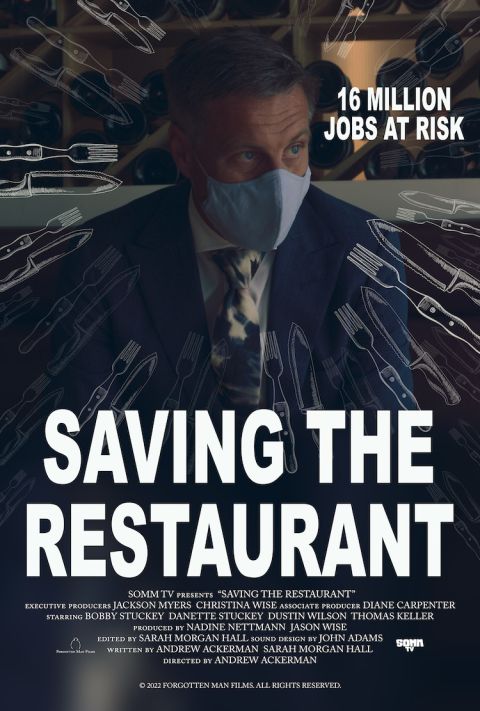

The just-released movie Saving the Restaurant on SOMM TV gives a first-hand account of the struggle restaurants face to stay open during the ongoing pandemic and helps make sense of how crucial they are to the economic health of the nation. The film follows restaurateur and Master Sommelier Bobby Stuckey (pictured above) for the first year of the pandemic from March 2020 to March 2021.

Stuckey opened the much-loved, Friuli-inspired restaurant Frasca in Boulder, Colorado, in 2004. In 2019 Frasca was awarded the prestigious James Beard Award for Outstanding Service. Besides Frasca, Stuckey also leads Pizzeria Locale, also in Boulder, and in Denver both Tavernetta and Sunday Vinyl.

Just over an hour long, the film was directed by Andrew Ackerman and written by him and Sarah Morgan Hall. Ackerman has filmed other short documentaries including another on Stuckey’s life in restaurants titled The Bus Boy, filmed in 2019 and also available on SOMM TV. Stuckey is well respected for continuing to work on the floor of his restaurants even after receiving his Master Sommelier certification. (He’s often heard encouraging his staff before a night of dinner service by saying, ‘let’s bus some tables’. Hence the name of the earlier film.)

Both films give a behind-the-scenes look at Stuckey’s day-to-day life. Where The Bus Boy focuses on what it took for Stuckey to reach the pinnacle of respect in American restaurants, Saving the Restaurant now reveals the struggle to stay there.

Saving the Restaurant follows Stuckey as he grapples with first shuttering his Boulder- and Denver-based restaurants during the lockdown, then helps form the Independent Restaurant Coalition (IRC) just two days later. We watch as he comes to terms with the responsibility he faces for his 225 employees, and then takes on what he sees as an effort to save as many of the 500,000 independent restaurants in the United States as possible. He speaks to the state governor, multiple senators and congressmen, appears on national television, speaks on numerous Instagram Live and Zoom sessions. At the same time, he works out how to do curbside pick-up service, then opens to limited seating, and eventually serves customers in yurts outside in the Colorado snow.

The film includes interviews with a few American luminaries of food and wine with personal connections to Stuckey, including Thomas Keller of The French Laundry (where Stuckey worked prior to opening Frasca) and Dustin Wilson MS (who got his first sommelier job from Stuckey). More revealing though are the observations of Stuckey’s wife Danette, who provides personal insight into her husband’s motivations.

The tension Stuckey and other members of his team feel over the course of the year is palpable. Filming moves between gritty moments following Stuckey and his team members, some of the tensest developments and the dazzling mountainscapes where Stuckey runs. We watch as confusion over government loans and grants mounts, as a restaurant-specific bill put before Congress fails, and restaurants around the nation begin to shutter. And then we see hope for new possible funding increases with the inauguration of a new President and a new Congress.

The result is evocative. We can feel the strain of the year, the relief when small victories are won, and the reality that the work still isn’t done. It’s a worthwhile insight for anyone wanting to better understand the struggles faced by hospitality these last two years.

If there is a downside to the film, it is that its subject might seem too niche. Anyone unfamiliar with the restaurant business or how loans and grants worked during the pandemic may feel a bit thrown without explanation of all the details. But the film isn’t meant to teach us the business as much as make us realise how much the restaurant business matters. We’re meant to leave the movie recognising its subject isn’t niche at all.

Restaurants are sometimes thought of as a luxury, and may be for those who dine out. But they are also a backbone of the American economy. At the start of 2020, more than 11 million people across the United States were employed in independent restaurants. Just a few months into the pandemic one in every four jobs lost across the nation was from the restaurant community. According to Stuckey, before the pandemic the hospitality business employed 15 times more people than the airline industry. Yet, when COVID-19 relief efforts were announced by the US government, the airline industry received billions of dollars while restaurateurs struggled to find reliable funding.

But the economic impact of the restaurant industry doesn’t stop at the dining-room door. Every restaurant also indirectly employs farmers, ranchers, fishermen, delivery-truck drivers and more. It is estimated that the restaurant industry supports at least five million jobs nationwide through the rest of the supply chain.

But restaurants, of course, also sell wine. For establishments with wine, beer or liquor licences, beverage orders can amount to half of total sales or sometimes more. When the pandemic hit, the loss of restaurant wine sales for wineries here in California, Washington and Oregon threatened wine businesses. Multiple well-known vintners ready for retirement realised their sales channels weren’t as diversified as they’d previously thought, and retirement was no longer an option. The complexities of the supply chain and the US distribution system mean it isn’t quick or easy for American wine producers to move wine sales from on-premise to off. Some wineries found their way into retail while many others struggled to. In the UK, changes in sales channels seemed to happen more easily. (See, for instance, all those listed in our long 2020 list of Wine retailers who'll deliver to self-isolators.)

The struggle for the American restaurant industry is ongoing. It parallels the challenges for hospitality worldwide. In spring 2021, President Biden signed the Restaurant Relief Fund (RRF) providing industry-specific assistance for hospitality. The RRF received 372,000 applications from restaurants nationwide in 21 days. But by the time 36% of the applications had received some grant assistance, the fund ran out of money.

Today, 17 February, SOMM TV is hosting two screenings of Saving the Restaurant in Denver followed by a Q&A with Stuckey and producer Nadine Nettmann. Stuckey and his restaurants have such a passionate local following that the screenings, held in aid of the Independent Restaurant Coalition, sold out almost immediately.

The group continues to work to increase awareness of how essential restaurants are to the nation’s economy, and to try to get Congress to refill the RRF to help save more independent restaurants.

The film is now streaming on SOMM TV. See this trailer.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,409 featured articles

- 275,057 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,409 featured articles

- 275,057 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 48-hour preview of all scheduled articles

- Commercial use of our wine reviews