A transatlantic Israeli wordsmith

Nick compares the New York and London branches of a restaurant inspired by the Tel Aviv food scene. A torch was needed for Lilienblum's red mullet, shown above.

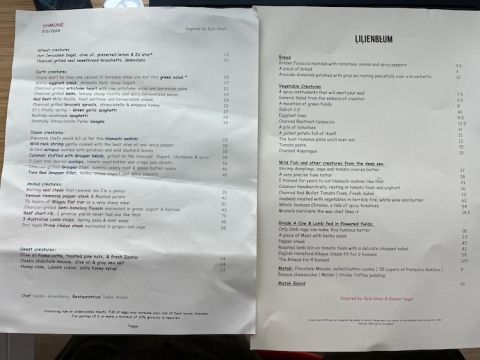

These two menus, from Shmoné (Hebrew for eight) on New York’s W 8th Street and Lilienblum (a street name in Tel Aviv) on London’s busy Old Street roundabout are both examples of the creative talents of the Israeli chef and restaurateur, Eyal Shani. The one on the left, brought back across the Atlantic, is rather less pristine than its London counterpart.

They both fulfil the primary aim of any menu, which is to bring a smile to the customer’s face. If it achieves this, then the restaurant has gained an easily winnable advantage. And the first time I saw the menu at Shmoné I laughed, albeit quietly. I had never before seen a menu divided into wheat, earth, ocean, animal and sweet creatures. I smiled at the prelude to the green garlic spaghetti: ‘it’s finally spring’. I liked the use of the different typeface for a green salad about which was promised ‘there won’t be even one second of boredom when you eat this’. All good fun. Shani clearly enjoys menu-writing.

I expect little modesty from Israelis, so I smiled again when I saw ‘Japanese chefs would kill us for this’ about his hamachi sashimi, and the melting veal cheek that ‘reminds me I’m a genius’. I also liked the fact that this menu was dated correctly; that it paid homage to the source of its inspiration in the top right-hand corner; and that it listed at the bottom not only the chef, Nadav Greenberg, but also and quite exceptionally the name of the ‘restauratrice’, Talya Avisar.

By comparison, Lilienblum’s menu seemed a little duller although there was a hint of bravado in ‘the best hummus plate you’ll ever eat’ and although Shani was credited there was no mention of the chef, Oren King. The typeface they have chosen seems a little regimented, a little too formal.

But the biggest difference in the pleasure generated by these two restaurants lay in the spaces themselves, admittedly accentuated by the very different weather on the nights we visited.

As I met my friends on West 8th Street on a Monday evening, we could have been anywhere on the Mediterranean coast. It was early May but it was warm, bordering on humid, and as soon as we walked in, we took off our jackets. Shmoné was packed, with eager customers at the counter seats round the open kitchen from which sparks were flying. The ceiling is low; the lighting is semi-industrial; the tables are cheek by jowl. This was definitely a place to be.

By contrast, the weather on our visit to Lilienblum on a Tuesday night could not have been more ‘dreich’, as the Scots would say. It had been raining non-stop since midday. The sky was grey turning to black, made even more menacing by the very tall grey buildings that now populate this area. This London location on the ground floor of a modern building is a large, open space with an open kitchen and tables at the far end outside in a garden that must be a lovely area when the sun is shining.

Two other factors mitigate against this space. The first is that the ceiling is too high to create warmth. The second is that the lighting is too dull. It is often the case that signing a lease on a restaurant space should follow the golden rule for buying a house: see it on the worst possible day, in the worst possible light. If you still fall in love with it, then you will be happy forever.

The difference between the two restaurants’ layouts meant a significant difference in their modus operandi. At Shmoné the chef, the smiling Greenberg, was able to come to our table, to talk about which fish came from which part of the US and to spread his obvious charm (as well as show off the octopus tattooed down his right arm). Much bigger Lilienblum does not offer the same intimacy, although the service from our waiter could not have been friendlier.

We began at Shmoné with preserved lemon and za’atar and their hot bagel, above, which was useful for mopping up the sauces and olive oil that accompanied our first courses: a white aubergine steak with yoghurt; grilled leeks with ricotta; and a plate of grilled Brussels sprouts – a vegetable that seems to be on American menus the whole year round – with whipped honey.

We then shared a plate of the green garlic spaghetti before moving on to their beef short rib and a dish simply described as ‘3 Australian lamb chops, spring peas & mint salad’. The description of the short rib read ‘I promise you’ve never had one like this!’, something that was definitely true. What arrived was a large bone onto which had been placed the most professionally carved, slow-cooked pieces of meat. A treat for the eyes and the stomach.

We followed this with two desserts: an olive-oil panna cotta topped with pine nuts and more za’atar, and a slice of thick honey cake with labneh cream topped with a salty honey syrup served from a copper pot. With one cocktail, two bottles of wine and a 20% service charge the bill came to $763.71 (the equivalent of just over £600) for the four of us.

At Lilienblum we began with two mouth-watering first courses which showed considerable finesse: a plate of ‘eggplant lines’, the aubergine cut across the vegetable and topped with lashings of olive oil, and a dish of charred beetroot (purple and amber) carpaccio that followed the same principle. We then moved on to an excellent plate of hummus, with plenty of whole chickpeas on the side, all of which we mopped up with several thick slices of warm challah bread.

From the heading ‘wild fish and other creatures from the deep sea’ we chose four dishes: shrimp dumplings with sage and tomato butter; their version of hamachi sashimi, below, which was as good as Shmoné’s; what was described rather puzzlingly as calamari handkerchiefs and yoghurt; and a charred red mullet served with a fresh salad. The first three were very good. The mullet was spoilt by the fact that as it was served whole – disentangling the flesh from the bones in the subdued lighting proved tedious and not that successful.

We had brought a bottle of red wine, which the waiter readily accepted stipulating a £39 corkage charge, and we drank a bottle of Yatir’s Mt Amasa white blend from the Judean Hills that cost £85. I ordered a couple of desserts, a chocolate mousse with a salted butter cookie and a malabi (too much corn flour), which the kitchen supplemented with a sticky toffee pudding, not realising that JR hails from Cumbria, its county of origin. For this, we paid a bill of £304.88 for four including 12.5% service.

The significant difference in price highlights the biggest discrepancy between New York’s Shmoné and London’s Lilienblum. Part of that is due to the difference in the service charge: 20% as against 12.5%. But there is no escaping the inevitable conclusion: eating out in New York is an expensive pastime; eating out in London is currently less so.

Shmoné 61 West 8th Street, NY; tel +1 (646) 438-9815

Lilienblum 80 City Road, London EC1Y 2BJ, tel: +44 (0)20 8138 2847

Every Sunday, Nick writes about restaurants. To stay abreast of his reviews, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,409 featured articles

- 275,052 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,409 featured articles

- 275,052 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 48-hour preview of all scheduled articles

- Commercial use of our wine reviews