Steven Spurrier (1941–2021)

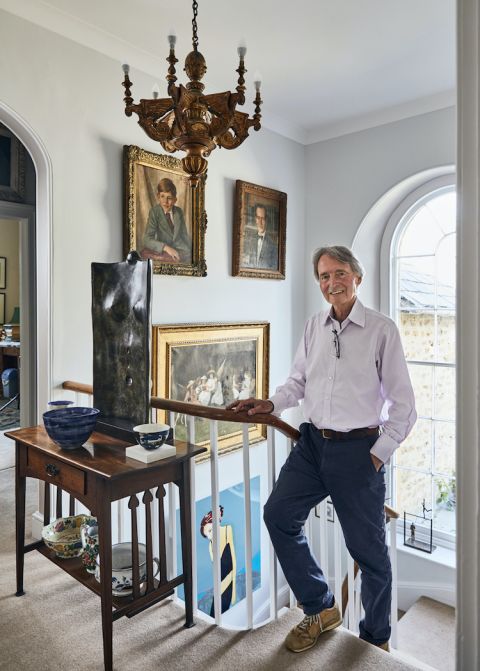

The wine world lost one of its great adventurers last night. Steven Spurrier is pictured above with his wife Bella in their Dorset garden with some of the art he commissioned. All photographs by Lucy Pope.

It seems extraordinary that the wine world is going to have to survive without someone who has been characterised for his 79 years by the phrase ‘youthful enthusiasm’.

It is likely, however, that Steven will henceforth be recognised as an even greater influence on wine than during his colourful life. For someone who achieved so much, he acted with such extreme modesty and politesse that there was always a danger of his not being accorded his due.

Even though his famous Paris tasting in 1976 was truly ground-breaking, signalling infinite possibilities for wines other than the French classics, and he was valued throughout the world as an educator, taster and writer, he wore his achievements exceptionally lightly – always more fired up by the next project than by those of the past. Indeed, when I asked him during our last conversation last Saturday night what he would most like to be remembered for, he rather downplayed the Judgment of Paris in favour of his most recent achievements, the Académie du Vin Library publishing imprint and the relaunched Académie du Vin wine school in Canada.

At any sparsely attended tasting of the most obscure, nascent wine region, Steven would be there. At the Christie’s wine courses he was delighted to run for his mentor Michael Broadbent MW, a British successor to his seminal Académie du Vin wine school in Paris where the flame was lit for generations of wine luminaries, it was Steven who carried the cases and pulled the corks.

I remember that the only time Nick and I stayed with Steven and his wife Bella at their house in Dorset – in 2014 when he sold me the Viala et Vermorel ampelography he had bought at a local sale – there was discussion over Sunday lunch of Steven’s forthcoming trip to South America. He would have been 73 then but was insistent that his hosts had no need to fork out for a business-class ticket for him. He maintained, incidentally, that it was partly his modest in-flight requirements that helped get him his job as wine consultant for Singapore Airlines. Despite, or perhaps because of, his materially comfortable upbringing, he was the opposite of a prima donna.

He had the manners of an Old Etonian and debonair was a word made for him (as was his London address, Playfair Mansions) but in fact it was to the famously sporty public school Rugby that his well-heeled parents sent him, two years behind another wine-obsessed aesthete, Hugh Johnson.

As he admits in the first edition of his autobiography A Life in Wine, he was a debs’ delight and a not particularly engaged student at the London School of Economics. He knew ever since he tasted a glorious Cockburn’s 1908 when he was 13 that he wanted to work in wine and started out at St James’s importer and bottler Christopher’s on £10 a week. Also in 1964 he met his wife Bella. In the same year he and his brother were each presented with a cheque for the equivalent of £5 million today on the sale of a family gravel company.

This helped him indulge his love of art, on which he admits spending far more than on wine, and gave him the confidence to follow all sorts of wine ventures throughout his life – not always profitably. As he wrote, ‘As 1966 drew on, my large inheritance began to slip through my fingers. The decisions were all mine, but I always expected the results to be better than they were. I was an easy target for adventurers who needed backing for a nightclub or for making a movie …’

What really set him on his way in wine was his purchase in the early 1970s of a wine shop in Paris called Cave de la Madeleine, backed by Bella who by then was living in France with him (a barge on the Seine was their first Parisian home). At La Cave de la Madeleine and L’Académie du Vin wine school he opened next door, he became famous, particularly among Paris’s considerable anglophone population, as a champion of the lesser-known wines he would travel to find all over France. Those whose wine journeys began here in the Cité Berryer side-street near the Madeleine include France’s most famous wine writer Michel Bettane and some of the British wine trade’s most celebrated names.

But Steven will be most vividly celebrated for the tasting of top California wines he and director of L’Académie du Vin Patricia Gastaud-Gallagher organised to celebrate the bicentennial of the United States in 1976. Their initial purpose was to show off to some of France’s most celebrated palates what California vintners were already achieving. But a week before this seminal tasting on 24 May (when my diary tells me I attended a tasting of Argentine wines in London and was revising for a WSET exam) Steven decided that the French might be prejudiced against these American upstarts. So he fatefully decided to include some of France’s best wines and turn it into a blind tasting. California triumphed in the most convincing/humiliating way and thus was wine history rewritten. Ex-student of L’Académie, journalist George Taber, described the event in Time magazine under the heading The Judgment of Paris and wrote a book of the same name. Indeed, wine lovers are much more likely to have heard of this tasting than of the tale from Greek mythology.

But Steven achieved so much more than this. He may have been cold-shouldered by the French wine establishment for a while (and was never given the formal French honour he so richly deserved), but his knowledge and connoisseurship were so evident that they could hardly be ignored. His love of French wine could not have been greater (as witness his enviable cellar in Dorset) and he was accorded full privileges when we tasted together as we did for years in the Bordeaux en primeur circus. That youthful enthusiasm was always delightfully and usefully in evidence as our fluctuating group was poured the latest vintage and some comment called for.

I couldn’t possibly mention all of his various enthusiasms throughout his long life in wine. He opened wine bars in Paris, where his various business ventures ran aground and left him with a massive tax bill. He went into the wine business in the US but fell foul of the three-tier system there. When he and Bella moved back to Britain in 1990 he was briefly hired to beef up the Harrods wine department but was fired for not being suitably deferential to the owner Mohammed al-Fayed. A project for a wine-based tourist attraction in disused railway arches near London Bridge was right up Steven’s street. He suggested its name, Vinopolis, invested in it, and urged everyone he met to do the same. It was completed to an admirably high standard in 2000 and limped along before finally closing in 2014. An Italian Académie du Vin was wound up in 2008 and The Wine Society of India was too far ahead of its time. A Japanese Académie du Vin that was more successful and continues to this day illustrates the geographical reach of Steven’s fame.

Arguably the most permanent of Steven’s many enthusiasms is Bride Valley, the vineyard he planted on the Dorset hillside opposite his and Bella’s house in the winter of 2008–2009. The first vintage was 2011. The second a literal washout. Mildew shrank the 2017. And so on. But, as ever, Steven remained resolutely optimistic about his future as an English vigneron and Bride Valley is now firmly established as a superior English sparking wine.

Although frequently deputising for Michael Broadbent when he was invited to attend wine events around the world, Steven was probably most readily associated with Decanter magazine for which he first wrote in 1993. He had a monthly column and tasted and travelled widely on the magazine’s behalf. By 2004 he managed to persuade the magazine’s then-publisher Sarah Kemp to launch a wine competition to rival the International Wine Challenge, also based in London. The Decanter World Wine Awards, with Steven at the helm, have been a massive commercial success, providing substantial and much-needed entry-fee income as print advertising shrivelled.

In 2018 Steven persuaded a friend to publish his memoirs. He was in such a hurry to see them in print that this initial edition suffered from a serious lack of editing and did not sell well (see Tam's review). Typically, he was inspired by this setback to attempt book publishing himself, thrilled to discover that he could still use the name Académie du Vin. This new enterprise went through several commercial iterations and is now run by Simon McMurtrie, publishing several new editions every season.

One of the finest and most poignant of the many books published by this new publishing imprint is a second, sensitively and adroitly edited edition of Steven’s memoirs, A Life in Wine. I thoroughly recommend it, not just for the collection of moving and revealing tributes to a great man of wine at the beginning but because it gives you such a distinctive, true flavour of his enthusiasms and restlessness. He quotes with some pride his daughter Kate’s observation, ‘your problem, Dad, is that you’re bored by the present’.

During my last conversation with him I was struck by his phenomenal memory and generosity. He reminded me that my husband Nick had been the second person to visit him, after Sarah Kemp of Decanter, when he was in hospital after a cycling accident outside the Victoria & Albert museum, and that I had described him in this FT profile as ‘an unsung hero’.

From his bedroom, ‘surrounded by paintings that I chose and love’, he told me, ‘I was a privileged boy and I had a lot of luck. But I have loved wine – and art – all my life, and the wonderful people I have been lucky enough to meet and perhaps inspire.’

He died just after midnight last night and will be sorely missed – particularly at London’s more obscure professional wine tastings.

The family assure us that a memorial will be held in due course.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,401 featured articles

- 274,903 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,401 featured articles

- 274,903 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes